BY NORMAN BORDEN | There are many breeds of fine art photographers, but William Wegman has long had a pedigree all his own. He has been photographing dogs — not just any dogs, but his beloved Weimaraners — for nearly 40 years. With Man Ray as his first muse, Wegman has humanized his dogs to the point of absurdity at times and made them famous.

Long recognized as a brilliant conceptual artist, painter, photographer, writer, and video artist, he has portrayed his dogs as landscapes, put clothes on their backs and everything from wigs to fruits on their heads, thereby making us take a closer look at ourselves. With a wink here and there, he has turned his dogs into a cast of whimsical characters, virtually guaranteed to make us smile while we wonder how he does it.

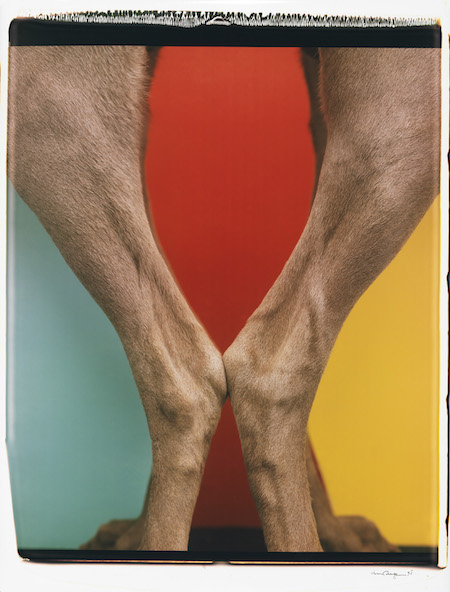

More smiles are in store in “William Wegman Dressed and Undressed,” a thoroughly engaging show at Sperone Westwater of 20 x 24 inch Polaroids never exhibited before. It spans over 30 years of Wegman’s Polaroid work and, amongst its many charms, it challenges the viewer with visual sleight of hand. Is that a mountain range or a dog’s back? Is that a wine glass or dogs’ legs artfully composed? Why is one dog much bigger than the other? It’s Wegman’s well-known wit at work.

Speaking recently with this publication by phone, the artist explained how Man Ray started it all. “I got him in September 1970 as a very young puppy.” Wegman recalled. “I had just started to do video and photography so I took him to my studio and took his picture. Naturally, if you have a baby, you take his picture and it was sort of magical the way he looked on camera. I was working in black and white photography and video and he was grey; somehow he seemed to suit it. The longer we worked, the more involved it became and the more hilarious he was, especially in video.”

In 1979, the Polaroid Corporation invited the artist to try out its new 20 x 24 inch camera. He took Man Ray to Polaroid’s Boston studio to work with him and liked the large format and the almost instantaneous (70 seconds) exposure. “I reveled in that everything was the same 20 x 24 vertical,” Wegman said. “I loved that. I didn’t have to think how big this should be. Polaroid was great because you could see every little trick. If you tried to hide something, forget it, you couldn’t Photoshop it out. The dogs were really cooperating; they weren’t just stuck in there in some post-production way. That’s what I liked.”

However, the camera had its limitations. It was huge, weighing over 200 pounds — and since it couldn’t be pointed down at the ground, Wegman used special stools and pedestals to raise the dogs up to camera height. In the studio, if the shot he was trying to get didn’t work out after two or three exposures, he said, “I’d stop and go another way… It sticks its thumb out at you. It costs a lot of money to make and gives you this tremendous energy to correct it.”

After Man Ray died in 1982, Wegman didn’t get another dog until 1986 when Fay Ray entered the picture. “The real laughs came with Fay Ray,” the artist recalled. He took hundreds of Polaroid images of her and her offspring until 2007, when Polaroid stopped making the 20 x 24 film. He would rent the 20 x 24 camera every couple of weeks and take 4 x 5 inch color transparencies of a few Polaroids for exhibitions, and store the rest in archival boxes. “I would never look at them again,” he said. But when writer Bill Ewing proposed doing “William Wegman: Being Human” (published Oct. 3 by Thames & Hudson), these archived Polaroids became the basis of the book and the current show. Ewing, the artist noted, “is the one who broke down these characters into chapters like ‘Landscapes’ for the book and ‘Dressed and Undressed’ for the show. I thought it was funny having nude dogs and characters. I never thought of myself as the guy who dressed up all the dogs, but most people probably think that.”

Asked his reaction when Polaroid announced it was ending 20 x 24 film production, Wegman’s answer was surprising: “I was kind of relieved. The camera was exhausting to use.” Of course, at that time, digital photography was changing everything. According to the artist, “Digital is way more instantaneous… The choices you can make are huge — how many, how big, how little, do you add something, subtract something?”

One of the more riveting images in the show is “Parcheesi.” Composed of two dog legs touching each other; the negative space looks like a wine glass. It’s just amazing. “Parcheesi looks easy,” Wegman said, “but it was very hard to do… everything had to be just so… It’s very geometric; a map of dog legs, ‘Parcheesi’ [a classic board game] refers to the colors.”

When asked how he gets the dogs to pose, Wegman replied, “The dogs are so calm. Once they get in the studio they let you adorn them. They like the attention, they like being looked at, held, talked to and used. They thrive on the interaction. They’re calm around me, but not other people. Must be something I do. They’re always looking at me like, what should we be doing, Bill?”

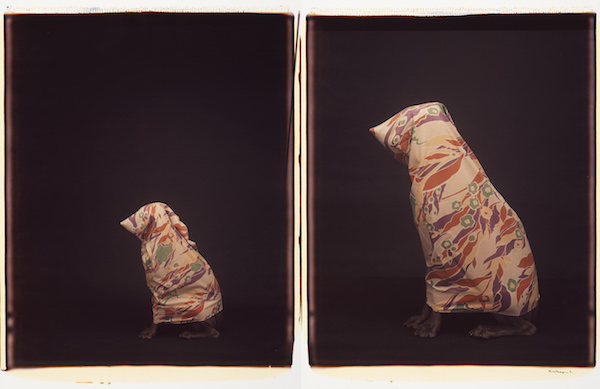

In viewing the diptych “Victor/Chundo,” which features a ceramic statue of the iconic RCA Victor — its head tilted to the right and Chundo, the number one son of Fay Ray, tilting his head to the left — one has to wonder, how did that happen? ”You can elicit the tilted head by speaking sweetly,” Wegman explained of his method of questioning. “Do you want to go for a walk or be in a video? They’re trying to listen and hear what you’re saying.”

In the photograph “BATTY/Batty,” size matters. The conceit here is that the small image is actually a cutout from a Polaroid. The artist revealed that he made a little stand for the small picture and after placing it next to Battina, took the Polaroid of the photo. Very clever.

In “Daisy Nut Cake,” an incredible parody of Renaissance painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s work, Fay Ray sports two Slinkys with glass eyes, her head covered by fruit, flowers, and a hat. Wegman said, “Fay had remarkable steadiness and willingness to put up with this stuff. Fay was proud of her stamina.”

So where does this conceptual genius get his ideas? Wegman credited the source as the dogs themselves. “Some of the later ones, where I turned them into landscapes, came from looking at my groups of dogs lying on the couch close together, creating hills and valleys… and probably a lifetime of working with them in the studio, playing with them, and living with them in your house gives you ideas. Once in a while there’s a project, like when the Metropolitan Opera loans you sets and costumes and asks, ‘What can you do with that?’ Once I became well-known, it’s kind of thrown in your lap and ideas come from that.”

Through Oct. 28 at Sperone Westwater (257 Bowery, btw. Houston & Stanton Sts.). Hours: Tues.–Sat., 10am–6pm. Call 212-999-7737 or visit speronewestwater.com. Artist info at williamwegman.com.