By JERRY TALLMER

In Abernathy. Texas, there was once, in the mid-1950s, a 5-year-old junkie named Jay Johnson, and the junk was radio — in specific, a Saturday-morning radio show called “Big John and Sparky.”

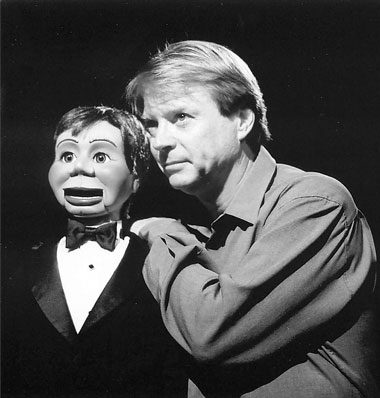

“My brother and I would lie back on our beds and listen. I thought it was two people talking, a man and an elf,” says the Jay Johnson who all these years later has arrived in New York with a small friend of his own named Squeaky.

“Radio is the perfect medium for a child,” says Johnson from the stage of the Atlantic Theater on West 20th Street. “It all happens in your imagination. Everyone looks exactly like they sound, and they sound exactly like they look. The casting is yours, the art direction is yours, and you get to see it all . . . So I saw Big John and Sparky on the radio in my mind. I see them to this day.”

But when, still as a small child, he got to see the actual Big John and Sparky in a radio studio, they “didn’t look anything like I thought they did, nothing like I had imagined.” Big John was tall, “much taller than I thought he sounded,” and Sparky was a three-foot string puppet in a little theater of his own.

Driving Jay and his brother back home from the show, their father said: “Of course you know, Big John does the voice of Sparky.”

No, until that moment, Jay didn’t know. And that moment changed his life.

At the Atlantic Theater it isn’t only Squeaky who has a running conversation with ventriloquist Johnson. There are also a talking snake, a talking vulture, a talking nutcracker, a talking tennis ball. And along the way the audience gets a bit of the history of ventriloquism, starting 805 A.D. when Plotius, a commander of the Pretorian Guard, blasted all voice-throwers as evildoers who should be condemned to dwell in a cesspool.

You can skip from there down to the Dark Ages, when public executions were served up as popular entertainment and — so we are told at the Atlantic Theater — at any handy-dandy little beheading there might be a ventriloquist waiting beside the blade to snatch up the severed but still twitching head and make it talk.

Squeaky doesn’t do anything like that, but , , , but , , ,

One of the scariest passages in film that this writer- cum-moviegoer ever saw, and saw again over the years, is the sequence directed by Alberto Cavalcanti in the 1945 “Dead of Night” in which ventriloquist Michael Redgrave loses all control over his vicious-tongued dummy.

Jay Johnson agrees.

“It’s still the most frightening thing ever,” he said last week. “Even after it was done by Anthony Hopkins in ‘Magic.’ “ With a half-laugh: “I think ‘Dead of Night’ turned a lot of people against 336 West 20th Street, (212) 645-1242.”

Say, Jay, does Squeaky ever talk back?

“All the time, all the time.”

Does he ever get out of control?

“Well, in my opinion, yes.”

Jay Johnson was born, not in Abernathy, but in Lubbock, Texas.

“Abernathy is population 2,000, now as then. When somebody’s born they have to shoot somebody so they don’t have to spend the money to change the sign. Lubbock actually has a hospital and an airport and a building four stories high.”

It was on the top shelf of his rich cousin Judy’s house — “We were about the same age, and she had every toy a boy could want” — that 6-year-old Jay discovered the Jerry Mahoney ventriloquist’s doll his parents had refused to send for from the Juro Novelty Company. Texas boys don’t play with dolls.

“I said: ‘Judy, can I play with that doll?’ She said: ‘It’s broken. It’s supposed to talk, but it doesn’t.’ I reached around to the back where the controls were. I could move the head with a stick, and here was a little ring attached to a string that opened the mouth. I had been practicing so much I knew exactly what to do. I said: ‘Judy, say hello to my friend Squeaky.’

“Judy laughed. She said: ‘How did you do that? Did you fix it?’ She took me to my grandmother, and SHE laughed. My uncle laughed. I knew at that moment I had found my drug of choice.”

When his folks felt that budding stage star Jay had outgrown Abernathy, the whole Johnson family moved to Dallas, where he went to high school, to college, and started working summers — 10 shows a day, seven days a week, 918 shows in three months — at Six Flags theme park.

But Squeaky was wearing out. “I was spending more time fixing him off stage than I was with him onstage.” In the back of a ventriloquy magazine called Oracle, Jay found a listing for a puppetmaker named Arthur Sieving, in Springfield, Illinois.

“No address, just a telephone number. So I called, and an elderly man answered the phone. I said: ‘I’m looking for Mr. Arthur Sieving.’ He said: ‘That would be me.’ We talked for an hour. I was 17, he was 71. He said he was retired and didn’t know how I’d got his telephone number, but would send me photographs of his work as a sculptor of ventriloquists’ dolls.”

The photos arrived in Dallas, and were just what Jay had in mind. “When I called back, Art told me he had already started. He’s gone now. A sweet, sweet guy. He used to say his act was very de-sieving.”

The Squeaky that Art Sieving carved for Jay way back then is the very same Squeaky who holds forth today on the stage of the Atlantic. “I’m kind of a fussbudget at keeping my puppets up,” says Johnson. “Art said he’d made something that would stand me the rest of my life, and he knew what he was saying.”

Six Flags in Dallas is, incidentally, where Jay Johnson met Sandra Asbury, the dancer from Houston, who would also share the rest of his life. They have sons 20 and 17. Future ventriloquists? “No,” says their father. “I think they’ll be musicians, writers, painters.”

He himself is an artist — “mostly sketches.” He’s also pretty well known to, well, maybe millions, as Chuck, a/k/a Bob Campbell, of “Soap,” the soap-opera satire that ran on television from 1977-1981.

When Jay was working clubs in Los Angeles years ago, another ventriloquist of some prominence on television, a fellow named Edgar Bergen, came to see that work “and was really a sweetheart to me.”

In the late ‘70S — the early days of HBO — Bergen, Shari Lewis, Jimmy Nelson, and Jay Johnson starred in a special on “The Art of Ventriloquism.”

Squeaky, shut your ears. Here is something Edgar Bergen said to Jay Johnson that Jay Johnson will never forget: “I’m certainly glad that there will be somebody to run with the football when the pass is thrown.”

Okay, Squeaky, you can unstop your ears. Don’t worry, nobody’s going to be silly enough to try to stop your tongue.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/news/bars-clubs-81/