Since opening on Broadway, “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child”—the stage sequel that extends J.K. Rowling’s wizarding saga decades beyond the original books and films, with Harry, Ron, Hermione and Draco now middle-aged parents—has been a moving target: artistically ambitious, commercially resilient, and constantly evolving in response to a changing theater economy.

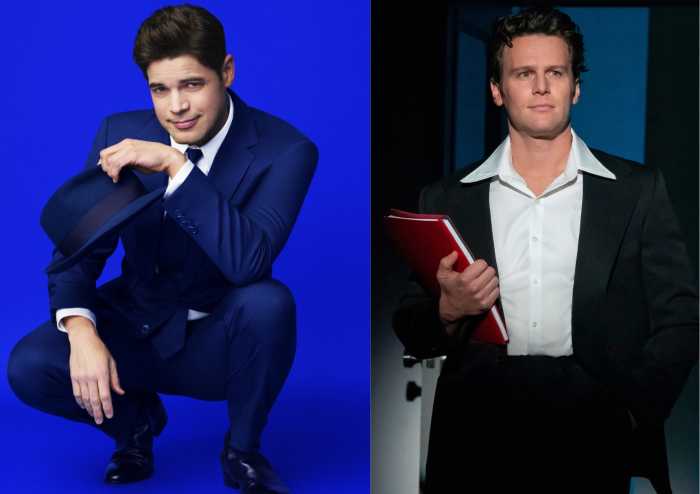

But nothing in the show’s long trajectory compares to what happened when Tom Felton joined the cast this season to reprise Draco Malfoy, the role he played across eight blockbuster Harry Potter films. Almost overnight, “Cursed Child” surged to the top tier of Broadway box office grosses—not because of a marketing tweak or a seasonal rebound, but because of a single casting decision.

When the production opened in 2018, it did so as a maximalist statement: a two-part epic requiring audiences to commit an entire day—or two successive nights—to experience the full story. It was a bold artistic gamble and, initially, a commercial one that paid off. But even before COVID, that momentum had begun to taper. The commitment required by the two-part structure increasingly narrowed the audience, and weekly grosses were winding down.

After the COVID shutdown, “Cursed Child” returned in a drastically reconfigured form. The two-part structure was collapsed into a single performance. The running time was trimmed. The storytelling was streamlined. And even after reopening, the show continued to be cut and refined, with further reductions to its length. While purists debated what was lost in the process, the box office delivered a clearer verdict: audiences were far more willing to say yes to one performance than to an endurance test.

Then came Felton. His casting didn’t just increase demand; it fundamentally reframed the show. Suddenly, “Cursed Child” became the place where audiences could watch one of the defining faces of the film series step into the stage version of the “Harry Potter” universe.

The timing magnified the effect. Winter is traditionally a difficult period for Broadway, with fewer tourists and more cautious local audiences. Yet “Cursed Child” has been selling like a peak-season hit, outperforming newer titles and emerging as one of the most commercially dominant shows in a sluggish stretch of the season.

Broadway has plenty of experience with celebrity appearances designed to juice short-term sales. “Chicago” has turned that strategy into a durable business model, cycling famous names through familiar roles in short stints that reliably move tickets without altering the show itself. In contrast, Felton’s casting doesn’t feel like stunt casting. He is returning to a character he inhabited for more than a decade on screen, in a story that is explicitly written to take place years after the films end. The appeal isn’t novelty; it’s continuity.

“Cursed Child” is not a retelling of a familiar story but a sequel that depends on the audience’s long-term relationship with these characters. Draco Malfoy isn’t a cameo or a wink—he’s integral to the play’s exploration of parenthood, regret, and inherited identity. Felton’s presence deepens that arc rather than distracting from it, allowing audiences to collapse the distance between the films they grew up with and the stage story unfolding in front of them.

Expectations around future “Harry Potter” casting should remain modest. Daniel Radcliffe and Emma Watson, both of whom have carefully shaped post-franchise careers far removed from “Harry Potter” nostalgia, are unlikely to follow Felton’s lead. While it isn’t impossible that Rupert Grint could one day join the show, Ron Weasley is a comparatively minor supporting character in “Cursed Child.”

Felton’s success may point toward a future in which new stage works based on famous films and other intellectual property are conceived from the outset as sequels—stories designed to invite original performers back into roles that audiences have aged alongside. That may be a more compelling proposition than watching an actor recreate a performance they already gave onscreen in a stage version of the same story.