Power, in the eighteenth century, was never subtle — it was staged, dressed, and painted into permanence. At The Frick Collection, Gainsborough: The Fashion of Portraiture restores that truth with operatic force, placing Thomas Gainsborough back into the charged social theater that produced him.

It was a world where lineage behaved like law, clothing operated as rhetoric, and a painted likeness could secure a family’s place in cultural memory longer than any title deed.

This is New York’s first exhibition devoted to Gainsborough’s portraiture, and it reads less like a survey than a revelation. Status, in Georgian Britain, was not casual. It was constructed, defended, and performed. Family name functioned as architecture. Fabric functioned as argument. A portrait was not decoration; it was social strategy rendered in oil.

One commissioned canvas could stabilize reputation, advertise virtue, and broadcast wealth across generations. Gainsborough understood this machinery intimately, even as he complicated it personally — marrying for love rather than rank, choosing Margaret Burr, widely believed to have been the illegitimate daughter of a nobleman, in quiet defiance of the very pedigree logic his patrons worshipped. The painter of aristocratic image did not fully submit to aristocratic rules, and that paradox gives the work an added voltage.

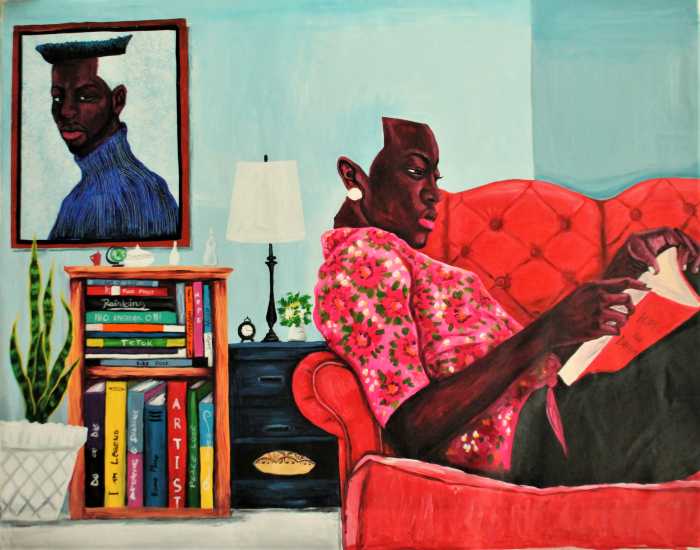

What makes these paintings astonishing is not merely who is depicted, but how.

Gainsborough’s technical language feels airborne. The brush moves with a wispy, elastic intelligence — gliding, lifting, dissolving — so that fabric appears to shift even now under changing light. Satin does not sit flat on the body; it turns, catches, exhales. Lace trembles into existence through broken highlights and feathered touches. Velvet absorbs shadow like pooled dusk.

His surfaces are built through translucent veils and loaded strokes that taper at the edge, allowing air to circulate through the figure. Stand close and the marks feel almost abstract — slashes, flickers, vapor — then step back and the storm resolves into composure, rank, and breathtaking fashion. It is alchemy by distance.

Fashion is the true co-author of these portraits. Silk gowns surge like weather systems. Organza and gauze dissolve at the edges into pure light. Embroidery is suggested through pricked highlights and quick jeweled taps of pigment. Powdered hair rises like sculpted cloud. Sashes cut diagonals of authority across the body. Military coats, riding habits, opera dress, pastoral costume, and aristocratic black each signal a different social script.

Gainsborough paints textiles not as static description but as performance — garments mid-movement, sleeves turning, ribbons loosening, capes breathing. Within this theater of dress, there are elegant nods to Anthony van Dyck — in the cascading drapery, the elongated line, the aristocratic sweep — yet the emphasis remains on contemporary fashion as living language, not historical quotation. Style becomes signal. Fabric becomes psychology.

The famed conversation pieces expand the drama further, allowing Gainsborough to weave his beloved landscapes into the portrait field so that sitters inhabit weather rather than wallpaper. Trees lean into the composition. Skies participate. Social identity unfolds inside the environment, not against the backdrop. Even when he complained about the “Face Business,” he elevated it, loosening the pose and softening the hierarchy so that relational life could enter the frame.

Then the exhibition delivers its most piercing and modern note through the portrait of Ignatius Sancho, and the centuries collapse into the present tense.

Sancho — born into enslavement, later a composer, writer, and major Afro-British intellectual — is painted with unmistakable regality and interior authority. He appears not in a servant’s livery but dressed as a gentleman, with composure and intelligence emanating through the handling of the face and the dignity of presentation. The paint does not diminish him. The paint confers presence.

In a century we too easily label as irredeemably distant, here stands an image that answers directly to our present conversations about representation, marginalization, and the long fight for unadorned human dignity. The marginalized have always fought to be seen not as symbols and not as functions, but as fully realized individuals. Sancho receives that gravity here, and the effect is quietly radical.

The exhibition also reveals Gainsborough as a restless reviser who returned to canvases to adjust costumes, update styles, and recalibrate impressions as fashion and circumstance evolved. Identity, even then, was not fixed. It was negotiated, retouched, and refined. Paint became a living instrument of time.

Everything in this show breathes — the textiles, the flesh, the atmosphere, the ambition. The cumulative effect is sumptuous, historically grounded, and technically intoxicating, reminding us that fashion in paint is never trivial. It is biography, politics, aspiration, and illusion fused into the surface.

See it in person and give the work the time it demands at frick.org.