Despite making up a mere 4 percent of the world’s population, the United States accounts for 80 percent of all opioid consumption worldwide. The nation is in the midst of a startling epidemic of opioid abuse – and Manhattan is in no way exempt from it.

For this reason, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer (D) decided to organize a seminar on opioid addiction awareness.

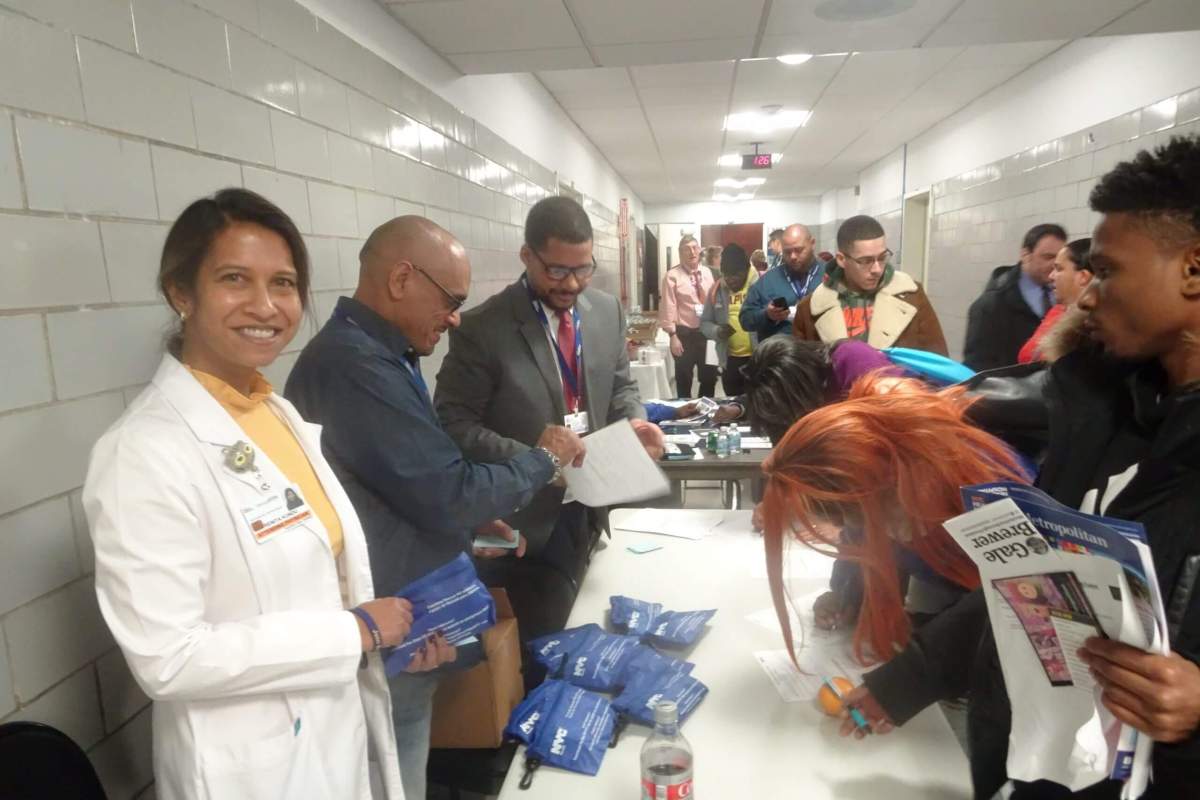

The seminar took place on Friday, Dec. 13 at 12 p.m. at Metropolitan Hospital, 1901 First Ave. Brewer specifically chose to host the seminar in East Harlem, the neighborhood with the highest rate of opioid overdose deaths in Manhattan. Accompanying Brewer were Metropolitan Hospital Chief of Psychiatry Ronnie Swift and Herbert Quinones, overdose prevention trainer at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Ronnie Swift began by providing an overview of what an opioid is and the scope of the opioid addiction epidemic. The term “opioid” refers to a class of drugs used to relieve pain and invoke pleasure. Examples include morphine, heroin and oxycontin.

As of now, one of the most popular opioids on the market is fentanyl, a synthetic compound with 30 to 50 times the potency of heroin. By 2016, fentanyl was present in almost half of opioid overdose deaths in New York City. As Swift explained, dealers will often use the compound as “fillers” for other drugs, such as cocaine and Xanax. Since fentanyl is invisible, tasteless and odorless, there’s no way to tell if a drug sample has fentanyl in it.

“They’re using it as fillers for these drugs, so they look bulkier to the person who’s getting the white powder,” said Swift. “But the minimum lethal dosage of fentanyl is tiny.”

Swift also pointed out that opioid addiction is a disease that can affect anyone – regardless of their socioeconomic status or moral character.

“I know someone who started using opioids for his back pain after a very serious car accident,” said Swift. “He used them for years, but then he could never get off of them. He got his meds via mail, so he spent every day by the mailbox waiting for the mailman. And that’s when he realized he had a substance abuse problem. It didn’t strike him how dependent he had become, because it happened so gradually.”

Next, we heard from Gale Brewer, who recounted her own experiences growing up in a neighborhood plagued by rampant drug abuse. She spent twenty years living on 82nd and Amsterdam, in the midst of the crack cocaine epidemic. She and her husband were a certified foster-care family, and were responsible for fostering 35 children.

“For those twenty years, a lot of people came to live with us because their parents were in drug treatment,” said Brewer. “People in every part of our community were exposed to crack. And now in 2019, we are contending with a drug that’s even more of a killer.”

Finally, Herbert Quinones taught the audience how to recognize and treat an opioid overdose. The most common signs of an overdose are visible drowsiness, unresponsiveness and slow breathing. If you see someone exhibiting those symptoms, you should first try to elicit a reaction from them. Quinones recommended shouting their name, and then performing a “sternal rub”, which involves grinding your knuckle against their breastbone.

“You’re walking down the street, and you see somebody unconscious – not breathing, blue and grey lips,” said Quinones. “What’s the first thing you’re gonna do? Shout at them. Try to get a response from them. If they wake up, they’re not overdosing. That’s why this step is important.”

If the victim is still unresponsive after both of those tests, you must first call 911 for medical assistance, and then administer treatment. The most common and effective way to treat an opioid overdose is with the drug naloxone, which is specifically designed to reverse the overdose’s effects. Quinones pointed out that naloxone has no adverse side effects, even if it’s taken by someone who doesn’t need it.

“Administer the naloxone,” said Quinones. “If they took an opioid, you’ll save their life. If they didn’t, you’re not going to hurt them. When in doubt, administer the naloxone.”

At the conclusion of the seminar, each of the attendees received a free naloxone kit to take home.