BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Facing a room packed with Village residents, David Gmach, director of public relations for Con Edison, had the task of explaining to them why the power went off in most of Lower Manhattan during Superstorm Sandy and why it stayed off for days thereafter.

During Hurricane Irene, there were around 200,000 power outages, he said, out of around 3.1 million customers in the five boroughs and Westchester County. Before Sandy, this was the worst situation that Con Edison had ever encountered. During Sandy, there were 1.1 million customer outages.

Gmach, addressing a meeting of Community Board 2’s Environmental Committee, told his audience that out of the 1.1 million Con Ed customers who lost service, around 230,000 were in Manhattan. Most were south of 40th St. on the East Side and south of 30th St. on the West Side. That would have included most of the people in the room.

Gmach said that Con Ed had prepared for flooding but not for the height and power of Sandy.

“The prior record for a storm surge was in the 1820s at around 11 feet hitting New York Harbor,” he said. “The forecast that everyone was talking about up until just before [Sandy] hit was maybe reaching that level, maybe exceeding it slightly at about 12 feet.”

The surge from Sandy was 14 feet — “2 to 3 feet higher than anything that had happened before and 2 feet higher than what anyone had forecast,” Gmach stated. “So this was flooding on a level that had not been predicted and was much worse than anything we had seen.”

Actually, however, a storm surge as devastating as Sandy had been predicted, and by some of the people who were in the room that night.

Since 2009, Robert Trentlyon, former publisher of Downtown Express, The Westsider and Chelsea Clinton News, had been talking about just such a possible storm surge, but few people were listening. Contemplating the effect of global warning, Trentlyon had come to the conclusion that a massive flood in New York City was inevitable. Along with Malcolm Bowman, chairperson of the Oceanic and Atmospheric Department at Stony Brook University, and Douglas Hill, an engineer with expertise in oceanography, Trentlyon went to numerous political and city planning meetings, expounding on the problem and recommending storm surge barriers in New York Harbor as a possible solution.

“I spoke out,” said Trentlyon, “but got minimal positive response.” However, gradually that began to change. City Council Speaker Christine Quinn got onboard. So did U.S. Representatives Jerrold Nadler and Carolyn Maloney, New York State Senators Daniel Squadron, Tom Duane, Brad Holyman and other elected officials.

“Now,” said Trentlyon, “New York City has hired Jeroen Aerts of the University of Amsterdam to give an appraisal of our entire waterfront, which should be completed this summer.” He also said that Governor Andrew Cuomo, Senator Chuck Schumer and Speaker Quinn had spoken in favor of having the Army Corps of Engineers study storm surge barriers, among other proposals for protecting New York City.

“Not bad,” said Trentlyon wryly, “for three years of work against a recalcitrant city government. We should not forget Irene and Sandy, who unfortunately gave this effort a much-needed push.”

Professor Bowman, who has been talking about storm surges and what they could do to New York City even longer than Trentlyon, also addressed the Community Board 2 audience.

He said that in 2005, he had written an op-ed piece for The New York Times that he wanted to call, “New Orleans has just drowned. Is New York City next?”

The New York Times editors told him that title was too provocative, he said.

“They told me, ‘You can’t say things like that!’”

Bowman said, “The bottom line was it’s not a question of if, but a question of when New York City is going to get flooded.”

He described watching Hurricane Irene approach New York City, and measuring the water levels of that storm against a nor’easter in 1992 that had flooded the Hoboken train terminal and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. As the water level from Irene began to rise, he thought the flooding was about to happen again.

“It came within an inch and a half of what it was the night Hoboken flooded,” but then receded, he said. “When I talked to city officials they said, ‘We dodged that bullet, life goes on, stop worrying about it.’ ”

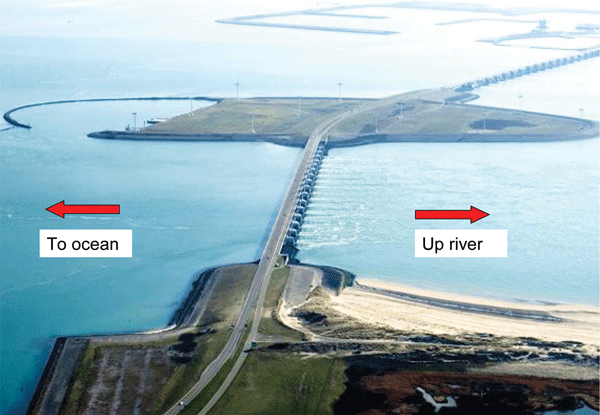

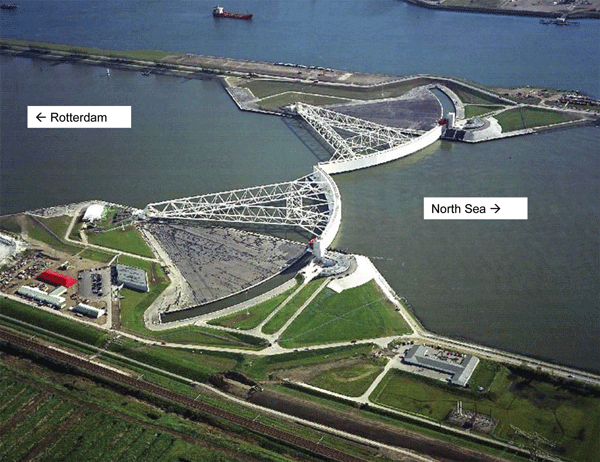

Now everyone is worrying and looking for solutions. Bowman pointed to storm surge barriers that have been successfully installed in other cities in other countries — most notably in London, St. Petersburg, Russia, and in the Netherlands.

He explained that these barriers allowed for commercial shipping and for the flow of tides necessary to flush out their respective harbors, but had gates that could be closed in case of an emergency.

For New York City, Bowman said, one proposal would be to build an elevated highway similar to the one that protects St. Petersburg and extends into the Baltic Sea, with storm surge gates that could be lowered from the highway when needed.

“There are various ideas as to where the gates should be positioned and what they would look like,” Bowman said.

He emphasized that at this point this and other ideas are just exploratory.

“No one suggests that anyone is going to start pouring concrete next week,” he said. “These designs are in the conceptual stage. If the state got serious about regional protection — not instead of, but in addition to the resilience strengthening we have to do — then the Army Corps would have to be brought in to do a major study. It might take five years looking at all the pros and cons of barriers if we’re going to build them. Where would they have to be? How high would they have to be? What would be the construction materials? What would be the effect on the tidal circulation, the flushing, the fisheries, the water quality? And then there are legal questions, social justice questions. The list goes on and on.”

Bowman said that in Europe, it took 20 to 25 years of study before the barriers were built.

However, he added, “We do have barriers already. We have a set in Stamford, Connecticut, that were used during Sandy and the city had no damage whatsoever. We have them in Providence, Rhode Island, and in New Bedford, Massachusetts.”

Do we have any idea how much these barriers would cost to install in New York Harbor? one member of the audience wanted to know.

“Yes,” said Bowman. “Around $26 billion, including the cost of shoring up the areas on the sides of the barriers — far less than the cost of the damage inflicted by Superstorm Sandy.”