BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | Following a meeting with senior staff at the city’s health department, some AIDS activists are saying the department never had a plan to replace the services that were lost when the agency closed its Chelsea sexually transmitted disease clinic for a two-year renovation.

“It’s public health malpractice,” said James Krellenstein, a member of ACT UP New York, following the May 15 meeting, which was convened by City Councilmember Corey Johnson, who chairs the Council’s Health Committee and represents Chelsea. “It’s like closing a firehouse in the middle of a burning neighborhood.”

Since 2007, Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen have reported the highest rate of syphilis cases in the city, with that rate being driven by new infections among gay and bisexual men. Those two neighborhoods have also reported the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses in the city, with new diagnoses among gay and bisexual men also the driver. Those neighborhoods also have high rates of gonorrhea and hepatitis C.

“The other thing we found out is that the city doesn’t have a plan to address the syphilis epidemic,” said Mark Harrington, executive director of the Treatment Action Group, an advocacy organization. “They have to have a clear syphilis response. They don’t.”

With the Chelsea clinic getting the most visits every year among the city’s nine sexually transmitted disease clinics, that facility, which closed on March 21, was expected to be a significant resource in the Plan to End AIDS in New York. That plan, which was endorsed by Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo over the past year, will reduce new HIV infections from the current roughly 3,000 annually to 750 a year by 2020.

The high volume of visits at the Chelsea clinic was an opportunity to identify LGBT New Yorkers who are candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which involves HIV-negative people taking anti-HIV drugs to keep them uninfected. PrEP is a major component of the plan.

The Chelsea clinic identified more newly HIV-infected people, called acute HIV infections, than any other clinic. People with acute HIV infections often do not know they are infected and because they are highly infectious, they make a substantial contribution to new HIV infections. Identifying those people and treating them with anti-HIV drugs keeps them healthy and reduces new HIV infections. Treatment as prevention (TasP) among all HIV-positive people, including those with acute infection, is also a major component of the plan.

“We’re going to miss a lot of people who are in acute infection and we’re going to miss a lot of people who are candidates for PrEP,” said Jim Eigo, a member of ACT UP New York.

Krellenstein said department staffers disclosed in the meeting that the closure had been planned since 2007. Department of Buildings records show that the $17-million renovation was well advanced in 2014, with the project getting nine of 10 permits approved between February and December.

The agency has placed a sign on the outside of the Chelsea clinic that refers people to its clinic on W. 100th St., and its website sends people to that other location. The health department has not responded to a request from our sister publication, Gay City News, for the number of visits to each clinic for the month of April for 2015, 2014, and 2013, so it is unknown whether the W. 100th St. clinic or any others are picking up the slack created by the Chelsea facility’s closure.

Since AIDS and community groups began pressuring the agency to replace the services, the health department has arranged for six non-profits to deploy mobile testing vans outside the Chelsea clinic location five days a week. The health department will seek $520,000 from City Hall to pay for that. Advocates said that $1 million was a more realistic number. The request for that cash will go to Lilliam Barrios-Paoli, the deputy mayor for health and human services.

Johnson said he had spoken with Barrios-Paoli, and she was supportive.

“I personally spoke with her and she is committed to getting a solution,” he told Gay City News.

The agency will also explore placing a trailer for services outside the clinic during construction, and Johnson is going to ask the city’s Department of Design and Construction, which is managing the renovation, if the job can be expedited.

Johnson was more charitable than the advocates, pointing out that, since 2008, the health department had investigated 80 alternative sites to provide services during the renovation, but none were suitable. Asked if the health department did not plan for the closing, he said, “That’s not my impression. I think the planning could have been better.”

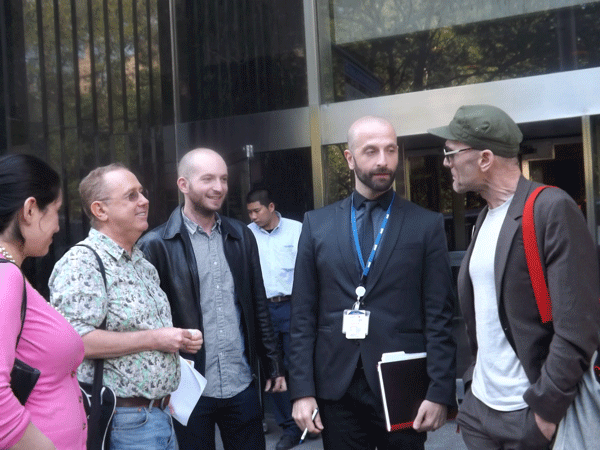

Also attending were State Senator Brad Hoylman and Assemblymember Dick Gottfried. Both represent Chelsea. A number of AIDS and health groups were also represented at the meeting, including Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Housing Works, Harlem United, the Asian Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS (APICHA), the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center.

Health department staff included Dr. Jay Varma, who oversees disease control, Dr. Sue Blank, who manages sexually transmitted disease programs, and Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, who runs the department’s HIV prevention unit. Blank and Daskalakis declined to comment following the meeting.

Johnson said the meeting was generally cordial.

“I think there were moments with it being heated,” he said. “By and large, people were trying to be practical…[The health department] was not defensive.”