[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Jen Bervin, a poet, artist and teacher, who curated the exhibit said of Dickinson, “She was a force, an absolute force. There’s a vastness to her work that is comparable to how you might feel in an extraordinary landscape. It makes you feel very small and very humble in relation to it.”

Dickinson, who was born in Amherst, Mass. on Dec. 10, 1830 and who died there on May 15, 1886 never strayed far from home, never married and became increasingly reclusive in the last years of her life but her correspondence was voluminous and she left behind almost 1,800 poems that were discovered by her younger sister, Lavinia, after the poet’s death. Fewer than 12 of Dickinson’s poems were published in her lifetime.

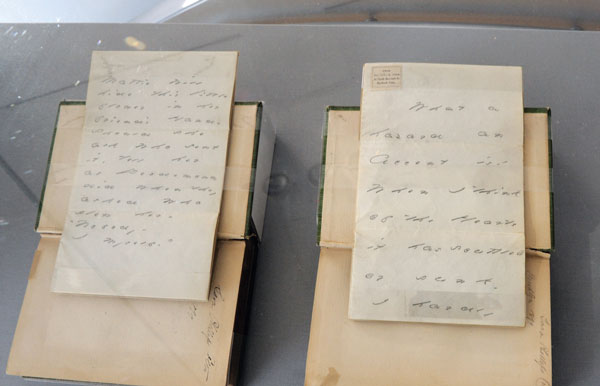

“With Dickinson, it’s quite a blurred line between a letter and a poem,” said Bervin. “A lot of her letters – and you’ll see this in the show – read just like poems. I think she never stopped thinking in poetry.”

The primary collections of Dickinson’s work are at Harvard and at Amherst College (which was founded by one of Dickinson’s grandfathers.) Donald and Patricia Oresman have one of the larger holdings of privately owned Dickinson manuscripts. They have lent their entire collection to Poets House, where many of the manuscripts are on public view for the first time. They will be there through Jan. 28, 2012.

“It’s very meaningful to me that people get to see these manuscripts in person,” said Bervin. “That’s really rare. I can’t overstate how rare that is. If you go to the archives where they have the bulk of the manuscripts, you rarely see more than this number of manuscripts. They’re not on display. You have to go as a researcher and have a very good reason to see them in any quantity and to see this many together in a public setting is really unusual.”

Dickinson’s poetry was also unusual, so much so that it would have been a rare reader among her contemporaries who could have grasped her syntaxes and the ways in which she placed letters, words and lines on a page. After her death, her first editors “corrected” her punctuation and her rhymes. It wasn’t until 1955, that versions of her poems were published that were close to what she intended, but even there, said Bervin, “In the [Thomas H.] Johnson and [Ralph] Franklin editions of her poems, all of her line breaks are changed.”

Bervin said that Dickinson’s visual sense would have made setting her poems in print difficult before the advent of modern technology. She worked throughout her life “with a very strong sense of visual composition,” Bervin said, “but in the late fragments [from 1870 to 1886], it’s absolutely stunning. The text is multi-directional. She’s composing on envelopes that are then sometimes shaped in particular ways. I don’t know of anything like them. The texts on those envelopes are pretty mind-blowing. Sometimes you see them in letters. Sometimes you see them in poems. Sometimes they exist only in that fragmentary form, but they’re just extraordinarily beautiful.”

Bervin explained that Dickinson would place “crosses” in her poems that correlated to words or phrases grouped at the end that could be substituted within the poem to create different meanings. Bervin compared Dickinson’s methods to hypertext.

“She chose not to publish,” Bervin said. “Her readers were very carefully chosen. She sent her poems in letters to specific recipients and she would send out different choices for different recipients and then in her own private draft, she might have even more choices. So it’s a very complex system. Our idea of a poem is that it’s one thing but her idea of a poem was that it seemed to be many things. She used words according to who was listening. I think it’s utterly fascinating that one of our major American poets chose to compose in this particular way.”

Bervin was inspired to make quilts depicting Dickinson’s unusual compositional method. Three of them are on exhibit at Poets House.

The late fragments, which are among the most radical of Dickinson’s writings, have been published in a book called “Open Folios” by Marta Werner, who will be giving a talk at Poets House called “Like the Wheels of Birds: Emily Dickinson’s Itinerary of Escape” on Nov. 15 at 7 p.m. It will be about Dickinson’s fragments, including canceled writings, pinned texts and envelope poems. Poets House is at 10 River Terrace in Battery Park City. It is open Tuesdays through Fridays from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. and Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.