By Albert Amateau

Sy Weinstein, who led Army Air Corps photography units in Italy and France during World War II, has a lot of memories to share this Memorial Day — memories of seeing a ship carrying his best friend explode and sink in the Mediterranean, memories of a French girl who guided him through a minefield on a rescue mission, memories of Italian and French villages devastated by war and a harrowing memory of a visit to Dachau.

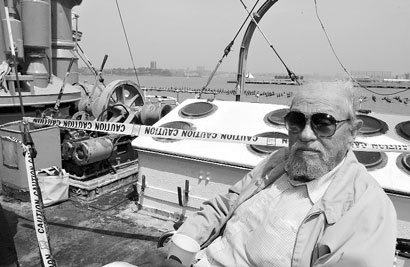

Weinstein, 86, a resident of the Hallmark in Battery Park City, is going to Washington, D.C., Memorial Day weekend to preside at the opening of “Reconnaissance and Recollection,” an exhibit of photos produced by his unit — including many images of civilian life in war-torn Europe that he took himself.

A repeat of his autumn 2003 exhibit at Bnai Zion House on E. 39th St. in Manhattan, Weinstein’s exhibit at the National Museum of American Jewish Military History in Washington will open on a weekend that includes the dedication of the National World War II Memorial on the Mall in Washington.

At an interview this week in his Hallmark apartment — decorated with his paintings, photos and models of World War II airplanes — Weinstein reflected on the chain of wartime events and coincidences that shaped his life.

“One of my closest friends in the 485th Bomber Group was a flight surgeon, Stanley Snitow,” Weinstein recalled.

“The day before we were to sail for Italy on the same ship, a colonel on another Liberty ship, the Paul Hamilton, became sick and Stanley was transferred to the Hamilton to take care of him. I tried every which way to get on the same ship, but there was no room — they had to put a cot in the colonel’s room so Stanley could stay with him. We went over in the same convoy and when we entered the Mediterranean a German torpedo plane hit the Hamilton. I was standing on deck and saw the ship blow up and sink — every man on board, 600, were lost,” Weinstein recalled.

After the war, Weinstein went to call on the Snitow family and met Dorothy Rosenberg, Stanley’s cousin, who became his wife and the mother of their two sons. She died 10 years ago.

Another fateful event was at Haguenau in France, where Weinstein was the head of the Second Technical Photographic Unit of the Ninth Army Air Corps.

“We heard explosions and screams from a bunch of my men who had gone on a picnic with their girlfriends and got into a minefield,” Weinstein said. “I got some guys together to bring them out and a little French girl, 16 years old, told me she saw the Germans laying the mines and thought she could remember where they were. She led us into the minefield and we got most of the people out. She saved my life,” he said.

The Army decorated Weinstein for bravery in the minefield incident and the French government gave the girl, Cecile Wendling, a medal. “I got a citation for saving people’s lives, not for killing anyone. I’m glad about that,” he said. Weinstein and his family have visited Cecile and her family several times over the years. He’s also made frequent trips with his family to Italy, where he made many friends during his service there.

“When we got to Dachau, I couldn’t do any of the photography myself. It was too gut-wrenching,” Weinstein, who is Jewish, said. “I had to get out of there. I really ran away.”

Born in Brooklyn, Weinstein studied art and art education at Brooklyn College and at Columbia Teachers College. He was a substitute art teacher at Erasmus Hall High School when he was drafted soon after he turned 22. Stricken by polio when he was a child, his leg muscles were atrophied, but he was able to walk unaided and the Army put him on limited service in the Air Corps. Now he uses a walker to get around and a wheelchair for longer trips.

“I was an art teacher, so they sent me to photo school — the closest thing to art that they had — at Lowery Air Base in Denver,” Weinstein recalled. After six months, he became an instructor and eventually made the rank of staff sergeant. “I came up with a concept for teaching bomber gunners how to identify enemy planes. We were using flash cards but I put a shutter on a projector that let us control how fast we changed the images. We got them to recognize planes almost instantaneously, in 250th of a second,” he said.

After three years, the Army sent him to officers training at Yale. “A lot of the guys I taught at Lowery wound up being my instructors at Yale,” he recalled. As a second lieutenant, he was sent to Venosa, Italy near Naples in 1943 to run a photo unit for B-24 Liberator bombers.

Weinstein was in charge of supplying and maintaining cameras, making sure crews knew how to operate them and developing and printing combat and reconnaissance film when the crews returned from their missions. “I had my own jeep and I was able to ride around the country and take pictures of civilians in small towns and farms. Any American in uniform with a camera attracted kids and families. I got to know a lot of people and made many friends in Italy — I love the country,” he said.

Weinstein made occasional flights to make sure bomber crews were using the cameras correctly. “They let us go on milk runs, nothing very dangerous,” he recalled. Weinstein also had to take photos of bombers that crashed on landing or take-off. He said he still remembers terrible sights of airmen emerging from crashed planes missing limbs.

In July 1944, a few weeks after the Normandy invasion, Weinstein was transferred to a photo unit with the forces preparing to land in southern France. “We landed east of Marseilles two days after the first wave, and it seemed there wasn’t a shot fired. There was no opposition and we didn’t stop until we got to Haguenau, near Strasbourg,” he said.

The unit then went to Sandshoe, Germany, where it was in charge of low-altitude photography. Weinstein made several flights in modified P-38 fighters to take aerial photos of ground installations. “We went nose down to take shots but it felt like the ground rushing up instead,” he recalled.

At the end of the war, he was assigned to teach art to G.I.s in Paris. It was there that he met the renowned French Expressionist painter Georges Rouault. Weinstein showed Rouault some of his paintings and was invited to paint in Rouault’s studio. “He was a great artist and a great guy,” Weinstein remembered.

Art and photography run in the Weinstein family; his older son, Gerry, is a photographer who has had several shows. Gerry also runs the family’s instrument manufacturing firm, General Hardware, located Downtown in Tribeca. Weinstein’s younger son, Martin, is a painter who runs the not-for-profit Art In General gallery, also in Tribeca.

“When I came back from Europe after the war, I was able to save about 2,000 negatives which were going to be dumped,” Weinstein said. Those images, preserved and organized by Gerry Weinstein, are the source of the exhibit that opens in Washington, D.C. this week. A small part of those images is also in the permanent exhibit of the Bnai Zion House gallery at 136 E. 39th St. near Lexington Ave.

Albert@DowntownExpress.com

WWW Downtown Express