BY NORMAN BORDEN | Before West Chelsea became an art district dense with over 300 galleries, and even longer before an elevated public park would once again transform the neighborhood’s relationship with tourism and foot traffic, The Half King bar and restaurant opened on a deserted stretch of W. 23rd St. — which now happens to be less than 100 feet from an entrance to the High Line.

When it was established in July of 2000, the three co-owners — journalists Scott Anderson and Sebastian Junger and filmmaker Nanette Burstein — had envisioned Half King as a neighborhood place where members of the publishing and film industries could meet and talk shop. By the fall, weekly non-fiction readings on topics of interest to the co-owners had been added to the menu, along with a rotating schedule of photography exhibitions.

“Sebastian and I had done a lot of war reporting,” Anderson recalled, “and we’d both worked with some pretty amazing photojournalists over the years… I recognized there was a limited number of outlets where they could show their work.” So Half King became “one of few venues where straight-ahead photojournalism can be displayed,” he said, noting that the forum they provide “allows the photographer to show their work largely among their peers, and is a great opportunity for photojournalists to get together and see what others are doing.”

Writer and editor Anna Van Lenten and James Price (an editor at Getty Reportage) were hired as co-curators in 2010, to make the photography series more consistent. As a result, Half King is operating on a “strict schedule now,” Van Lenten said, with new shows every seven or eight weeks. “We’ve standardized the frame sizes (32 x 23 inches) and operate like a gallery/salon, even though we don’t look like one.”

That’s for sure — the 11 photographs in each show are displayed along the walls of a separate dining room that seats 50, and is closed off from the bar and other diners.

The openings are meant to be super focused discussions around the story or book launch, very casual and intimate,” Van Lenten explained. “We turn off the lights and do a slide show that lasts from 45 to 90 minutes and encourage the audience to ask questions. We show narrative photography. They’ve spent years immersed in stories they bring to us; they’re quite intense, and know their subject top to bottom.”

In her ongoing search for future exhibitors, Van Lenten asks other photographers to recommend people they like. She also pays attention to award shows, Facebook and Instagram, and she subscribes to lots of newsletters. In any case, “The bar is high. The work has to be beautiful and visually distinctive; the story has to be compelling either because the photographer took an alternative approach or had an interesting evolution; and the photographer has to speak English well enough to give a talk on opening night.”

One excellent example of Van Lenten’s credo is the current exhibition: “Family Matters,” by Mexico City-based photographer Adriana Zehbrauskas. It’s a bittersweet story that began when 43 male students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College in Guerrero, Mexico disappeared on September 26, 2014, taken by the police and then handed over to a narcotics gang. The photographer had been working on assignment with one of the families and had asked for photos of their missing brother. There were none — all they had were cellphone photos that could be accidentally deleted or lost if the phone was changed. Since nobody printed pictures, she realized these families could suffer another loss — the memories of their missing loved ones.

Zehbrauskas decided to start a personal project where she would take family portraits for free and hand out the prints on the spot. Shooting “Family Matters” called for driving eight hours back and forth from Mexico City to Huehuetonoc, Guerrero, going through dangerous narcotics gang-controlled territory. Having worked in the area for 10 years as a freelance documentary photographer, she said, “You have to stay alert for kidnappings and shootings.”

In the town, Zehbrauskas set up a table by the church where family members could meet her for their free pictures and people could clearly see what she was doing — taking portraits with her iPhone and using a small Canon printer to produce the photo on the spot.

“I’ve taken lots of photos,” Zehbrauskas said. “Eighty portraits on my first trip in 2016, and I also give my subjects large prints on my return trip from Mexico City. I’m paying my expenses with a Getty Images Instagram grant I was awarded in September 2015 to document under-represented communities. I upload this work on Instagram and also publish on the New Yorker Magazine’s live feed.”

At the exhibit’s opening on May 24, it was standing room only as Zehbrauskas showed about 40 images in a fascinating hour-long slide presentation. Her comments added a greater understanding and deeper appreciation of the project and its challenges. Her talk also demonstrated the unique opportunity that photojournalists from around the world have to show and discuss their work.

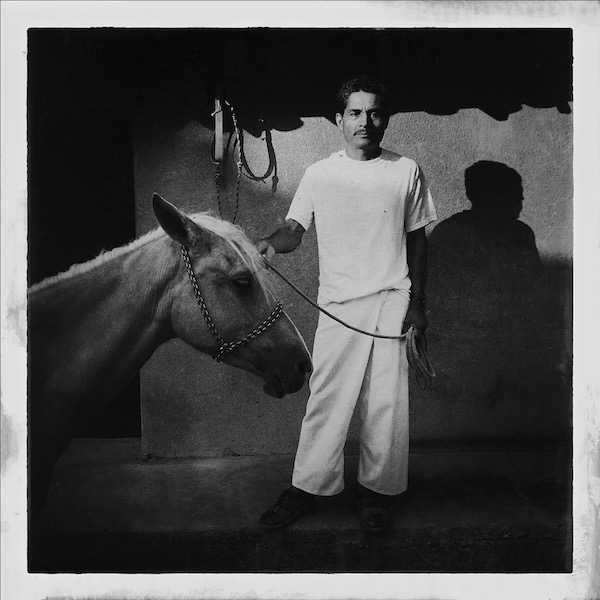

In my view, many of the 11 images in the exhibition can be considered to be in the realm of fine art photography. One outstanding example on view now is “Don Gerardo and La Rubia.” I see this photo as an intimate portrait of a man and his friend, a horse — the composition, lighting, and the print are all beautiful, as are the subjects themselves.

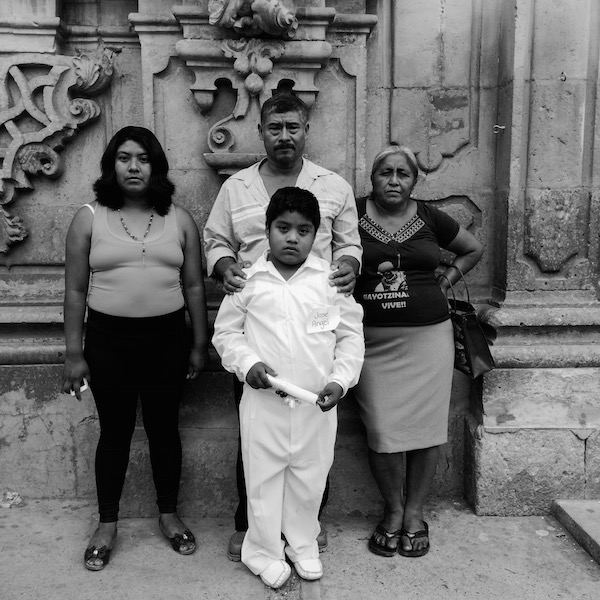

Also impressive was the portrait of “The family of Adán Abraján de la Cruz.” Adán was one of the 43 missing students. This photograph was taken after the First Communion of Adán’s eight-year-old son, Angel, in Tixtla, Guerrero. You not only see the sadness in this photograph, but also feel it. Angel’s mournful, wistful look is haunting, reinforced by his mother and Adán’s parents standing with him.

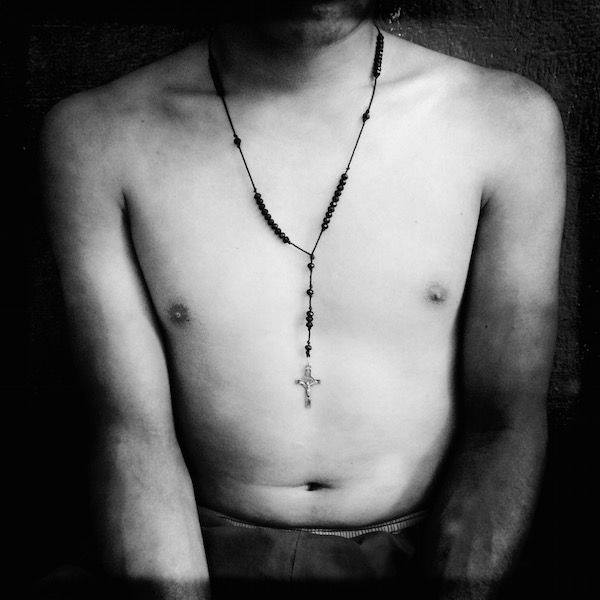

Another photograph, the faceless portrait of 19-year-old Xalpa, is a powerful reminder of the students’ disappearance on the night of September 26. Xalpa was one of the survivors and understandably didn’t want his face shown. You can only imagine what he saw and the pain he feels now. Sadly, there are many more stories of missing people in Mexico, and Zehbrauskas hopes her continuing work on “Family Matters” will help keep the families of the victims from feeling abandoned.

With stories like these, The Half King Photography Series has more than fulfilled the co-owners’ original intent. As for the future, Anderson said that changes in the neighborhood (most notably, rent increases) have made it “increasingly difficult for a small business to operate. We’ve had a good run. Our lease is up for renewal in 2019, so we’ll have to wait and see what happens.” In the meantime, there are burgers, beer, and plenty of food for thought at The Half King.

Adriana Zehbrauskas’ “Family Matters” is on view through July 17 at The Half King (505 W. 23rd St., btw. 10th & 11th Aves.). Hours: M–F, 11am–4pm; Sat. & Sun., 9am–4pm. Visit thehalfking.com and halfkingphoto.com or call 212-462-4300. Twitter: #hkphotoseries.