BY ANDY HUMM

Our greatest living playwright has died, felled by the coronavirus pandemic in Sarasota, Florida, on March 24. Terrence McNally, who was an out gay artist in the 1960s when few risked openness, was 81. His work boldly broke ground on gay themes and often wrestled with the AIDS crisis and racial questions as well.

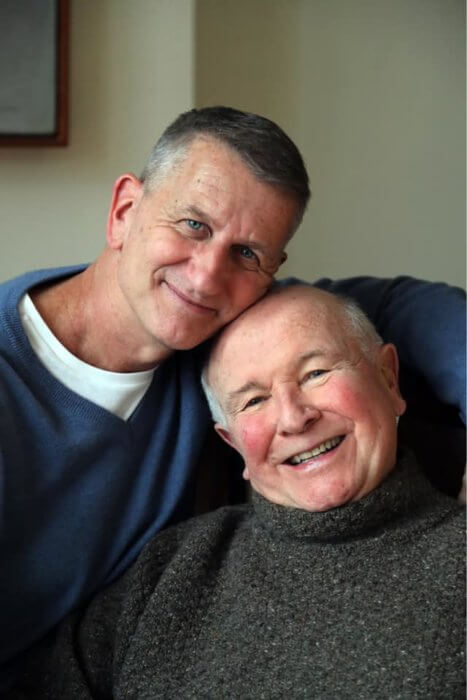

He is survived by his longtime partner and husband, Tom Kirdahy, who is one of Broadway’s leading producers (“Hadestown,” “The Inheritance”).

McNally won four Tony Awards — Best Plays “Love! Valour! Compassion!” (1995) about a group of gay male friends written and set in the darkest days of the AIDS pandemic and “Master Class” (1996) about opera diva Maria Callas, and Best Book of a Musical for his adaptations of Héctor Babenco’s film of “Kiss of the Spider Woman” (1993) and E.L. Doctorow’s novel “Ragtime” (1998). He was also nominated for Best Book of a Musical for “The Full Monty” (which he adapted from Sheffield, England, to upstate Buffalo) and the last Kander & Ebb collaboration, “The Visit,” Best Play for “Mothers and Sons” about an unaccepting mother of a gay son meeting with his lover 20 years after her son’s death from AIDS — a sequel to his Emmy Award-winning teleplay “Andre’s Mother” set at her son’s funeral. He was presented a special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Theater just last year.

McNally was a lung cancer survivor and had been suffering from pulmonary disease, often seen carting portable oxygen in recent years — conditions that contributed to his succumbing to the coronavirus. But despite Terrence’s age and frailty, many were gutted by the news of his passing in this already dark time compounded by the willful and daily negligence of President Donald Trump.

Kirdahy himself posted on Facebook, “Love Won. RIP Terrence,” with a gorgeous loving picture of them together.

“I am bereft,” writer Kevin Sessums posted on Facebook. “My heart is broken for our theatre community and his husband Tom Kirdahy.” Sessums spoke of “how lucky they were to find each other.”

Tom Viola, longtime director of Broadway Cares/ Equity Fights AIDS, posted that McNally was one of the group’s “founding fathers” because he “believed that the most important function of theatre is to create community.” He wrote that McNally “gave voice to both the voiceless and those who can stand tall, not only through his art but also his actions. He was a steadfast champion for civil and LGBTQ rights onstage and off. He gave us unforgettable characters who told delicate, brilliant, courageous, and unforgettable stories that reflected the lives and dreams, joys and heartbreak of us all.”

Harvey Fierstein wrote that he was “broken hearted. But let’s always remember that Terrence was anything but a victim. He was a lover and fighter and an artist and a voice for our people. He was a victor. The man didn’t write his heart out. He wrote OUR hearts out!”

Nathan Lane put McNally’s impact on his life in succinct terms, writing, “I’d have no career without Terrence McNally.”

While McNally broke barriers all his life by being out and through bringing gay content to the stage, “Corpus Christi” in 1997 was his most controversial work as it retold the story of Jesus and his apostles through modern-day gay men in Texas. Besieged with bomb threats from right-wing religious zealots, Manhattan Theatre Club canceled the play. When theater artists stepped forward to protest the censorship — playwright, novelist, actor, and director Athol Fugard threatened to sever his relationship with MTC — the theater relented and opening night saw metal detectors for the audience and large dueling demonstrations from the anti-gay Catholic League and LGBTQ groups.

McNally, born November 3, 1938, in St. Petersburg, Florida, grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas, where he nevertheless was exposed to Broadway theater, including through trips to New York. He moved to the city in 1956 to attend Columbia, majoring in journalism but studying Shakespeare and writing musicales. Right out of college, John Steinbeck hired him as an assistant as he and his family took a trip around the world. McNally later wrote the libretto for an adaptation of his “East of Eden.”

McNally worked as the stage manager for the Actor’s Studio in New York. He once said that he decided to become a playwright “because it was a good way to meet guys.” He did meet budding playwright Edward Albee in 1959 soon after Albee’s debut with “The Zoo Story” and they were an item for four years during which Albee turned out “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” and McNally wrote “This Side of the Door” that starred Estelle Parsons. Part of the reason they parted was Albee’s then-reticence about being publicly gay.

McNally made his Broadway debut in 1965 with “And Things That Go Bump in the Night” at age 25. While panned, it included a gay character played by Robert Drivas who would become his partner. Drivas died of AIDS in 1986 at 50.

McNally’s Broadway farce “The Ritz” (1975), set in a gay bathhouse, was a big hit for Rita Moreno and was made into a film. He wrote the book for Kander & Ebb’s “The Rink” with Liza Minnelli and Chita Rivera, and the book for the Disney musical “Anastasia” in 2017. His 1982 “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune” was revived for the second time on Broadway in 2019 with Michael Shannon and Audra McDonald.

Among his 36 works, McNally also wrote off-Broadway gems from “Lisbon Traviata” (1989) and “Lips Together, Teeth Apart” (in 1991 with Nathan Lane) to “A Perfect Ganesh” (1993) and “Some Men” (2006) set in Greenwich Village, where he first lived in New York, during the Stonewall Rebellion. He wrote numerous opera librettos and plays about opera.

McNally’s longest term relationship was with Kirdahy whom he met in 2001 at Guild Hall in East Hampton where Kirdahy was hosting a theater panel that also included Albee and Lanford Wilson for the East End Gay Organization.

“When I saw him,” Kirdahy told The New York Times, “I thought he was completely adorable.”

McNally had lost another partner to AIDS in 2000 and was not expecting to be with anyone else at 63, but they entered into a civil union in Vermont in 2003 and were married by Mayor Bill de Blasio on June 26, 2015, just hours after the US Supreme Court legalized marriage equality nationwide.

Viola related how in Broadway Cares’ 1992 book “Broadway Day & Night: Backstage and Behind the Scenes,” in the midst of the AIDS crisis, McNally wrote, “I am in mourning not the Broadway that was but the Broadway that AIDS has seen to it will never be.” In the face of that stark reality that took so many Broadway greats, McNally urged his community to “do the best work we can. It’s the only fitting memorial to those we have loved and lost.”

McNally’s loss in the current pandemic on top of the complete absence of live theater and the mortality that we are all facing hits hard. The traditional honor of dimming the lights of Broadway in honor of the greats will have to wait for him as will filling a Broadway theater for a memorial. We will, however, always have his incredible work and his admonitions on what’s worth doing.

When you write about what we are living through now, keep Terrence McNally in your head: “Write plays that matter,” McNally said. “Raise the stakes. Shout, yell, holler, but make yourself heard. It’s time for playwrights to reclaim the theater. We do that by speaking from the heart about the things that matter most to us. If a play isn’t worth dying for, maybe it isn’t worth writing.”

This story first appeared on gaycitynews.com.