The Peebles Corporation and Elad Group wanted to gut the mechanical clock atop 346 Broadway and turn the space into a grand penthouse. The Landmarks Preservation Commission signed off on the plan in December 2014, but a Supreme Court judge overruled it on Mar. 31.

BY YANNIC RACK

The bell has tolled for developers’ penthouse plans involving the historic clock atop a landmarked Tribeca building.

A judge ruled last week that the owners of 346 Broadway can’t replace the ancient mechanism inside the building’s clock tower with an electric motor to make room for a triplex penthouse.

Manhattan Supreme Court judge Lynn Kotler overruled a controversial 2014 decision by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission on Mar. 31, delivering a huge win to preservationists who had fought a legal battle to keep the 119-year-old clock at 346 Broadway from going silent.

“In a world where developers run our city in a kind of tragic oligarchy, it is nice to be reminded that justice against the developers can sometimes still prevail,” proclaimed a statement from the Tribeca Trust, one of the plaintiffs that filed the lawsuit against the developers and the city.

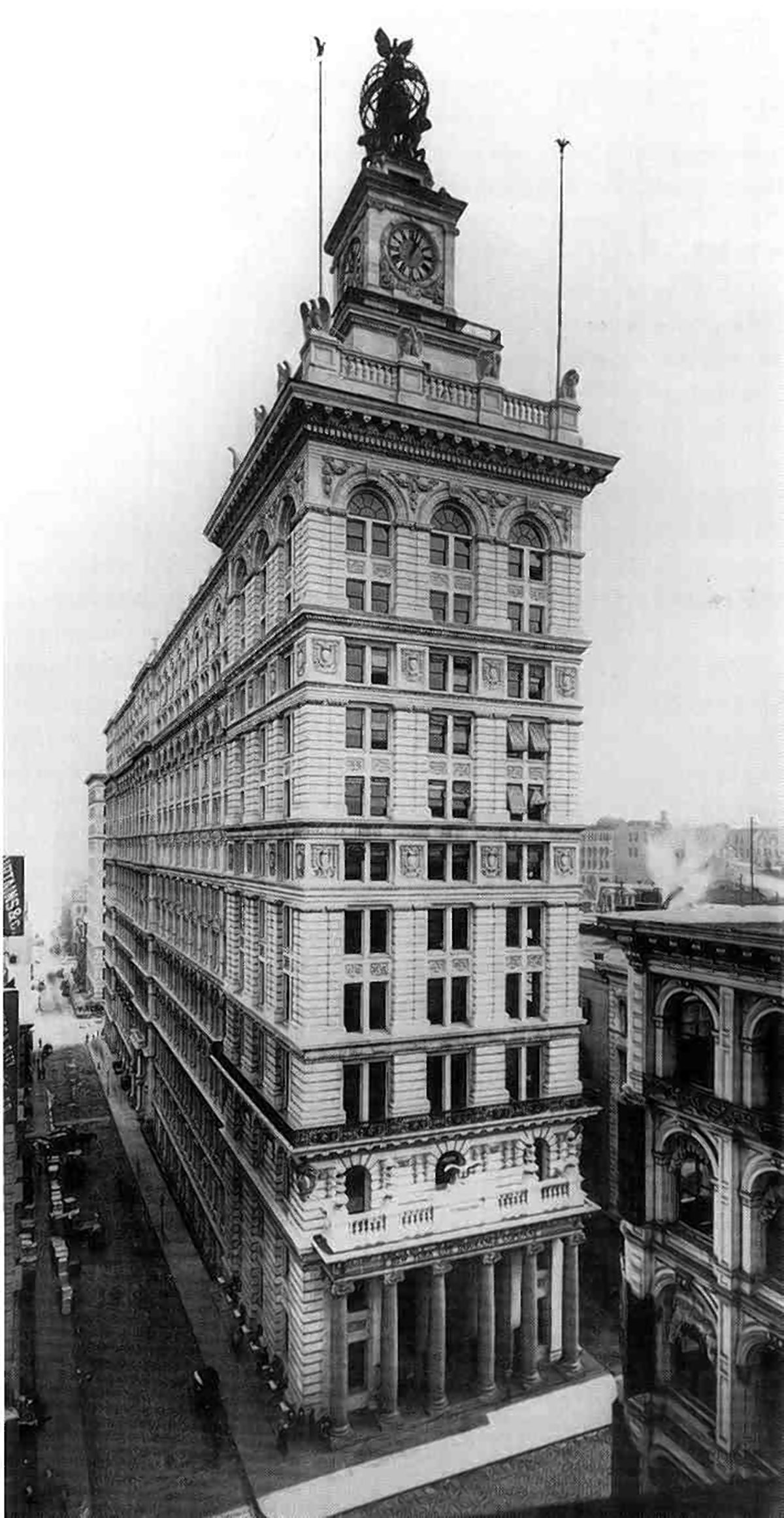

The controversial chronometer sits atop the 14-story former New York Life Insurance Company Building, which the city sold to the Peebles Corporation and Elad Group three years ago.

The owners announced in 2014 their plans to convert the landmark into luxury apartments, and after a contentious hearing the landmarks panel issued a certificate of appropriateness for the project, which included renovating the clock-tower suite and electrifying the clock — whose ancient mechanism has been hand-wound by a city-appointed “clock master” for decades.

Marvin Schneider, a former city employee who has operated and maintained the clock once a week for the past 35 years — until the developer locked him and his colleagues out of the building last spring — said the ruling was a huge victory.

“I’m thrilled that the judge came out with this decision, and I feel vindicated,” Schneider said after the ruling, adding that he advocated for the building to be landmarked in the mid-1980s because he expected exactly this kind of scenario. “I anticipated something like this happening many years ago. My concern was, should the city sell it at some future date, what protection would there be? And I found out that even if something is a designated landmark, there’s no guarantee.”

In 1987, the commission landmarked the exterior of the building and also designated parts of the 13th and 14th floors, including the clock machinery, as an interior landmark. At the LPC meeting in 2014 when the condo conversion was approved, the commissioners reached the conclusion that, while they had authority to ask the developer to keep the clock in operation, they had no power to mandate how.

“There’s nothing in the landmarks law that requires or gives the commission the power to require that this mechanism remain operable,” the commission’s general counsel, Mark Silberman, said at the time, according to The New York Times. “Whether it’s electrified or someone is allowed to wind it, that is not something the landmarks commission can require.”

But the judge annulled parts of the certificate in her ruling last Thursday, calling the LPC decision “irrational and arbitrary.”

“There can be no dispute that the internal mechanism by which the clock operates is a significant portion of the clock itself,” Kotler wrote in her decision. “If the commission can issue a violation for its removal or alteration, the legislature [also] intended to give the commission the power to compel the owner to maintain the clock’s mechanical operation.”

She also said the tower should remain accessible to the public, calling access “a specific characteristic of an interior landmark.” This had been another sticking point for preservationists, who emphasized that the clock tower had been open for tours in recent years and housed a renowned art gallery for four decades before the developers bought the building.

“There’s so much effort to appropriate public space in the city,” said Lynn Ellsworth, founder and chair of the Tribeca Trust. “We’re delighted about the ruling. I think that it clarifies important powers of the landmarks commission over public access.”

The preservationists who fought the electrical conversion also think it is unlikely that the city will appeal the decision, since such a move would put it in an awkward position.

“If the city were to appeal, it would be resigned to arguing against its own jurisdiction and asserting that it lacks the power to protect the interior landmarks entrusted to its care,” said Michael Hiller, the attorney who represented the plaintiffs in the suit, which also included the Historic Districts Council and Save America’s Clocks.

Neither LPC nor the city’s Law Department responded to requests for comment.

Hiller said the certificate of appropriateness was only annulled with respects to claims that were made in the lawsuit, which means the conversion project can still move ahead — although no work can be done that would close off the clock tower and prevent it from being serviced in the future.

The project will create 144 condominiums in the tower and a restaurant in the two-story former banking hall of the building, as well as some sort of community space.

Community Board 1 just last month also renewed its call for the clock to be preserved in its manual state — as well as for a long-lost globe sculpture to be recreated at the top of the clock tower — when the project’s architects presented the board’s Landmarks Committee with a proposal to amend their original plans by installing an elevator and relocating a grand staircase into the restaurant. Both CB1 and LPC approved those changes.

As for Schneider, he said his services were still on offer — and he hopes the developer would put the lawsuit behind them and focus on what’s right for the treasured timepiece.

“He may be a little miffed that he lost the case. But I feel that a thing like that should be put aside, and that we should work for the common good,” he said. “I bear no ill will, and I hope that he doesn’t either.”

The developers did not respond to requests for comment, and it is unclear whether they plan to appeal the decision.