BY MICA ROSENBERG, KRISTINA COOKE AND READE LEVINSON

Public health specialists have for months warned the U.S. government that shuffling detainees among immigration detention centers will expose people to COVID-19 and help spread the disease.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has continued the practice, saying it is taking all necessary precautions.

It turns out the health specialists were right, according to a Reuters review of court records and ICE data.

The analysis of immigration court data identified 268 transfers of detainees between detention centers in April, May and June, after hundreds in ICE custody had already tested positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

Half of the transfers Reuters identified involved detainees who were either moved from centers with COVID-19 cases to centers with no known cases, or from centers with no cases to those where the virus had spread.

The Reuters tally is likely just a small fraction of all transfers, former ICE officials said. ICE does not release data on detainee moves, and court records capture only a smattering of them.

At least one transfer resulted in a super-spreading event, according to emails from ICE and officials at a detention center in Farmville, Virginia, court documents and interviews with more than a dozen detainees at the facility.

Until that transfer, only two detainees had tested positive at the Farmville center — both immigrants transferred there in late April. They were immediately isolated and monitored and were the only known cases at the facility for more than a month, court records state.

Then on June 2, ICE relocated 74 detainees from Florida and Arizona, more than half of whom later tested positive for COVID-19. By July 16, Farmville was the detention center hardest-hit by the virus with 315 total cases, according to ICE data.

`THE WALKING DEAD’

Serafin Saragoza, a Mexican detainee at Farmville, said he and another detainee – who confirmed Saragoza’s account to Reuters – had contact with the transferees when they first arrived. His job was to distribute shoes and clothing to the new arrivals.

The new group was kept in a separate dormitory, but about two weeks after their arrival, dozens of other detainees began falling ill, 15 detainees said in interviews. The Centers for Disease Control says COVID symptoms may appear 2-14 days after exposure to the virus.

“There are people with fevers, two guys collapsed on the floor because they fainted,” Saragoza said. “There is one guy who has a really high fever. He looks like the walking dead.”

Faced with an outbreak, Farmville tested all detainees in the first few days of July. Of 359 detainees tested, 268 were positive, according to an ICE statement in response to questions from Reuters. While the majority are asymptomatic, it said, three detainees are hospitalized.

The ICE statement said the agency was committed to the welfare of all detainees and continued some transfers to reduce crowding. ICE did not respond to a request for comment on Reuters’ analysis.

Former ICE officials and immigration attorneys say the agency regularly transfers people in custody for myriad reasons, including: bed space, preparing migrants for deportation, and security reasons. With the pandemic still raging in the United States, lawmakers have called on ICE to halt the practice.

Carlos Franco-Paredes, an infectious disease doctor studying COVID-19 outbreaks in correctional settings, said it is not possible to transfer detainees safely in the current environment.

“If you’re moving people, particularly from an area where there is an ongoing outbreak, even though you sequester them for two weeks or so, there is contact with people,” said Franco-Paredes. “You’re basically spreading the problems.”

In an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19, ICE halted detention center visits in mid-March and has slowed arrests. U.S.-Mexico border crossings have also fallen, leading to smaller detained populations overall.

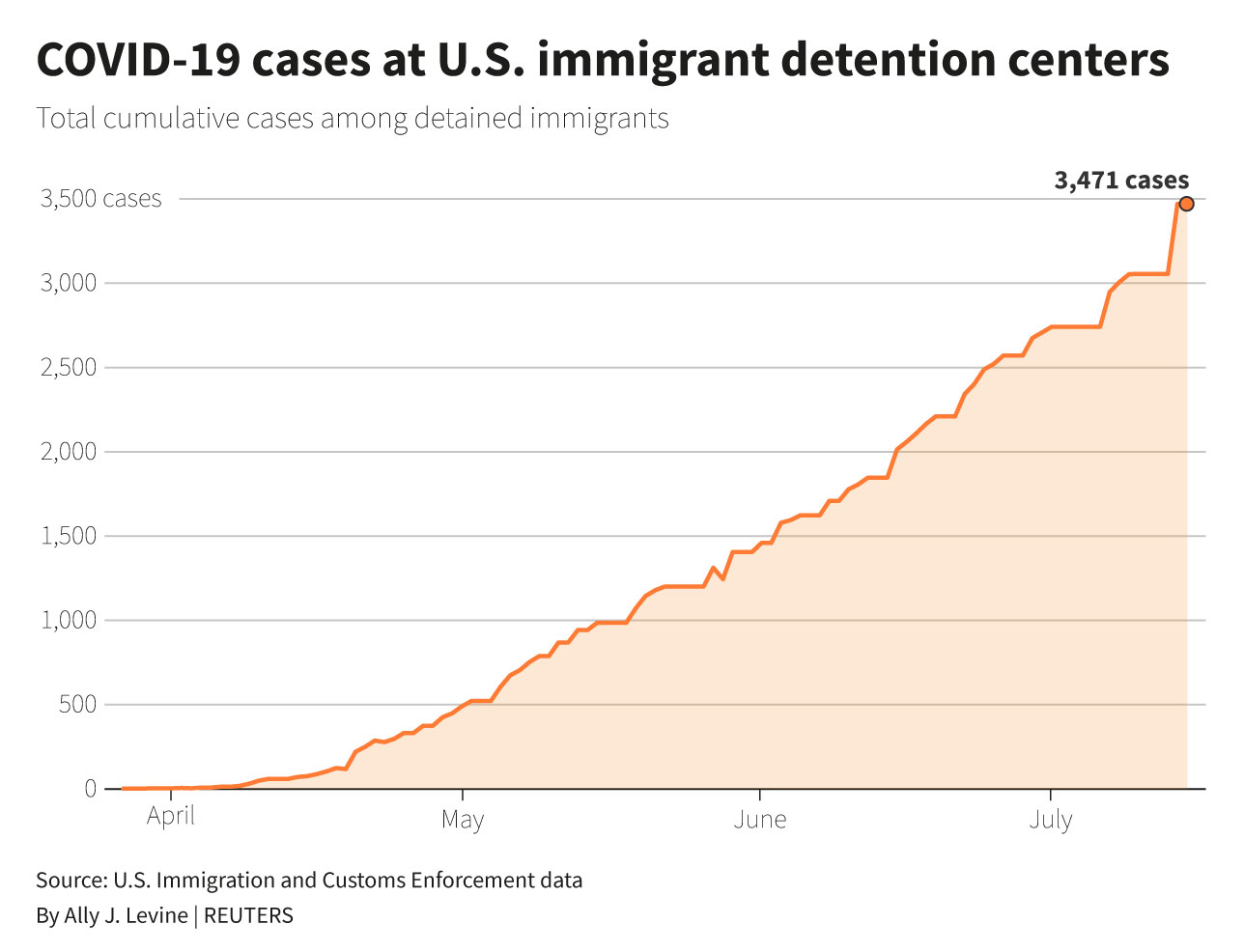

RISING CASES

Prisons and detention centers have been disproportionately affected by coronavirus outbreaks. Large numbers of people confined in close quarters with insufficient access to medical care and poor ventilation and sanitation all create a breeding ground for viral infections, infectious disease doctors say.

As of July 16, ICE had reported 3,567 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in its detention centers. The actual number of infected detainees is almost certainly higher, Franco-Paredes said, since not all centers are doing widespread testing.

About 22,000 detainees are in ICE custody now, and about 13,500 tests have been done, but that likely includes some immigrants who have since been released.

To be sure, detainee transfers are not the only means of introducing the virus to a detention center. Employees with the disease are another main source of transmission, public health specialists said. Nearly 1,000 detention center employees have tested positive for the virus.

Before it transfers detainees, ICE policy is to screen them for fevers and other symptoms, but not to test for the disease. Those with positive or suspected cases of COVID-19 are isolated from other detainees, ICE says.

MASS TRANSFER

But the case of Farmville shows that efforts to keep sick and healthy detainees separate don’t always prevent the spread.

A week after the out-of-state transferees arrived at the Farmville center, three of them tested positive for the virus while still quarantined from the general population. In response, center officials decided to test the entire group of new arrivals, according to an email from ICE deputy field office director Matthew Munroe to immigration attorneys. Fifty-one tested positive.

ICE data shows that the day before the transfers, two of the three centers where the detainees came from had reported cases. ICE’s Krome North Service Processing Center in Florida had 15 confirmed COVID cases, and Eloy Detention Center in Eloy, Arizona had one.

The Reuters review of immigration court records identified 195 transfers to or from detention centers where ICE had reported confirmed cases. These include:

–A May 6 transfer from New Mexico’s Otero County Processing Center, which at the time had 10 confirmed cases, to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, which had no known cases until two weeks later on May 19.

–A transfer on May 7 from the Bluebonnet Detention Center in Anson, Texas, which at the time had 41 confirmed cases, to the Johnson County Jail in Dallas, which had no known cases until May 19.

–Four transfers in late May from a detention center in Glades County, Florida, which at the time had no known cases, to the Broward Transitional Center in Pompano Beach, Florida, which at the time had 19 known cases.

Immigration court data notes when the government notifies the court that it has moved a detainee in its custody to another location. Reuters only counted transfers if the data showed a detainee having a hearing in a new, known detention facility, prison or jail. The news agency then compared those records to ICE counts of infections at detention centers.

Saragoza, the Mexican detainee in Farmville, lived in the United States for 21 years before his arrest. He has diabetes and high blood pressure – two conditions that the CDC says puts coronavirus patients at higher risk of falling seriously ill. He said he started feeling ill in late June but was not as sick as some others in his dormitory.

On July 9, he got bad news. He and almost all the men in his dorm had tested positive for coronavirus.