A flight attendant, data analyst, hair salon owner and three other adults sniff fumes wafting from paper slivers soaked with an odorant that smells like lily of the valley, a perfume note also known as “muguet” and most famously associated with Christian Dior’s iconic “Diorissimo” perfume.

“Think of Flonase,” prompts fragrance designer and instructor Raymond Matts. “They actually scent Flonase with muguet,” the French word for the delicate bell-shaped flowers, he explained.

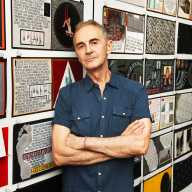

Matts, 53, a Manhattanite who has his own line of eponymous fragrances, teaches fragrance-fond New Yorkers how to become more olfactorily literate and scent-ually aware.

In his “Technique and Language of Perfumery” and “Advanced Perfumery” classes, taught in Pratt Institute’s Center for Continuing and Professional Studies in conjunction with Cinquieme Sens, fragrance fanatics learn how to analyze, appreciate and accurately describe what their nose knows.

People wishing to properly manufacture perfumes from scratch must go to France or apprentice to pros inside a fragrance house, Matts contends.

But in his certificate perfumery program (FIT also has one) fragrance aficionados learn how to identify top, middle and base notes, the ABCs of accords (blends of distinct notes that create new scent impressions) and what contributes to sillage (the degree to which a perfume lingers in the air).

In one recent class, Matts discussed fougeres, gourmands, aromatics, and aquatic compositions as students dutifully sniffed strips dipped into tiny jars of scent samples from the “olfactoriums,” identifying ingredients from ambrox to yuzu.

Matts stressed the revolutionary effect of “headspace technology” (the molecular analysis of odors using chromatography and mass spectrometry) that permits scientists to replicate scents in laboratories. “I hate that word ‘chemical.’ They’re man-made ingredients,” Matts said.

Dihydromyrcenol is a primary man-made ingredient in Davidoff’s “Cool Water,” which revolutionized “fresh” scents for men and led to a category of “sport” fragrances, Matts noted.

There were also consumer tips: Volatile top notes remain intact only about a year after bottling, so it’s not a great idea to buy perfumes of uncertain vintage on the second hand market.

If you find your affection for an old bottle undiluted, it’s probably because the ingredients you most appreciate have yet to degrade.

The difference in products such as “eau de parfum” (EDP) and “eau de toilette” (EDT) is one of concentrations, Matts continued: An EDP is supposed to have a concentration of 12% to 18% of active ingredients, with the balance a neutral base of alcohol and water.

EDT has an eight to 12% concentration and “eau de cologne” is even less than that.

And no, said Matts, in response to a question, there is no enforcement of these standards. Perfumes are supposed to be 20% to 40% “but nobody does 40% any more. Few even do 20% — it’s very expensive,” he said.

One unpopular strip contained “calone,” an odorant used to create a watery, marine-like impression in perfumes but instead gave off an acrid stench in pure form.

But that is where the magic lies, Matts explained: Calone brightens floral notes and strengthens citrus notes, citing L’Eau d’Issey and Calvin Klein’s “Escape,” as examples of calone-infused scents.

Matts also added another point: If a fragrance is made properly, “you don’t notice it as it is.”