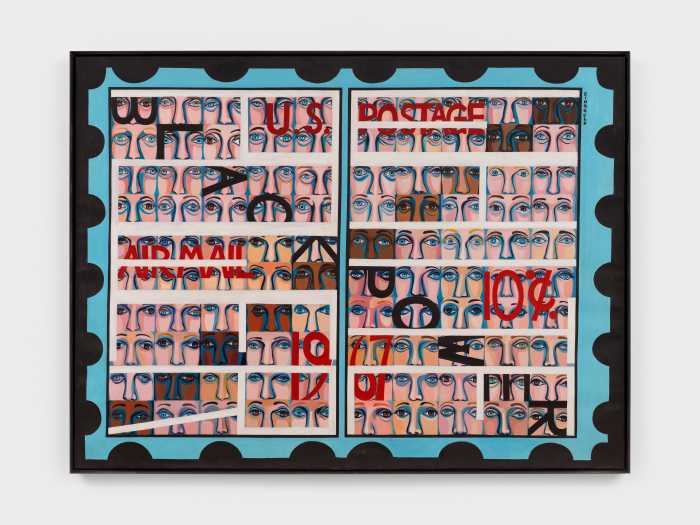

Turning a corner on the fourth floor at the Museum of Modern Art, it appeared: “Dogs of Cythera” by Dorothea Tanning. Suddenly, the tempo of my visit collapsed — not into calm, but into excited consequence.

I had moved through the museum at a near run — heels striking the floor, senses thrown open — still electrified by Wilfredo Lam, but unsatisfied. It was that familiar MoMA condition: the body outrunning thought, the eye consuming faster than meaning can form. Room after room, sensation skimmed the surface, failed to anchor, slipped away.

Then something curious asserted itself. The works that halted me did so before identity entered the exchange. Impact first. Then stillness. Authorship only afterward. Each time I looked to the wall, the discovery repeated itself—not as agenda, but as fact. The work of that mandated my attention were all by women artists.

There is an irony in that realization, faint but undeniable, given how recently such work was permitted sustained visibility within institutions of this scale. History hesitates. Perception, when left unprompted, does not.

Then came “Dogs of Cythera.” This particular consequence sharpens when one pauses—truly pauses—to register the conditions in which this artist lived.

One must admit, it is quietly astonishing to recognize how recently a woman’s autonomy was conditional: permission threaded through the most ordinary gestures of adulthood. To accept employment. To travel unaccompanied. To spend one’s own money without justification or intermediary. Even a credit card could not be issued to a woman until 1974, a date proximate enough to disturb any belief that such constraints belong to a sealed past.

What emerges is not outrage, but a more cerebral unease—the understanding that obedience once functioned as infrastructure, that silence passed for refinement, that ambition carried a faint yet persistent trace of impropriety. These were not spectacular prohibitions, but ambient rules, imbibed and normalized through daily repetition.

Tanning’s work does not dramatize this reality. Instead, it is metabolized and then released in altered form.

The pressure of those conditions becomes internal logic rather than external subject matter. Her paintings think through constraint rather than depict it, converting limitation into motion, refusal into structure. What might have required permission in life becomes, in her work, an ungovernable force—quietly, decisively, and without appeal.

Her early interiors bristle with awareness. Doors proliferate. Corridors curve. Rooms register as sentient—regulatory. Women occupy these spaces not as riddles or ornaments, but as consciousnesses in the midst of awakening. Upon viewing, one is struck with a sense of discomfort as elegance gives way to containment and normalcy turns adversarial. The paintings withhold resolution and require the viewer to remain with unease.

Then comes the pivot. Not necessarily a stylistic drift— but a decision. By the early 1960s, her figuration loosens its hold because the body, overdetermined for centuries, demands release. This is where movement assumes command and the canvas becomes event.

In 1963, Tanning and her Dogs of Cythera arrive as correction. Cythera — the Rococo dream of effortless pleasure — enters Western art history most famously through Jean-Antoine Watteau’s “Pilgrimage to Cythera,” an image of lovers drifting through a pastoral theater of sanctioned desire, where femininity functioned as ornament and leisure masked authorship. That vision—so foundational it appears on the cover of the publication you are now holding—cemented Cythera as a site of elegance without consequence.

Tanning does not quote this lineage; she ruptures it. Where Watteau lingered, she accelerates. Bodies surge rather than promenade. Limbs fragment into velocity. Color abandons description for propulsion. What was once an idyll becomes a pressure field. Beauty, here, is earned through resistance.

The work itself has absolutely no privileged vantage point. No governing gaze. It’s as if authority disperses across the surface, obliging the viewer to move with the painting rather than command it. Here abstraction is not retreat; it is expansion that whispers. Most poignantly, desire shifts from something imposed upon women to something generated through motion. Untamed. Uninhibited.

Seen now, Tanning reads less as a chapter of Surrealism than a recalibration of its assumptions. She does not announce rebellion, rather, she performs it—through motion that refuses stagnation and beauty that withholds submission. Mercifully, the viewer is not instructed. The viewer is implicated.

Dorothea Tanning understood that the most effective war is structural, dismantled from within. Her work remains agile, exacting, and dangerous—reminding us how recently obedience was demanded, how deliberately silence had to be unlearned, and how power, once set in motion, proves almost impossible to arrest.

Dogs of Cythera is on view at the Museum of Modern Art. For more information, visit moma.org.