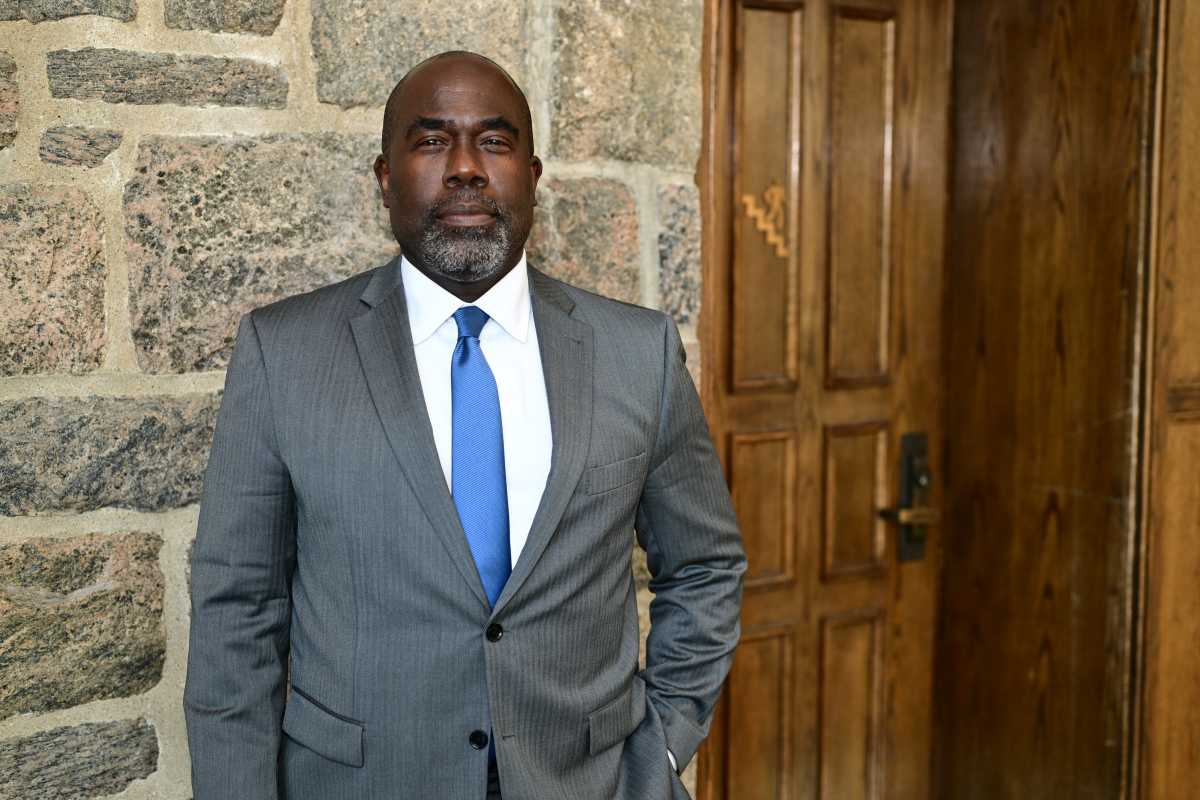

When Pace University law school dean Horace Anderson talks about campus identity, he leans heavily on the concept of social responsibility.

Anderson compared his attitude to the “with great power comes great responsibility” ethos from the Marvel Universe.

“[Our] goal is to give [students] a sense of how important it is to use the power that they will wield as a lawyer to bring about good in the communities that they live in and work in,” he said. “And so we want to empower them and we want to make communities strong and do service.”

To this end, he’s pursued mission-driven goals. As dean, he’s built on the school’s reputation as having one of the first and most recognized environmental law programs in the country to create a sustainable business law program that marries the school’s environmental law curriculum with the business community.

In the realm of public interest law he also spearheaded the Access to Justice Project, which focuses on providing direction and referrals to local community members who are looking for help with a legal problem.

But that sense of duty doesn’t have to fit one form. It could mean pro bono work, serving on non-profit boards, or working in public interest or government roles.

“What it means to me is that no matter where you find yourself after graduation, you are looking for opportunities to serve,” he said.

And it doesn’t mean that the call to serve should feel like an obligation. Anderson’s own career was shaped by a sense of intellectual curiosity. He moved from startups to law, and then from law practice to legal education out of a desire to explore legal theory behind intellectual property and technology.

Anderson has served as dean of the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace since the end of 2019 after working in administrative posts and teaching at the school.

“You’re going to be adapting and looking for things that continue to interest and challenge you for decades to come. And so think about your career that way. Think about it as a series of steps that will overall bring you a whole bunch of different types of fulfillment,” Anderson said.

As the son of Jamaican immigrants who moved to Brownsville, Brooklyn to help their children pursue higher education, he said he prioritizes empowering students, many of whom are first-generation or from immigrant backgrounds, to use their legal education “to impact their own lives and change their families’ circumstances.”

For him, the opportunity to serve the school as dean sprung from a series of choices he made pursuing abstract questions about ownership and control and dissemination of technology. When the opportunity to teach presented itself, he saw a way to have an impact on the next generation of lawyers.

“This wasn’t something I wanted to do my whole life, but in preparing myself along my entire arc, I was always ready for opportunities and ready [to use] what I already knew to help me at the next step,” Anderson said. “And I try to instill that in our students as well.”

Path to deanship:

Prior to joining the law school, Anderson practiced at White & Case LLP, a global, white-shoe law firm, where he focused on intellectual property, privacy and data protection.

“I really enjoyed the subject matter,” he said. “It was all cool subject matter, cool client stuff, fairly cutting edge stuff, but I always wanted to take it in directions that I found interesting, which, when you’re a lawyer, you take things in directions that help your clients’ cause, not necessarily something that you find the most interesting.”

He got connected to Pace through a colleague and saw a way to pursue the theoretical side of law. But when he got to the green lawns and gothic buildings of the Westchester County law school, he found an intimate environment where faculty had a lot of interaction with students.

“It’s a low-rise campus. So we don’t spend a ton of time in elevators,” he said. “We spend a ton of time moving around horizontally, and so we see each other and we get to know each other.”

The school places a strong emphasis on “learning by doing” through a wide array of clinics and “externships,” where students shadow professionals, gaining insights into a field.

Several of the programs Anderson listed as achievements as dean entailed looking for new applications of public interest law, sometimes with a blend of business or technology.

In the Access to Justice program, a lab course partners law students with computer science students to find technological solutions to problems people have accessing the legal system. For example, a student group created a mobile app designed for tenants to document and timestamp communications with their landlords, helping to level the playing field in court proceedings.

The sustainable business program is designed to train students to work within corporate legal departments and law firms to promote sustainability. At its annual conference earlier this month, Justin Driscoll, president and CEO of the New York Power Authority, gave a speech drilling home the importance of private-public partnership in meeting climate goals.

“Our program is about building a community of corporations, small businesses, nonprofits who have access to information and access to a group of others who are all trying to solve some of the same problems,”Anderson said.

Anderson’s path to becoming dean was a two-step process: first, transitioning from intellectual property law practice to law teaching, and then moving into administration.

“I came here as a teacher, and so everything I’ve done as an administrator is based on what I think I understood as a teacher about what we need here,” he said.

His path into law was not a “given,” but what was in his household, he said, was the notion of higher education as a means of advancement. Out of his siblings, “two of the four have PhDs, “ he said.“[Those were] the seeds that were sown.”

But while his parents instilled a strong career drive, he did not have lawyers in his family or wider community growing up, which gives him a strong inclination to mentor first-generation law students.

“I tend to let students know, and I’m usually pretty explicit about it, ‘if you don’t know… what this is, I’m here to help you figure [it] out,’ ” he said, gesturing at the law school campus.

What concerns him in the realm of legal education is its affordability and a broader perception of higher education that devalues it. Undergraduate enrollment in the U.S. has been on an overall decline since 2011 when it reached its peak, and researchers expect it to keep falling. Anderson fears that will eventually end up affecting law school enrollment — a pipeline that he sees as crucial for the future of leaders of society.

While Anderson did connect the 20 percent national increase in law school applicants this year with a wave of students who want to be “ part of the policy direction of the country,” he said that their interests are not confined to one sector.

“There are students who want to be the general counsel for their family’s business, right?” he said. “We’ve got students who want to do immigration practice. We want students who want to be prosecutors, we want students who want to be defense attorneys. We want students who want to practice corporate law.”

In many cases, the sense of responsibility that Anderson tries to inculcate in students does lead to a career in public interest. He said about a third of graduates end up in public interest law or the public sector. From a numbers perspective, the approach is leading to positive outcomes. In 2024, the school reported its highest overall employment rate on record, with 94% of that year’s outgoing class finding a job.

“What I want to continue to hear from our employers is when our graduates walk in the door, they’re ready to go, and they are able to assign them work and put them on matters and know that they’ll get high quality work because they’ve already started to learn what it is to actually be a lawyer and do lawyers’ work,” Anderson said.