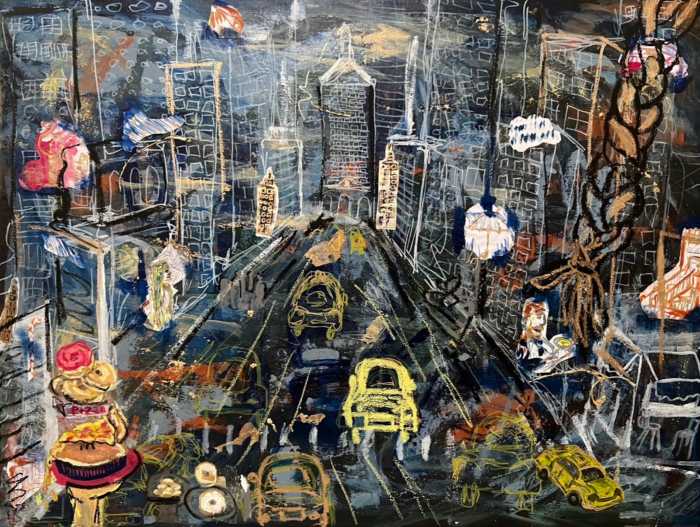

When John Singer Sargent arrived in Paris in the spring of 1874 — barely 18, impossibly gifted, and burning with aesthetic ambition — the city was still licking its wounds from war and revolution, yet already reemerging as the glittering crucible of modernity.

The Franco-Prussian War had torn the map apart. The new French Republic was grasping toward identity. And into this frayed, ferocious beauty walked a young American with a paintbrush and the gall to look Paris straight in the eye.

Sargent was no ordinary prodigy. He was multilingual, dangerously observant, and socially fluent in ways that made salons open and secrets spill. He soaked in antiquity at the Louvre and lingered over the luminosity of the Impressionists—drinking deeply from both the sacred and the subversive. But what made him unforgettable, what secured his place in the pantheon of portraiture, were the women.

Ah yes. The women.

To speak of Sargent without invoking the women who haunt his canvases is to miss the entire point. They were not muses in the soft-focus sense. They were not props, nor passive conduits for a man’s genius. These women—Madame X, Virginie Gautreau, Edith Sitwell, Carmen Dauset—were the alchemy.

They were the storm at the center of the frame. Their posture was the architecture of elegance. Their silence was deliberate. Their gaze was subversive. They elevated Sargent’s reputation precisely because they refused to be diminished by it.

Sargent painted with a kind of flamboyant restraint. He let the fabric do the talking. He understood that light, when used correctly, was not just illumination—it was seduction.

Lace became weaponry. Bare shoulders became social warfare. A single turn of the wrist could dismantle decades of decorum.

In the decade following his arrival in Paris, Sargent climbed the ladder with balletic precision, each portrait a rung, each sitter a revelation. He captured the dissonance of a changing world—a Paris where old money collided with new ideas, where the salon was both sanctuary and stage. His portraits weren’t merely likenesses; they were loaded cultural documents, whispered proclamations of who these women were and who they refused to be.

Then came Madame X.

Ah, Madame X. The scandal that sealed his legend. Painted in 1884, this portrait of Virginie Gautreau, an American expatriate known for her haunting beauty and lethal charm, was meant to be his masterpiece. It became his rebellion.

With skin like alabaster and a strap slipping ever so slightly from her shoulder, Gautreau was painted not just as a woman — but as a revolution. Paris recoiled. The critics clutched their pearls. Sargent, unbothered, fled to London. And yet the portrait endured.

Today, Madame X is one of the crown jewels of The Met. Her stillness vibrates. Her posture sneers. She is less a subject and more an exclamation point in corset and velvet.

This exhibition, tracing Sargent’s ascent in Paris during that singular decade—from his arrival through the detonation of Madame X—is more than a retrospective. It is a resurrection. It reminds us that genius is not born in a vacuum. It is born in tension, beauty, and defiance. It is born when an artist dares to render a woman not as an ornament but as an oracle.

Sargent was a master of technique. But what made him immortal was his ability to frame the unspeakable—female power—in brushstrokes too elegant to be dismissed and too daring to be ignored. The women in his portraits did not need to shout. Their silence was symphonic.

A century after his death, Sargent’s canvases still ask the most dangerous question of all: What does it mean to be seen?

And the women he painted? They answered with a gaze that still burns through the canvas.