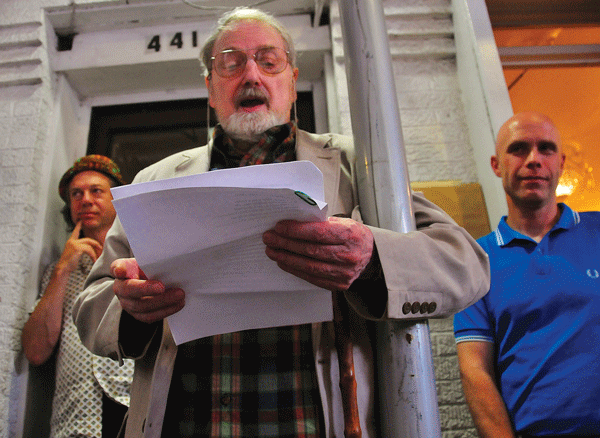

BY HEATHER DUBIN | Preservationists, poets and a pizzeria teamed up to honor Frank O’Hara with a plaque dedication at his former East Village home.

The embossed bronze homage was unveiled June 10 at 441 E. Ninth St., where the poet lived from 1959 to 1963 with his roommate, Joe LeSueur.

The ceremony was a joint effort of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, Two Boots Pizza and the Poetry Project.

Some of O’Hara’s poems feature East Village references in their titles, such as,“Avenue A” and “Second Avenue.” In “The Day Lady Died,” he mentions the Five Spot, an East Village jazz club of the 1950s and ’60s. “Early on Sunday” has a mention of St. Brigid’s Church on Avenue B.

Born in Baltimore in 1926, O’Hara grew up in Grafton, Massachusetts, and made his way to New York, where he worked at the Museum of Modern Art. He began as a clerk at MoMA’s information desk, and later, with no formal training, became a curator.

He was a part of the New York School of painters and writers — who have been called “the last avant garde” — and hung out with them at the San Remo Café on MacDougal St. and at the Cedar Tavern on University Place.

“Frank was a groundbreaker in so many ways, which is reflected in his poetry,” said Andrew Berman, G.V.S.H.P. executive director. “He was openly gay at a time when that was not so easy, and he wrote about his sexuality with an ease and casualness that was rare at the time.”

During his lunch hours at MoMA, O’Hara penned several poems that contributed to his collection “Lunch Poems.” There is an immediacy and journal-entry-like quality to his work, which creates a feeling of accessibility.

A fiftieth anniversary of “Lunch Poems” was reissued by City Lights books, and a reading of O’Hara’s poems was held June 11 at the Poetry Project, at St. Mark’s Church.

O’Hara died at age 40 during the summer of 1966 on Fire Island.

“What he wrote lives in the hearts and minds of so many people here today,” Berman said.

Phil Hartman, owner of Two Boots Pizza since 1987, has been funding G.V.S.H.P.’s historic plaque program through the Two Boots Foundation. The plaque program aims to preserve the Village’s history, and remember people who have made significant contributions to the neighborhood.

“Honoring great artists from the past is an important mission for us,” Hartman said.

Edmund Berrigan read O’Hara’s “Avenue A” aloud. The Brooklyn poet recalled growing up around the corner on St. Mark’s Place and First Ave.

“What this neighborhood is about has drifted away as I’ve gotten older,” said Berrigan, 39.

Berrigan is the son of poets, Alice Notley and the late Ted Berrigan, who were friends with O’Hara. Ted Berrigan founded C magazine, and also had a publishing relationship with O’Hara.

“My dad was a champion of his poetry,” Berrigan said of O’Hara, “He was one of many advocates.”

Berrigan’s parents quoted O’Hara at home and had his books. When deciding which poem to read at the dedication, Berrigan consulted his mother.

“She suggested I read ‘Avenue A,’” he said. “She told me I’d cry when I read it — I didn’t.”

Despite his pedigree, Berrigan wasn’t pressured to become a poet. He remembered writing in collaboration with his mom.

“I don’t know if I expressed an interest in it, but at age 8 I was given a blank book,” he recalled. “I wrote poems in it, and I’ve never really stopped.”

Poet Tony Towle read O’Hara’s “The Day Lady Died” at the plaque event. Towle was friends with O’Hara, and the E. Ninth St. apartment was passed on to him and Joe Lima after O’Hara moved out.

“When Frank was here, the place had charm,” he said. “A Motherwell and a de Kooning and other artwork on the walls, the interesting books on the shelves, the bourbon in the glass, the Prokofiev on the record player, and, above all, his engaging conversation.”

When Towle lived there the rent was $56, and he and Lima would buy kielbasa, bread, milk and eggs on credit from the deli across the street, just like O’Hara and LeSueur did.

O’Hara’s time on E. Ninth, Towle noted, was a prolific period for the influential poet.

“He wrote everything that ended up in ‘Lunch Poems’ [except for the book’s last poem], and what was included in ‘Love Poems (tentative Title),’ that he wrote for Vincent Warren, and also the unique ‘Biotherm,’ ” he said.

Towle acknowledged that O’Hara was able to write no matter what his environment.

“He just ignored it, if it was hot or cold — something I can’t always do,” Towle said.

“He typed his poems on the kitchen table, up there on the second floor between the first and second window, accompanied periodically by the din of the Ninth St. crosstown bus,” he added.

A second dedication of a historic plaque for another artist is anticipated for this fall.

“There’s so much history in these neighborhoods,” Berman said. “It’s not always apparent to people. This is a way to memorialize it and preserve it in a tangible way.”

According to the preservationist, the task is not easy. He sends lots of requests to building owners just to secure one positive response. And then there is the issue of finding an appropriate physical space to attach a plaque.

“There are a lot of stars that have to align to make this work,” he noted. “It’s a lot more work than it looks like.” But, he said, “It’s worth it.”

Removing a new plaque’s covering at its unveiling is something Berman cherishes.

“I always love that moment when I take that stuff off,” he said, “and introduce it to the world.”