New York’s Grieving Families Act, which would have overhauled a wrongful-death statute that dates back to 1847, has just been vetoed by Gov. Kathy Hochul for the fourth time. She criticized lawmakers for not changing the bill to her liking. Lawmakers, lawyer groups, and victims of wrongful deaths criticized her for supporting special interests, including insurance companies, hospital associations, and defense lawyers who typically represent municipalities and individuals sued in tort lawsuits denies.

This law enlarges monetary damages for the wrongful death of a loved one. It authorizes juries in wrongful death cases to award monetary damages not only for financial losses like medical costs, funeral expenses, diminished inheritance, and loss of love and companionship, but also for the grief and anguish caused by the victim’s death.

New York State is an extreme outlier. Similar provisions that authorize tort damages for “grief and anguish” can be found in 48 other states. Only Alabama has a law as antiquated as New York’s. The proposed law gives a jury in a wrongful death trial not only the need to assess the financial value of the victim’s death to the surviving family, but also to make a determination of the emotional value to the family from the wrongful death of a loved one.

A grieving father recently wrote this in an amNewYork op-ed: “My son, Ethan, was just 14 years old when a drunk driver took his life. Ethan was full of kindness, joy, ambition, love, and happiness. His future was stolen in an instant. And yet, under New York’s outdated law, Ethan’s life is considered to have absolutely no value for my family’s grief, and the deep pain my family feels is completely ignored.”

Ethan’s father is absolutely correct. To the extent the present law gives no value to a parent’s anguish from the loss of a child, the law is unfair and unjust. Consider the perverse consequences from New York’s outdated wrongful death law, particularly with respect to wrongful deaths of children, or persons who do not have earning power and thus lack monetary value. Under New York’s current law, if an adult with earning power is killed due to another person’s wrongdoing, maybe a very wealthy person, his family can seek compensation based on the victim’s wealth or the monetary value stemming from the lost relationship. But if a child, a stay-at-home parent, or a retired grandparent is killed, their life may have no appreciable monetary value; they may not have wealth and do not earn a living. They therefore would not receive financial compensation.

Hochul’s first veto, two years ago, was attributed by the media to the governor’s pique at Democrats in the State Senate for rejecting her nominee for chief judge of New York’s Court of Appeals. But her subsequent vetoes have been substantive. She claims that enlarging tort damages to include not just financial losses but also “emotional losses” will greatly increase insurance premiums, health care costs, and be very bad for New York’s economy.

Indeed, the bill is opposed by a raft of special interests, including insurance companies, hospital associations, and defense lawyers who typically represent municipalities and individuals sued in tort lawsuits. Lawyers who oppose the bill claim that the bill was “bulldozed through the legislature” without considering the due process rights of people that are sued.

Hochul’s vetoes seem to echo that sentiment. She said in a 2023 op-ed in the Daily News that the bill was missing a “serious evaluation of the impact of these massive changes on the economy, small businesses, individuals, and the state’s complex health care system.”

Hochul has indicated that an eventual compromise is possible but said that she would need to see a substantial paring down of the bill to get on board.

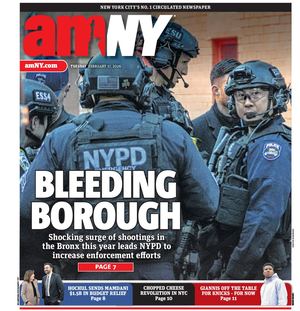

The governor is facing re-election next year. She is a moderate Democrat who wants to position herself as a pragmatic, law-and-order liberal who wants to push criminal justice reform. She recognizes that if people suffer a loss due to someone’s wrongful conduct, the person at fault should pay.

The several versions of the bill are really not that different. Aside from the monetary damages noted above, the bill includes damages for “grief or anguish caused by the decedent’s death.” The bill extends the statute of limitations from two years to three years and increases the pool of persons who can recover beyond those named in the decedent’s estate. It applies to all causes of action that have accrued on or after Jan. 1, 2022.

The newest version has not altered the governor’s misgivings. Whether the legislature can override her veto remains to be seen.

According to State Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal, who has sponsored the bill, Hochul’s veto “denies families justice. Our law creates a two-tiered system where the lives of the wealthy are acknowledged while everyone else is treated as invisible, and families are told their grief has no legal meaning.”

As history shows, the battle between insurance companies and people of modest means is a recurring phenomenon in America. And insurance companies usually win.

New York’s antiquated wrongful death is seriously deficient and needs to be updated with a modern and humane law that seeks to level the litigation field so that the value of every life — and death — should be compensated fairly and equally.

Bennett L. Gershman is a distinguished professor at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University