Could video games help mitigate a crisis? A Texas-based nonprofit believes so, as it aims to improve pathogen-based disaster planning through digital play, a surprising method of emergency preparedness.

The Center for Advanced Preparedness and Threat Response Simulation (CAPTRS), founded last year, has a portfolio of research-based table-top games designed to improve disaster preparedness. Its newest one, launching soon, is the organization’s first digital game. It will focus on pathogen-based disasters, similar to COVID-19.

In a post-COVID world, a game such as this, that provides scenario-based training, is necessary, explained Sarah Jane Gillett, senior vice president at CAPTRS. The game, which does not have an official name yet, will give players practice in making decisions, coordinating responses and taking action in the event of a real emergency or disaster.

“CAPTRS itself was founded so that decision makers like public health people, healthcare professionals, scientists and elected officials can prepare for global threats through simulation gaming that is based in scientific research,” Gillett said. “This game is just one piece of what we are working on right now.”

How does it work?

Here is the game scenario: Players get snippets of information about a pathogen occurring in a fictional location. The idea is to figure out what is happening, who is disseminating the information, who their credible sources are and what the plan of action should be.

The scenarios are based on real information gathered from consultations with actual epidemiologists and public health experts.

“It’s a situation that they could face,” Gillett said.

While the game is interactive, it is not player versus player. It is also a way for people around the world to play it, anywhere and any time.

“This was a logical next step in development,” Gillett said. “Something that people can individually access all over the world. It provides a way to play the game without having a facilitator present and in person.”

Using the game in New York

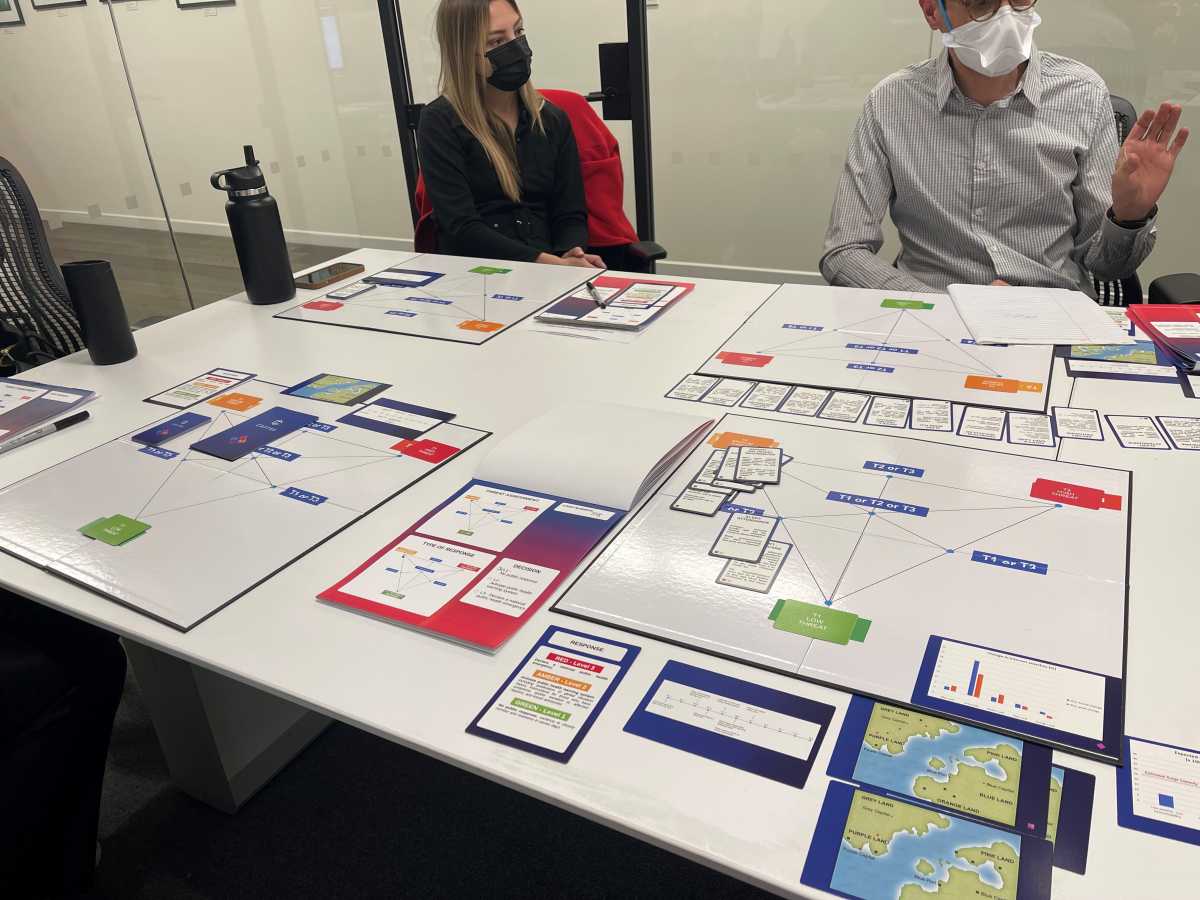

Before the game’s launch, CAPTRS recently conducted a demo with a small test group from the New York Academy of Sciences.

Mila Rosenthal is the executive director of the International Science Reserve at the New York Academy of Sciences. The reserve, which is a new initiative of the academy, is a network of scientists with different professional backgrounds who want to be on the front lines of handling specific global crises, if or when they occur.

Demoing CAPTRS’ new game seemed like a fitting idea, given the organization’s mission. A small group of about eight staff members from Rosenthal’s team played an hour-long demo, which was a maritime version of the game where players had to respond to a crisis of a ship possibly having an accident at sea.

The demo allowed scientists to test how the game would be played, how they would make decisions, check source reliability and other factors necessary to real-life disaster preparedness.

“During every stage of the game, you’re confronted with a decision to be made,” Rosenthal explained. “You get a piece of information and decide whether the source of information is reliable, and what would you do as a result.”

Do people need food? Or shelter? Can people go back to their houses tomorrow? These are only a few problems players will face when they play the game.

In essence, the game gives scientists practice in emergency management, simulating drills in a digital way and replicating what would happen in real life. It takes players through different stages of response, from what to do immediately, as well as what to do following the disaster.

“This is where a lot of the scientific and technical input comes, around all that decision making, a lot which has to be made really quickly, and is often almost being made in real time. This helps to replicate that experience when first you have very little information when you’re trying to decide how to move forward. Then you have more information as you play the second round and third round.”

Unlike most video games, there is no way to “win” this one. Rather, it gives scientists an opportunity to share their decisions and findings with others.

Rosenthal said she is looking forward to playing the pathogen-based game with other scientists in the International Science Reserve.

“It’s thrilling to imagine that we’re going to have scientists from around the world who are going to be able to play this,” Rosenthal said.