BY TEQUILA MINSKY

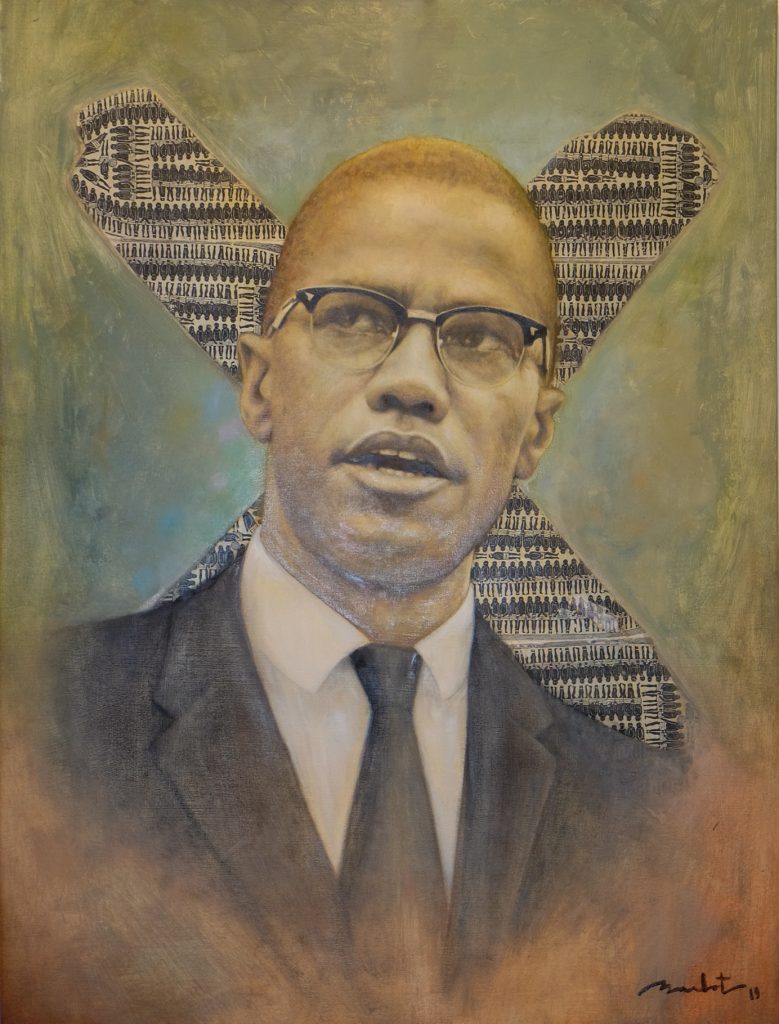

How does a Haiti-based painter end up having an exhibition of Black icons—including Harriet Tubman, Obama, Malcolm X, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, at 1199SEIU’s Bread and Roses Gallery on West 43rd St?

In 2018, Richard Barbot presented his portrait of Harry Belafonte to the legendary singer during a tribute for his 91st birthday, propelling this artist onto 1199’s radar. Not long after, Barbot was invited to exhibit at the Gallery for Black History Month.

With a handful of paintings already completed, it took Barbot about a year to paint the American iconic figures and the paintings from Haiti’s history included in this exhibit.

Barbot works big—his portraits are at least 4 feet by 3 feet, with his largest work 10 feet, the middle painting of a triptych entitled Window of Hope that stretches more than 22 feet and takes up the whole far wall of the gallery.

To ensure the arrival of his work, the artist hand carried his rolled-up paintings in a custom-made bag onto the airplane, and once in New York, stretched them on frames. He even completed a few paintings after taking temporary residence in Brooklyn.

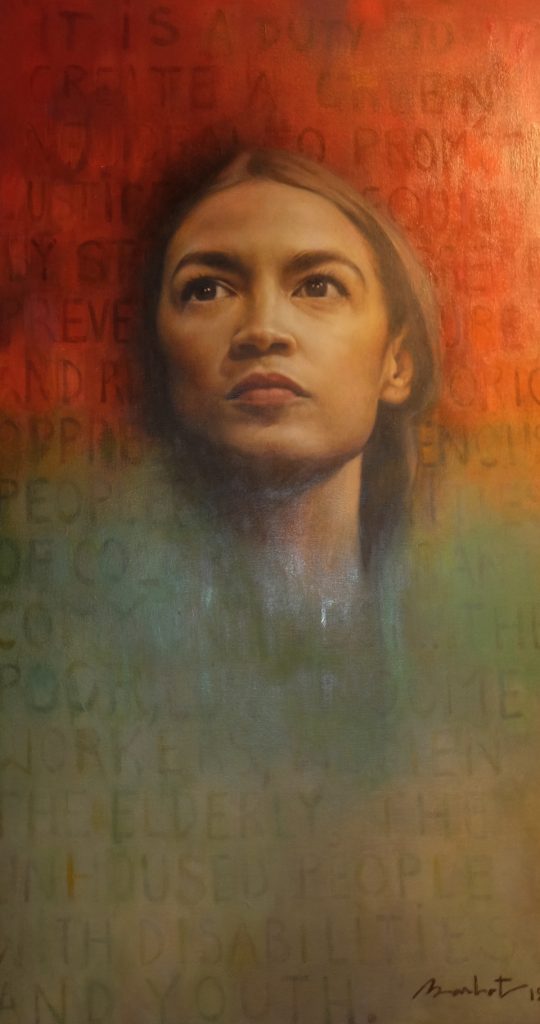

Curated by Leslie Williams, the exhibit includes portraits of AOC-Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, and Rita Valdivia, Bolivian poet and leader in Bolivia’s Army of National Liberation, who died in combat after her 23rd birthday.

His portrait emphasizing Obama is subtitled Path of Freedom and includes imagery of Toussaint Louverture, Lincoln, MLK and Nelson Mandela.

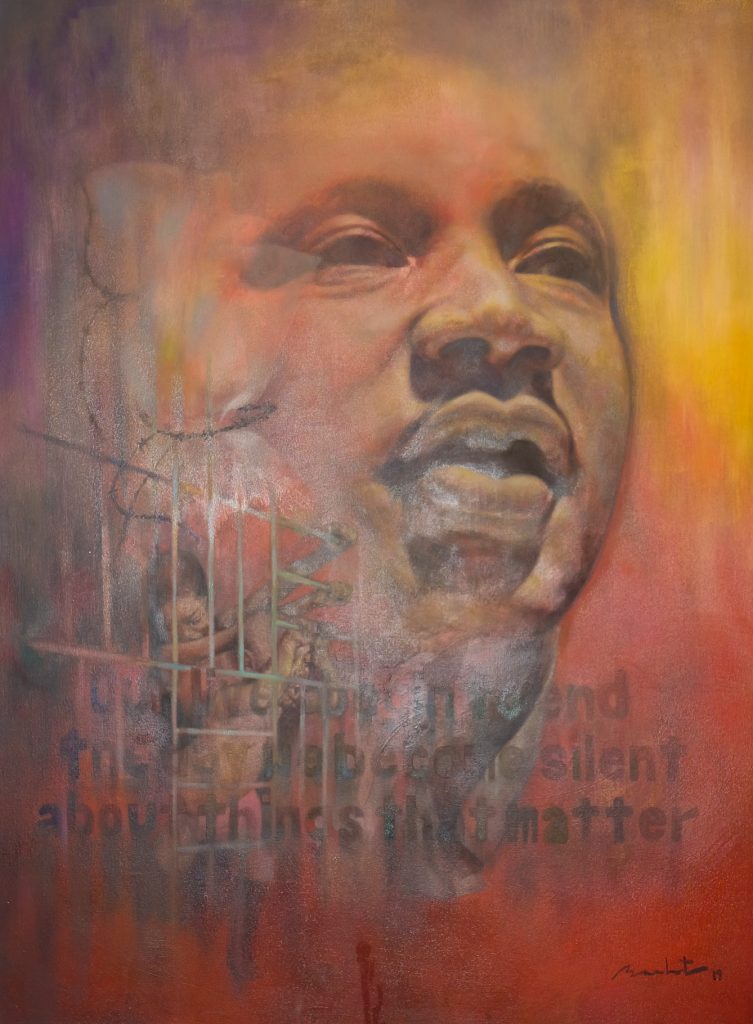

Martin Luther King earns his own portrait where in the notes alongside Barbot quotes the civil rights legend, “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

Barbot writes, “Despite the passing of time, his words still carry the same weight, intensity and resonate in our current society.” And, reacting to the current administration’s cruel policies toward the children at the border, Barbot says, “In the face of this violence, silence becomes deafening.” Barbot incorporates both words and images into his MLK portrait.

Haiti-themed paintings are exhibited on the other half of the gallery. His portrait of Sanite Belair is of the symbolic heroine of Haiti’s independence, a lieutenant with Louverture’s army that led to the Haitian revolution.

In his Portrait of Francois Capois: The New Revolution, the horse ridden by Capois tramples the black code while a diverse crowd accompanies him. They’re armed with books and musical instruments instead of war weapons because “ignorance and division are enemies this society must face,” Barbot writes. (In 1685, the King of France Louis XIV’s Code Noir—a document comprising 60 articles— defined the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire, activities permitted by “free Negroes,” as well as that Jews could not reside in the colonies. Capois is a leader of the Haitian revolution.)

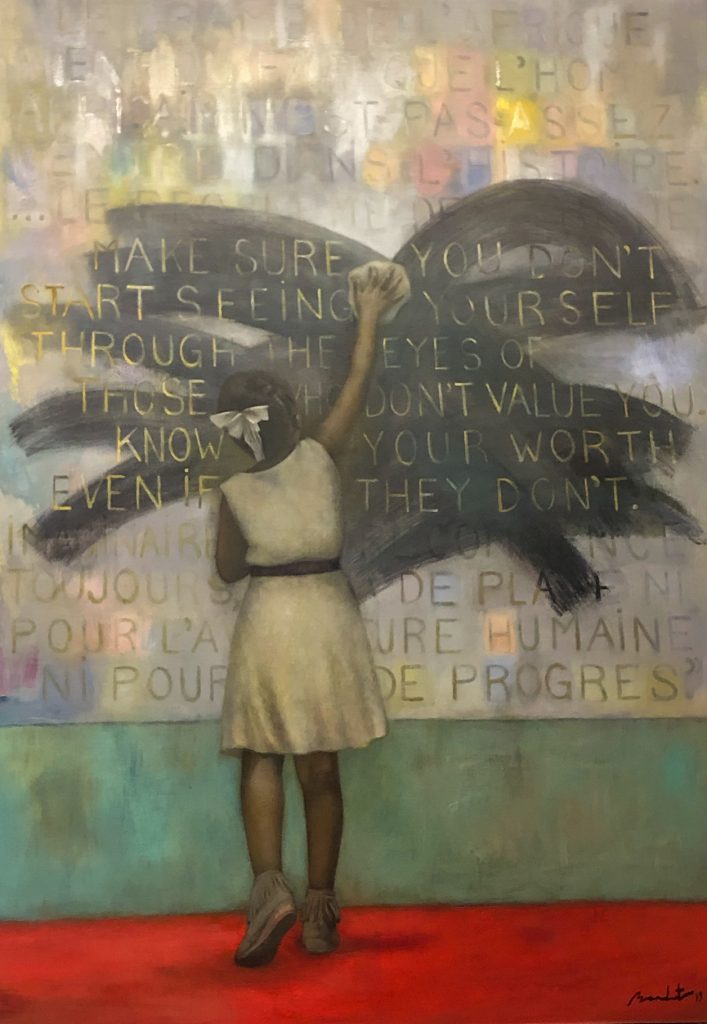

In a departure from Haiti, in his Shadow of the Past a young girl wipes away words from a speech delivered by French President Nicholas Sarkozy that characterizes Africans as being outside of history and progress. Barbot writes: To claim that “Africans have not progressed enough in the world” is to deny that Europe systematically underdeveloped Africa; colonization was brutal.

Richard Barbot was born in Port-au-Prince, lived in Montreal since childhood, drawing from a very early age. He returned to Haiti, and then back to Montreal to study art, subsequently returning to Haiti. An accomplished bass player, he also performs jazz in Haiti.

“When I paint, I like playing with shapes and colors, as a starting point,” he says. “Then like a jazz musician improvising, I try to gradually achieve a coherent image from these colored shapes.” He embraces visual influences from North America and the Caribbean, both regions where he has lived.

Bread and Roses Gallery, the only labor union gallery in the country, serves the 1199SEIU members—healthcare workers—and New York’s progressive community. Moe Foner, VP of Local 1199, founded the Bread and Roses Cultural Project in 1979.

Earlier exhibits of interest to working people included work by well-known artists like Alice Neel and Larry Rivers to works by the workers themselves—immigrant artists and international painters and photographers who were concerned with the lives of working people.

The Images of Labor iconic exhibit about what work looks like in America was accompanied by a series of posters that still remains in print. The show moved from the gallery to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Richard Barbot’s paintings are on exhibit through February. In the lobby of the Union building at 310 W. 43rd St, this is the gallery’s last exhibition at this location. 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East is consolidating offices, leaving W. 43rd St. May 1 and moving to 498 Seventh Avenue at 37th St.