With Cabaret bidding au revoir, is it a sign that Broadway’s economic structure is finally reaching its breaking point?

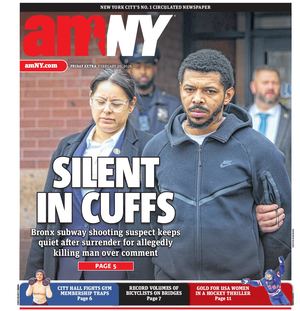

Last week, it was announced that the $24 million Broadway revival of “Cabaret,” which transformed the August Wilson Theatre into an immersive nightclub at enormous cost, will close earlier than expected after months of disappointing grosses and apparently at a total loss. Although the official end date had previously been set for Oct. 19, to coincide with the end of Billy Porter’s run as the Emcee, his recent illness forced producers to move the closing up to Sept. 21.

The closing, paired with a lawsuit from an investor demanding repayment of his $50,000 contribution, has become a flashpoint in the debate over whether Broadway’s current economic model is sustainable, especially for large-scale musical revivals.

The production, which originated in London (where it continues to run), faced far steeper challenges in New York. Producing in London is considerably less expensive, and its audiences were more receptive to the divisive staging. On Broadway, the same concept required premium ticketing and constant star power just to cover weekly costs.

Directed by Rebecca Frecknall, the revival gutted and rebuilt the August Wilson into an in-the-round Berlin nightclub with a new mezzanine level and cocktail tables. The refit alone cost millions and saddled the show with staggering overhead. Audiences were greeted by a 75-minute preshow of cabaret acts and drinks—dazzling, but expensive, and often overshadowing the musical itself.

Combined with the show proper, attending became a four-hour experience.

The production also leaned heavily on upsells: stage-side dining at $105, Pineapple Room packages at $95, and other premium add-ons, plus specialty cocktails aggressively marketed during the preshow. For many theatergoers, the overall cost was unusually high, and they were only willing to pay for it when Eddie Redmayne was in the cast.

Redmayne’s grotesquely twisted Emcee drew both fascination and ridicule (his Tony Awards performance went viral), but kept the house sold out. Even then, given his likely salary and the refit costs, the show was probably only breaking even.

After his departure, Adam Lambert and Orville Peck both earned praise as the Emcees, but box office returns remained modest. By the time Porter took over, sales were slipping badly. The decision to close following his engagement and then move the end date up due to his illness suggests that Cabaret was never financially viable. Even if the investor lawsuit lacks merit and is quickly dismissed, it highlights that perception.

Musical revivals on Broadway rarely run long. Because audiences already know the shows, they tend to open strong, as longtime fans rush to see a new staging, but sustaining momentum after that initial wave, especially once a star leaves, is far harder. The lone exception is “Chicago,” which thrives thanks to its stripped-down design, low costs, and steady stream of replacement stars.

“Cabaret,” another Kander and Ebb classic, seemed to want to emulate the “Chicago” model but at a far higher cost. Producers reportedly hoped to lure pop stars for limited runs. Rumors swirled about Miley Cyrus and Sabrina Carpenter, and Jessie J confirmed she had been offered Sally Bowles but declined. Without such marquee names, the show had little chance of survival.

The closure of “Cabaret” coincides with revelations that the acclaimed, frequently sold-out revival of “Sunset Boulevard” also failed to recoup its investment. If even a smash hit cannot pay back its backers, the economics of Broadway revivals look increasingly shaky.

This “Cabaret” will be remembered as both audacious and unsustainable, collapsing under the weight of its own ambitions. With producers’ rumored hopes of pop superstars fading into fantasy, the Kit Kat Klub will soon close its doors – at least until the show’s next revival in another decade or so. The real question is whether “Cabaret” is merely one troubled production or a flashing warning sign that Broadway’s reliance on costly reinventions and star-driven revivals has become untenable.