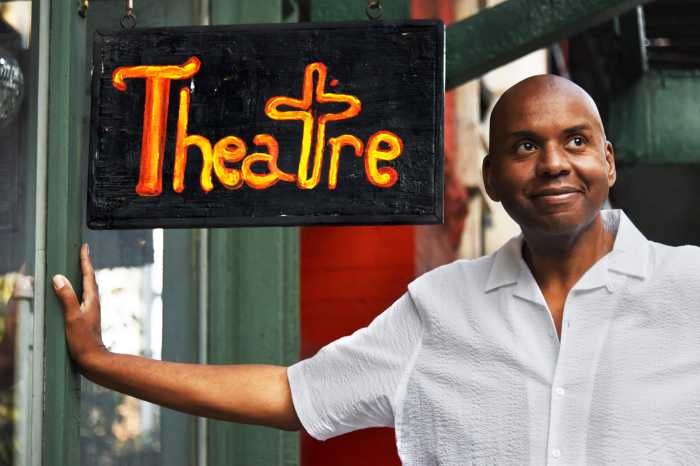

“Chicken & Biscuits,” a new family comedy by actor Douglas Lyons (who has appeared on Broadway in the ensembles of “The Book of Mormon” and “Beautiful”), makes for a great success story – if not necessarily a great play.

The play managed to make its world premiere at the Queens Theatre in Flushing Meadows Corona Park mere days before the pandemic shut down virtually all live theater in New York City.

Over a year later, it was announced that “Chicken & Biscuits” would transfer to Broadway, making it part of a historic surge of plays by Black writers on Broadway following the pandemic including “Pass Over,” “Lackawanna Blues,” “Slave Play,” “Thoughts of A Colored Man,” “Clyde’s,” “Skeleton Crew,” and “Trouble in Mind.”

But unlike all those other plays, “Chicken & Biscuits” is a conventional, sitcom-style, feel-good comedy. There is absolutely nothing wrong with having a play like that on Broadway. In fact, it’s refreshing to have a lighter option available for those who are not interested in an experimental and challenging piece such as “Pass Over” or “Slave Play.”

The cast includes veterans from the Queens production and familiar Broadway actors including Norm Lewis (“Porgy and Bess,” “Once On This Island”), Michael Urie (“Torch Song,” “Buyer & Cellar”), and NaTasha Yvette Williams (“Waitress,” “Porgy and Bess”).

Set in and around a church before, during, and after a funeral, a Black family is mourning the death of its patriarch, leaving his son-in-law (Lewis, who gets the chance to sing a little) to take over as the church’s pastor and deliver his eulogy. That being said, “Chicken & Biscuits” is primarily concerned with tensions and dysfunctions within the extended family, culminating in a mystery guest appearance and surprise revelation at its climax.

I really wish I had liked the play, which is billed as running 100 minutes without intermission but really runs just over two hours in length.

It is affectionate and well-meaning, preaching love, reconciliation, and acceptance. But unfortunately, it is cliched and tedious, with numerous scenes that drag on endlessly. One gets the feeling that Lyons one day decided that he wanted to write a play up with this. (According to an interview with The Undefeated, Lyons wrote the play while working as an actor because he needed something to do backstage.)

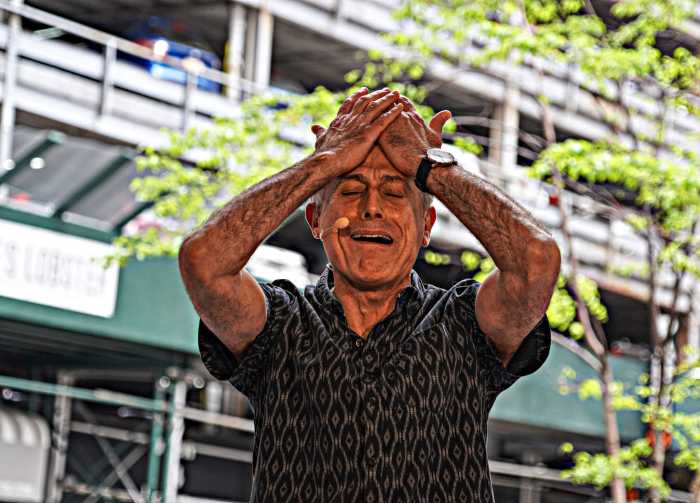

The production (staged by Zhailon Levingston, who is now the youngest Black director in Broadway history) relies heavily on mugging from the actors, especially Urie, who does his standard shtick of exaggerated facial expressions and manic reactions. It works best during the funeral sequence, at which point theatergoers are made to feel as if they are part of the church service. At my performance, quite a few people responded to the funeral speeches in a call and response style.

Just in case you are wondering about the title, the play concludes with a meal of chicken and biscuits. Once theatergoers no longer need to wear face masks, they may get a kick out of eating chicken and biscuits during the play. “Chicken & Biscuits” may very well have a big future ahead in dinner theater.

Circle in the Square Theatre, 1633 Broadway, chickenandbiscuitsbway.com. Through Jan. 2.