BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | Adam Purple, the godfather of the Lower East Side community gardens who fought a losing battle to save his spectacular Garden of Eden from destruction for a low-income housing project, died Monday as he was bicycling over the Williamsburg Bridge. He was 84.

The cause of death was apparently a heart attack, according to Time’s Up, the Brooklyn-based cycling and environmental group that had taken in Purple in recent years.

Carmine D’Intino, a good friend of Purple’s, said the iconic activist and environmentalist — known for his flowing white beard, purple garb and mirrored sunglasses — had been biking around midday from the Williamsburg headquarters of Time’s Up to meet him in the East Village.

As usual, Purple had called D’Intino beforehand and then hung up — their signal that he was about to head out to meet him. He would have been riding a folding bike that Dintino gave him a few years ago.

“He would call me when he got to Manhattan and tell me what he was doing,” he said.

But this time, no second call came.

D’Intino had just returned from the city morgue in the E. 30s the following day when The Villager spoke with him. He said he had identified Purple’s body by an image that was shown on a computer screen.

Police did not immediately have information on what may have happened to Purple — whose real name was David Wilkie — on the bridge. A department spokesperson said they would only have a record if there had been a crime.

However, Bill Di Paola, executive director of Time’s Up, said from what he was told, Purple was found in the middle of the bridge. Passersby reportedly performed CPR on him to try to save him. Di Paola said a man he knows by his first name, Jacques, told him that he had been riding by and saw Purple on the bridge and that he did not look like he was alive. Di Paola said the bike was found next to him, though it’s possible he had been walking it — not riding it — up to the middle part of the bridge.

Di Paola said Purple would take his bike over the bridge and into the East Village about twice a month to shop for food at Commodities Natural Market, at E. 10th St. and First Ave.

“I think the summer took a toll on him because it was very hot,” D’Intino said. “He was living in a little room at Time’s Up. He was thinking about moving in with me.”

Di Paola said Purple had been living at Time’s Up for the past three years, in a small room located off the bike-shop work area.

“He really had no place else to go and he liked Time’s Up,” he said. “Being around our bike shop and energy really energized him.”

In a statement, Time’s Up said, “Yesterday, we lost one of New York’s most well-known and colorful environmentalists. We also lost one of Time’s Up’s oldest and most dedicated volunteers.

“We all knew and loved Adam. His commitment to a sustainable lifestyle was unrelenting and all-encompassing. The community garden that he created with his own hands was so lush and grandiose that even NASA saw it — from outer space! Appropriately, it was called the Garden of Eden.”

Purple helped with day-to-day operations and night management at the space. Di Paola said Purple helped sort parts and assisted during their recycle-a-bike workshops.

In a feature story two years ago about Purple hanging out with the younger cyclists, the Daily News dubbed him the “Original Hipster.”

David Wilkie — who would later become Adam Purple during the psychedelic era — was born in 1930 in Missouri. Purple would always tell The Villager how he had been a police reporter for newspapers. According to D’Intino, he was also an English teacher and was drafted during the Korean War, but was given a special noncombat post.

As for how Purple got his nickname, he once told The Villager it came from “the magic mushroom.”

He also went by some other monikers, including General Zen and the Rev-Les Ego.

Last Thursday, D’Intino met with Purple at the Time’s Up space and they spoke about getting in touch with the elderly activist’s family members and putting his papers and archival materials — including about his beloved Garden of Eden — in the right hands.

According to D’Intino, Purple’s survivors include a son, about age 30, who teaches English in Japan; a grandson who is in publishing in California; and several daughters. The grandson republished Purple’s miniature-size book of koans, “Zentences,” which is included in the New York Public Library’s Rare Books Department.

His former wife — who was known as Eve — is probably still alive, according to D’Intino, though he said Purple “didn’t like her because he got locked out of an apartment by her and a lot of his personal possessions got taken away.”

Di Paola said he spoke to the police detective on the case, who told him they were having trouble tracking down Purple’s family members to notify them of his death.

D’Intino added that Purple was “old-fashioned” and often carried a lot of money on him, and that he could well have had a substantial amount of cash on him when he died.

At one point, Purple had a cult following. His devotees — who were vegetarian, like him, and did not wear any leather garments or leather shoes — were known as the Purple People.

As for how D’Intino met Purple, he said he was walking down the street nearly 30 years ago and started talking to the hirsute hippie gardener. Purple, however, told D’Intino he needed to “learn” a few things about how to talk first, and that they would converse again later.

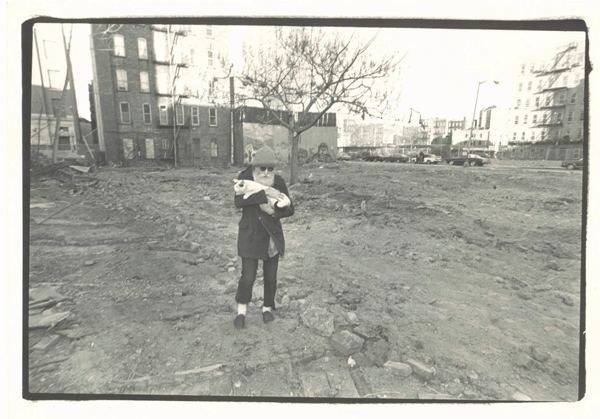

Purple’s garden was demolished in 1986. The fight had become so heated that, as The Villager reported back then, future Councilmember Margarita Lopez had fumed she would tear the green oasis down with “my bare hands” if she had to.

“He had been knocked out of the garden,” D’Intino recalled. “He was depressed for about a decade. He had a court order saying they couldn’t destroy it —but they destroyed it anyway.”

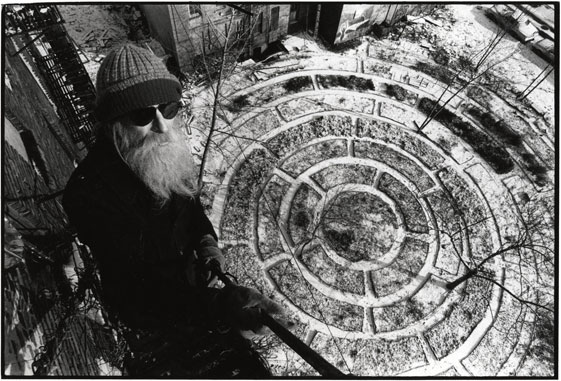

The Garden of Eden covered 15,000 square feet between Forsyth and Eldridge Sts. near Stanton St. With planting beds in Zen-like concentric circles, it featured corn, cucumbers, tomatoes, asparagus, raspberries and 45 trees.

“It was a work of art — an earthwork, a work of art that was also ecologically based,” Purple told Amy Brost in a 2006 interview.

Adam and Eve would bike up to Central Park to collect horse manure and bring it back to fertilize the garden’s soil.

Regarding how Purple came to live in his Forsyth St. building, D’Intino said it was because he had first been the super there, but it was then abandoned by the landlord. Purple continued to reside in the old tenement without electricity or any services, before it was ultimately demolished by the city around the turn of the century to make way for housing for the deaf. According to D’Intino, Purple was compensated $10,000 by the city after the building was taken from him.

Di Paola recalled how Purple’s bike would have bells on strings hanging down from the handlebars, and that to ring them, he would have to shake the whole bike.

The cycling activist also remembered how, back when he was living on Broadway at Astor Place, he stepped out of his building only to find a wiggling path of purple footprints on the sidewalk. These had been made by Purple’s friend George Bliss, who wheeled a drum-barrel contraption with purple paint inside of it to create them. The prints led back to the the site of Purple’s destroyed garden.

“And Adam was on Regis and Kathy Lee talking about the garden,” Di Paola added. “I think George was there and he was wearing a mask — it was like a beehive.”

In more recent years, Purple could sometimes be spotted biking around the Lower East Side collecting cans.

“His paradigm, it was antithetical to the modern paradigm,” D’Intino said, “which is just to pave over all the green spaces.”

Sometimes D’Intino would drive Purple into the city. But his friend said the nonagenarian never liked it, since he was “anti-the internal combustion engine.”

D’Intino said that last Thursday when he met with Purple at the Time’s Up space to discuss his estate, the legendary environmentalist gave him a very warm embrace — which was unusual for him.

“The last time, he was very physical and hugging me,” he said. “Usually, he was austere, intellectual.

“He said he’s not going to make it to see the water rise up a couple of feet in the neighborhood.”

A memorial for Purple is planned for Sat., Sept. 26, from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m., at La Plaza Cultural, at the southwest corner of E. Ninth St. and Avenue C. People are invited to speak briefly and share their memories. Further details of the memorial were still being worked out.

Di Paola said that when the city was about to demolish Purple’s building, he and others briefly went inside it with the idea of occupying it in a last-ditch effort to save it.

“On the first floor, all the beautiful purple tie-dye clothes were hanging up and there were his diaries,” he said. “The diaries were fascinating: On one day he’d be collecting horse manure and the next day he’d be on Regis and Kathy Lee. That was his life. I wish we had taken them.

“We didn’t get to preserve his diaries, but Time’s Up played a part in preserving him as a living legend.”