Inequality is hazardous to New York City’s health.

That’s the finding a new report from advocacy group Transportation Alternatives which declared that New York City’s public space is distributed highly inequitably on racial, ethnic, and income-based lines, a phenomenon leading to alarming disparities in health, environmental quality, and public safety.

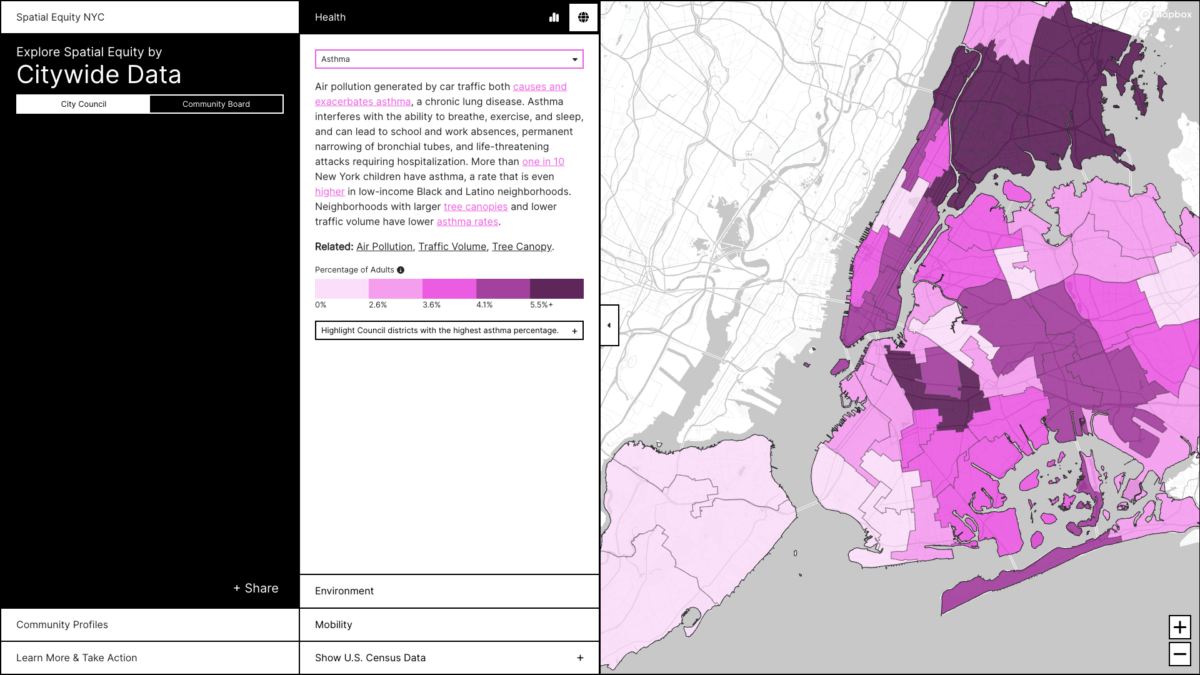

The report, created in conjunction with Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, includes a new online tool called Spatial Equity NYC analyzing publicly available data, found apparent connections between a lack of non-automotive public space and poor public health outcomes, like high rates of asthma or traffic injuries.

The most aggrieved areas were also disproportionately low-income and/or communities of color.

“This is why how we think about public space is so critical. How our streets, our sidewalks, and our green spaces are distributed,” said Elizabeth Adams, advocacy director at Transportation Alternatives, during a rally at City Hall on Tuesday. “In order to make our city work for all of us, we have to be clear about the ways that our public space has not worked for far too many New Yorkers for far too long. Decades of planning and policies have led to severe environmental and public health abuses of Black and brown communities across our city.”

While most of the city’s public road space is devoted to the movement of the automobile, certain communities have benefitted from conversions of public space more than others. The report found that majority-white City Council districts have protected bike lanes on 6% of streets, compared to 1% for majority-Black areas and 2% for majority-Latino nabes. The district with the most protected bike lanes, District 3 on the west side of Manhattan, actually has more protected bike lanes than the bottom 23 districts combined.

The most nonwhite districts have 83% fewer protected bike lanes, 64% fewer bike parking spaces, 57% fewer bus lanes, and 58% more traffic deaths than the whitest districts, according to the report.

One can draw a straight line between those statistics and disparate rates of traffic injuries, the report’s authors say. In the 10 districts with the most traffic injuries, 87% of residents are people of color compared to 67% citywide. Those 10 districts also have 42% fewer protected bike lanes than the citywide average, the authors notes.

The neighborhoods with the most bus lanes and busways are disproportionately white, while the neighborhoods with the least park access are disproportionately Black.

That baked-in inequity leads to problems downstream that become harder to address as time goes on. The districts with the highest asthma rates are also disproportionately communities of color. The districts with the highest average daytime temperatures are also disproportionately nonwhite, while the districts with the most car traffic and slowest buses bear high levels of air pollution.

Disparities are seen not just along racial lines, but income lines as well. The districts with the highest proportion of residents living below the poverty line have higher rates of asthma, slower buses, and fewer protected bike lanes, per the report.

Asthma rates are particularly stark in the Bronx, surface temperatures are disproportionately high in eastern Queens, and Staten Islanders suffer from the worst access to parks.

“What this does is gives us a bird’s eye view of what’s going on. It gives us a bird’s eye view of inequity that cannot be ignored,” said Public Advocate Jumaane Williams at the rally. “It goes from past anecdotes to actual facts and information that our leaders can use to make better policies, or rather our leaders should use to make better policies. There’s no way you should have this kind of information and keep doing the same old thing we’ve been doing.”

The website, whose underlying metrics come from the city’s Open Data and US Census demographics, and is intended to be used as a research tool and to back issue campaigns with hard data and analysis. Transportation Alternatives on Tuesday also launched a petition to call on city government to commit to their goal of converting 25% of the city’s car-dedicated area into “space for people” by 2025.