There are moments in history when beauty becomes a form of defiance. Renoir was born into such a moment.

In a century accelerating toward mechanization and grinding industrial routine, he chose to illuminate tenderness. While cities were carved by new boulevards, governments reshaped identity, and the pace of daily life tightened into something metallic and swift, he devoted himself to the warmth of bodies, the softness of touch, the intimacy of afternoons where nothing was demanded except presence.

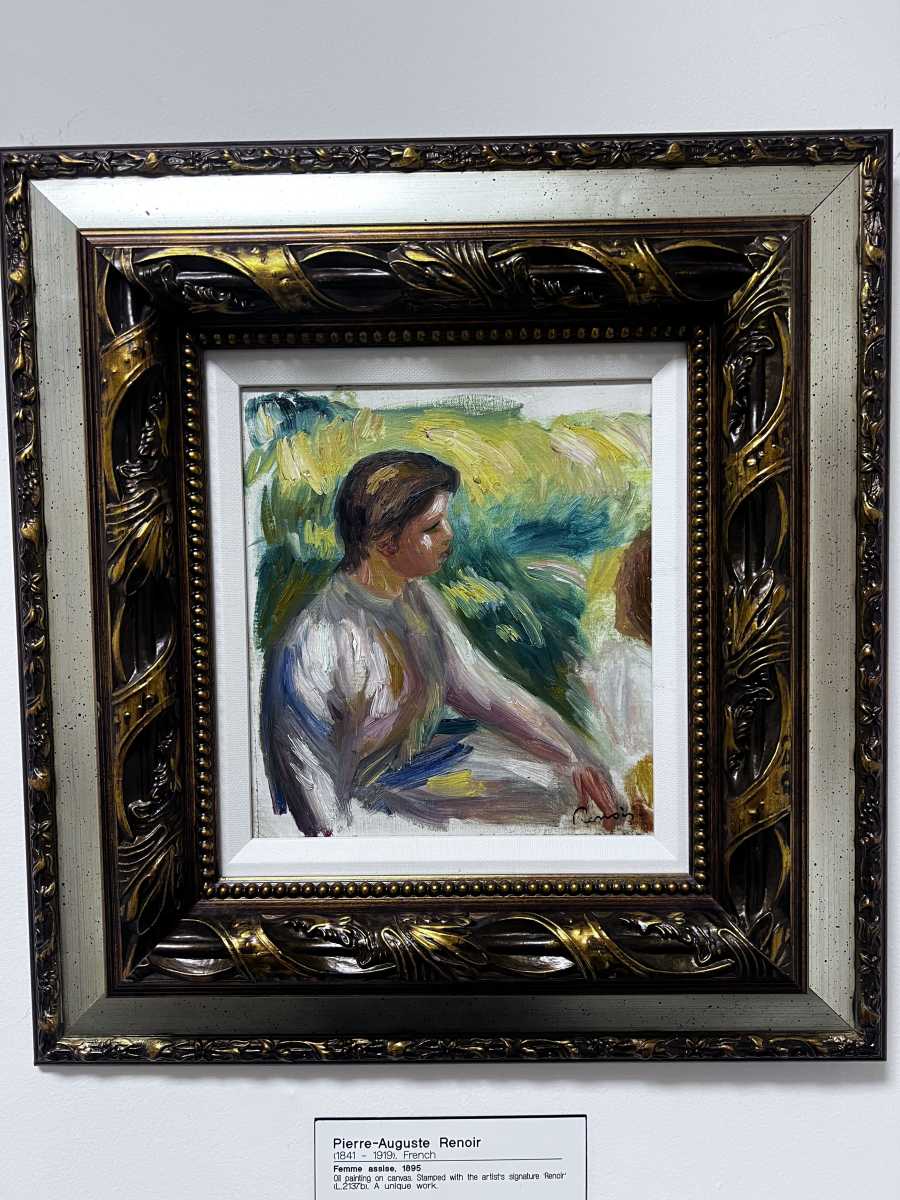

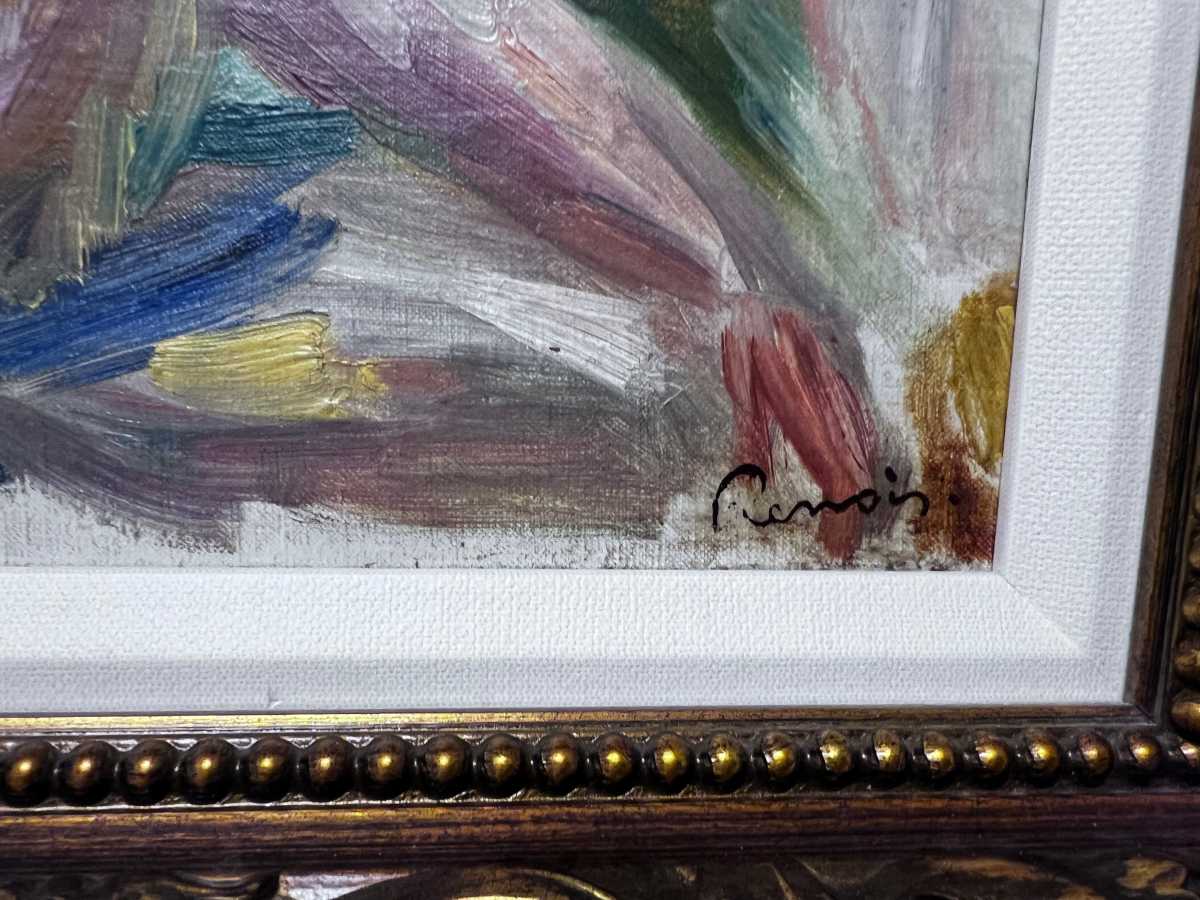

Select works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir are now on display at Park West Gallery in Soho. This is an invitation not only to view history, but to assume the honorable role of carrying it forward.

His decision to center joy was not frivolous. It was a declaration that the interior life—our capacity to feel, to enjoy, to savor—cannot be surrendered simply because the world commands efficiency. Renoir’s canvases are sanctuaries of lived time. They do not merely depict leisure; they preserve how it feels to be profoundly, vividly alive.

Renoir emerged in 1841 into a France in flux. Paris was in the midst of aggressive transformation, its medieval neighborhoods demolished and refashioned under Haussmann’s sweeping plans. Industry surged forward, altering the rhythms of work and rest, while photography challenged tradition by capturing reality with unprecedented accuracy. The art establishment, governed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, demanded historical grandeur and technical polish, leaving little room for what was immediate, sensory, or unguarded.

Within this environment, Renoir joined a constellation of young painters—Monet, Morisot, Degas, Pissarro—who rejected the academy’s rigidity and pursued the world as it unfolds in front of the eye. This movement, later known as Impressionism, changed the trajectory of visual culture. Its purpose was not exact representation, but the interpretation of sensation: the shimmer of sunlight, the murmur of crowds, the fleeting gestures of shared life.

Renoir occupied a singular position within the movement. While some of his peers chased the atmosphere of landscape or the dynamism of urban spectacle, he repeatedly returned to the human form. He believed that connection—whether between lovers, friends, or strangers gathered in light—carried cultural weight. In his work, the body becomes a site of memory, communication, and meaning. He defended pleasure as something intellectually serious, worthy of documentation and reverence.

During a time when labor was being standardized and time itself commodified, Renoir insisted that the capacity to feel joy was not indulgent but essential to the dignity of being human.

The importance of this philosophy resonates powerfully today. Arts funding is diminishing across cities and institutions. Museums are pressured to justify their relevance to rapidly shifting public attention. Cultural programming is increasingly influenced by political tides, corporate interests, or controversy-driven discourse.

Censorship has again entered the conversation with alarming ease. The question facing us is not whether art is admired, but whether society believes art has the right to exist freely, thoughtfully, and without apology.

Collecting art has therefore become an act of stewardship—and, in many ways, quiet revolution. To acquire a work by Renoir is to assert that tenderness holds value even when the world turns sharp. It is to affirm that beauty deserves protection, that history must remain accessible, and that culture is not something we observe passively, but something we uphold.

The recent auction of the Estée Lauder Companies’ collection at Sotheby’s underscored this truth. Impressionist and modern works were recognized not merely as objects of aesthetic pleasure, but as vessels of heritage, continuity, and identity.

Renoir’s paintings reside today in the Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, and many of the world’s most discerning private collections. They endure because they speak to something fundamental: the insistence that human closeness has meaning.

Renoir reminds us that art is not supplemental to culture—it is culture. It is the record of our tenderness, our gatherings, our laughter, our afternoons spent claiming time back from urgency. To appreciate Renoir is to declare that the internal life matters, that softness is not weakness, and that civilization is measured not only by its structures, but by its ability to feel.