BY ALBERT AMATEAU | The two burial vaults with coffins and scattered skeletons that construction crews discovered under the street on the east side of Washington Square Park on Nov. 3 and 4, reminded Villagers that much of the park served as a paupers’ cemetery during the first two decades of the 1800s.

“To this day the remains of more than 20,000 bodies rest under Washington Square,” said Emily Kies Folpe in her book “It Happened on Washington Square,” published in 2002.

“From time to time, bones have resurfaced,” said Folpe in the potter’s field chapter of her fascinating history of Washington Square Park and its environs.

An 1848 guidebook noted that bones from the field had been “collected in vast trenches on either side of the square and planted over with trees.”

And in 1890 workmen digging the foundation for the marble Washington Arch came upon headstones dated to 1803 with German inscriptions. The headstones were thought to be from a private German graveyard at the north side of the field.

Indeed, the burial vault that was uncovered Nov. 3 on Washington Square East near Waverly Place was actually a rediscovery. Folpe noted that in the summer of 1965 Con Edison workers broke through that burial chamber while digging a 12-foot shaft for an electrical transformer. Twenty-five skeletons were jumbled in a corner of the 15-foot-by-20-foot chamber, which was 14 feet tall, the arched roof of which was 5 feet beneath the surface of the street, Folpe wrote. Con Edison closed the shaft and filled the hole, and the incident was apparently forgotten for 50 years.

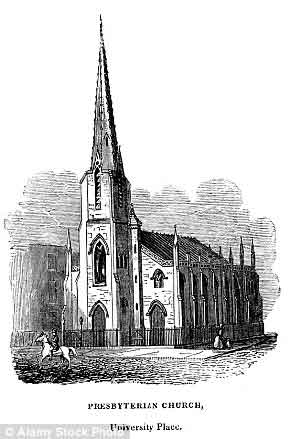

Some of the land on the east side of the burial ground, which opened in 1800, had been a fenced-in cemetery of the “Scotch Presbyterian Church” located in Lower Manhattan. The city Common Council compensated the church for taking over their cemetery, but the church elders said it was not enough. The Council reassured the church in a document saying, “It is not the intention to disturb the ground that is within the graveyard nor will there be any absolute necessity for such a measure.”

Workers at the trench on Washington Square East earlier this month, a few days after the two old burial vaults were found.

Nevertheless, the church dug up the remains and transferred some of them to the new potter’s field.

The need for a potter’s field at what is now Washington Square became pressing around 1797 when a wave of deaths from a yellow-fever outbreak overwhelmed the old potter’s field at what is now Madison Square Park. In a complex real estate transaction, the Common Council bought the land bounded on the west by Minetta Brook and on the east by Margaret St. (which became Washington Square East) for 1,800 pounds sterling.

It wasn’t an easy deal.

Wealthy New Yorkers, including Alexander Hamilton, had built summer homes north of the swampland around Minetta Brook. They fired off a letter to the Common Council protesting a potter’s field “in the neighborhood of citizens who had at great expense erected dwellings on the adjacent land for the health and accommodation of their families during the summer months.”

The letter also noted the rapid growth of the city and predicted that the field would “in the course of a few years be drawn within a precinct of the city.”

The Common Council found a possible alternate site, but a vote on the matter was tied, leaving Mayor Samuel Varick to cast the deciding vote in favor of the original location.

By 1798 about 2,000 New Yorkers had died of yellow fever, about 660 of whom were buried in the new potter’s field.

About 150 years earlier, the Dutch West India Company’s New Amsterdam settlement had been threatened when relations with the Lenape, the local Native Americans, turned violent. Farmers in what is now Greenwich Village (Noortwyck, to the Dutch) fled behind the Wall St. palisade.

Willem Kieft, the director of the colony, solved the problem by freeing some African slaves and granting them the abandoned farms, to serve as a buffer between the natives and the settlers.

It wasn’t such a good deal for the freed slaves.

They had to pay 22 bushels of any two crops that they grew and a fat hog every year to keep their freedom. And worse, their children — even those born in the future — remained slaves of the company.

The first farm grant went to Catelina Anthony in July 1643 for eight acres around what is now Canal St. and Broadway. North of there, Manuel Trompeter received 18 acres in December of that year. On Sept. 5, 1645, a grant went to Anthony Portuguese for a piece of land in the marsh around Minetta Brook, marked as Bestavers Rivulet on early maps. The name Portuguese indicates that Anthony came from the Portuguese colony of Angola in West Africa.

Freed slaves were farming about 300 acres in Manhattan by the end of the 1600s. But by the mid-1700s they had lost their lands to British and Dutch neighbors.

Between the opening of the potter’s field in 1798 and the last burial in April 1825, it was the place for other lugubrious events.

It was where people convicted of crimes and sentenced to death were hanged from temporary scaffolds. The superintendent (and gravedigger) of the potter’s field served also as the hangman. Contrary to reports in the 19th century and contrary to belief popular even today, no one was ever hanged from the huge 300-year-old elm tree that still stands near the northwest corner of Washington Square Park.

The last person hanged in the square was Rose Butler, a young black woman convicted of setting fire to the house where she worked. The hanging, on July 8, 1819, was delayed several days in the hopes that she might reveal any accomplices to the arson. But she never confessed to setting the fire, which might well have been an accident.

The square was also a “field of honor” where bellicose gentlemen fought duels to settle disputes and redress insults.

In 1803, William Coleman, editor of Hamilton’s New York Evening Post and a staunch Federalist, was killed in a duel with Captain Thompson, the harbormaster of the Port of New York and a partisan of Aaron Burr’s Democratic-Republican Party. The duel over an insult arose out of their political rivalry. Two months later, Burr killed Hamilton in a duel in Weehawken, N.J.

Another wave of yellow fever swept over the city in 1822 adding more bodies to the square. By 1823 the burgeoning city ordered that surplus earth from development on the north side of the square be moved to fill in the burial ground, which had sunk below the level of adjacent streets. That project marked the filling in of Minetta Brook and its subsequent underground course.

By 1824, the burial ground was nearly full and no more interments were allowed after May 1, 1825.

By then, the growing city had overtaken the neighborhood and a new potter’s field was established between Fifth and Sixth Aves. at 40th and 42nd Sts., the present location of Bryant Park.

Meanwhile, the former burial ground was converted amid great pomp and ceremony to a military parade ground. The Common Council approved the change in February 1826, giving local militia a place to drill and show off their uniforms and equipment.

The new Washington Military Parade Ground was formally opened on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

In a conversation with The Villager last week, Folpe, who lives a block north of the park, recalled the genesis of “It Happened on Washington Square,” which covers the history of the 9.75-acre park from the very beginning to 2000.

An art historian who teaches at New York University and has lectured at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Folpe became active in neighborhood and park issues in the late 1990s, when she joined the Washington Square Association and spoke with Village advocates, among them the late Tony Dapolito and other members of Community Board 2.

The book took more than a year to complete and then more than another year getting ready for publication, entailing a search for maps and photos and the rights to include them in the book.

Would she undertake the same kind of effort for a different subject?

Folpe told The Villager, “It was very exciting, but for days on end I didn’t see or speak to anybody —sometimes in the dark reading microfiches in the city archives. I really like people, but I guess if another subject grabbed me, I would do it.”