Four years after New York City reached the highest number of shootings in several decades — a number that has since dropped sharply — New York City’s district attorneys continue to balance constituents’ calls for progressive reforms with mandates to fight violent crime.

While each borough faces its own unique challenges and voter preferences, in 2025 every borough’s DA was united behind a common legislative goal: rolling back recently approved reforms that instituted stricter rules of evidence for prosecutors — particularly changes to the state’s speedy trial laws that DAs say have led to an increase in dismissals for criminal cases.

In this respect, the DAs largely got what they wanted. Gov. Kathy Hochul announced that the state budget would contain a bill that would walk back parts of the state’s 2019 discovery laws to prevent case dismissals on what the DAs characterized as technicalities.

“We’re hoping to have proportionality in the range of sanctions that the judge can impose when there’s a good faith missing of a deadline,” Alvin Bragg told amNewYork Law prior to the bill’s passage.

The 2019 discovery law requires prosecutors to share evidence with defense lawyers on an accelerated timeline or face sanctions including the possible dismissal of the case. Hochul had originally proposed changes that would stop the requirement of sharing “related” evidence, which prosecutors claimed was overburdensome. What they got was a compromise. As City & State reported, the language in the final budget deal still gave judges the ability to decide on how best to address missing evidence, including but not limited to dismissal.

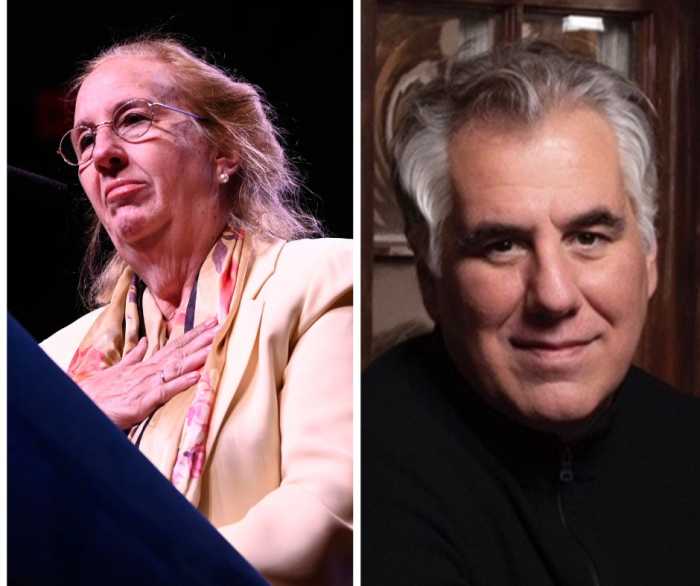

In the Bronx, District Attorney Darcel Clark said that she believed the changes would help set her office right. Clark reports a staggering increase in dismissal rates—rising by around 20% in felonies for misdemeanors from 2019 to 2024. She blamed the rise for plummeting staff morale and for giving rise to a “paper pusher” culture in her office.

“I’ll be able to retain my staff now, because so many of them were quitting,” she told amNew York Law shortly after Hochul passed the rollback in the budget. “It was insurmountable for them. They worked so hard on these cases, and then it gets dismissed on the technicality.”

Clark, who has been in office since 2016, said her tenure has been defined by a struggle for resources, arguing the Bronx is chronically underfunded compared to Manhattan and Brooklyn. To combat the highest crime rates in the city, she had sought $25 million for new staff. What she got was an additional $6 million for the fiscal year 2026.

In addition to uniting differently resourced district attorneys, the discovery rollback united prosecutors across wide political chasms. Bragg, a prosecutor who first ran as a reformer intent on reducing incarceration, found himself in the position of joining forces with Staten Island District Attorney Michael McMahon, who has called Bragg’s policies around not prosecuting fare evasion and prostitution something that has “no place” in the district attorney’s office.

But in Staten Island, McMahon has also toed the line between reforms to the district attorney’s office that could be characterized as progressive and his conservative constituency in the borough.

McMahon defined his approach as district attorney early on by creating a successful diversion program to connect opioid addicted individuals in the borough with supportive services rather than prosecute them. His Heroin Overdose Prevention and Education (HOPE) program successfully diverted 2,000 people into treatment.

While it cut against a strict law-and-order approach to prosecution, McMahon told amNewYork Law he sees drug addiction differently than other categories of crime.

“Listen, I’ve got to sell these things to the larger community in Staten Island,” McMahon said. “So if I am dismissing cases, if you will, I’ve got to keep the support of the people of Staten Island for what I’m doing.”

McMahon’s efforts collided with sweeping changes to criminal justice under the Legislature’s bail reform program, which he believed to disrupt his signature HOPE program, arguing that getting rid of prolonged detention sidesteps the “initial engagement” necessary to convince an addict to seek help at their lowest point.

In Brooklyn, District Attorney Eric Gonzalez maintains the balance of being a progressive prosecutor with a sense of pragmatism by avoiding blanket policies around non-prosecution. On fare evasion, for example, Gonzalez told amNewYork Law that he prosecutes “transit recidivists” while dismissing cases that stem from poverty.

That approach has yielded clear political benefits for Gonzalez, who won reelection unopposed for his third term in November. He was recently named on a shortlist of potential candidates that Hochul is potentially eyeing as her running mate for lieutenant governor in her campaign for reelection 2026.