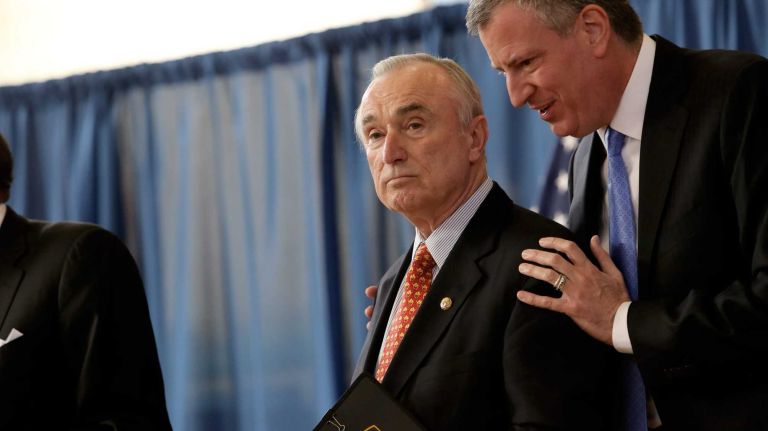

There are two ways to regard last week’s joint announcement by Mayor Bill de Blasio and Police Commissioner Bill Bratton that the city would drop its appeal of federal judge Shira Scheindlin’s ruling to end Stop and Frisk.

The first is to recognize this as a moment of good feeling in the first month of a new administration, and to accept at face value their seconding Scheindlin’s description of Stop and Frisk as “indirect racial profiling” and “deliberate indifference” by former police commissioner Ray Kelly and former mayor Michael Bloomberg.

The second is to regard de Blasio’s and Bratton’s posturing over Stop and Frisk as a brilliant yet cynical attempt to exploit a policy whose abuses had largely ended last year, when Kelly reduced the number of stops in the third quarter of 2013 to 21,000 — from 100,000 stops during the same period in 2012.

By then, 12 years into his reign as commissioner, Bloomberg had lost control of Kelly and Kelly had lost control of himself.

His ego had become so inflamed that he refused to acknowledge that the reduction in numbers amounted to a change in policy. Acknowledging this would have indicated his unchecked Stop and Frisk practices had been flawed.

To determine how serious de Blasio and Bratton are about ending racial profiling, let’s see what they do about releasing documents describing the police department’s pervasive spying on the city’s Muslim communities, which went also unchecked under Kelly and Bloomberg [and produced virtually nothing in the way of capturing terrorists.]

Last week a federal judge ruled that the city must turn over documents for his review to determine whether he should turn them over to the Muslim plaintiffs.

“Even so neutral and apolitical an individual as a federal judge may be permitted to wonder whether these changes on the thrones and in the corridors of municipal power may have an effect upon the resolution of disputes as this class action …” Judge Charles Haight wrote in his bloviated manner.

So far neither de Blasio nor Bratton has spoken on this subject.

As for Stop and Frisk, no one can contest that there has been a dramatic 20-year decline in crime in New York, in which — [the hysteria in the Post and the Daily News to the contrary] — Stop and Frisk does not appear to have played a significant part.

That dramatic decline, we can say categorically, began in 1994 when Rudy Giuliani became mayor and appointed Bratton police commissioner.

Kelly — then police commissioner under David Dinkins and in the midst of his “community policing” outreach, largely to the city’s black communities — responded by saying of Giuliani’s and Bratton’s aggressive crime-fighting tactics: “It goes to the kind of policing we want in America. You can probably shut down just about all crime if you’re willing to burn down the village to save it. Eventually I think there will be a backlash and crime will go back up.”

How ironical that statement sounds today. As de Blasio and Bratton announced the end of the Stop and Frisk appeal, Kelly appeared the heavy and Bratton the white knight, who stated heroically: “We will not break the law to enforce the law.”

Meanwhile, a complimentary editorial in the NY Times rewrote some city history,stating that Bratton had “made community relations a cornerstone of his career.”

Fact: Under Giuliani, the two of them ridiculed community policing as “social work.”

Wherever this cornerstone of Bratton’s career was laid, it was not in New York City.

Finally, let’s turn to the fears of some that de Blasio, who held a minor position in the Dinkins administration, would return the city to that crime-filled past.

First, there are stark differences between de Blasio and Dinkins. Whereas Dinkins seemed distracted, almost lazy, de Blasio seems like a hands-on guy.

Second, Dinkins’s primary police commissioner, Lee Brown, who led the department from Dinkins’s inaugural in 1990 through the summer of 1992, was arguably the poorest in the city’s modern history.

An outsider to New York, he never got his hands around the NYPD. Nor did he grasp the seriousness of the Crown Heights riots, which began after a city-sanctioned Hasidic motorcade caused an accident that led to the death of an eight-year-old black child, and culminated with the fatal stabbing of a Jewish rabbinical student by a black mob.

Bratton may know how to posture, but he also knows New York. More important, he knows policing.

Returning to the city with a supportive mayor and with some lofty language about cleaning up Stop and Frisk, he begins in what seems a no-lose situation.

But in another sense, he’s in a situation in which he can’t win.

Besides dramatically reducing crime, Giuliani made crime a daily political issue. Already, the Post has cited as a warning a 33 per cent “spike” in homicides during January.

Should this continue, guess who’ll be blamed?

Let’s see what Bratton and de Blasio will then be saying about Stop and Frisk.