BY SARAH FERGUSON | Immigration and border politics were unexpected themes at this year’s Acker Awards ceremony — an annual event to honor the pioneer rebels of the Downtown arts scene.

While most of the nation was home watching the Grammys, a packed crowd gathered at Lorcan Otway’s Theatre 80 St. Mark’s Sunday night to pay tribute to some of our local countercultural heros — the artists, poets and musicians who’ve made “outstanding contributions in their discipline in defiance of convention, or else served their fellow writers and artists in outstanding ways.”

The Acker Awards were created in 2013 by documentarian Clayton Patterson and writer Alan Kaufman, who hosts a parallel awards ceremony in San Francisco. The name comes from novelist Kathy Acker, who lived both in San Francisco and the East Village, and whose work exemplifies the kind of risk-taking that defines a true “avant-garde artist,” according to Patterson.

This year’s New York City event was co-sponsored by The Villager and Overthrow, the boxing gym that took over the former Yippie headquarters at 9 Bleecker St.

All told about 50 people received awards, so the audience was mostly past and present honorees and their friends. That gives the Ackers a real community feel — something like a high school reunion crossed with an East Village “greatest hits” variety hour.

Octogenarian scenester and writer Anthony Haden-Guest opened the night by honoring “Countess” Alex Zapak, a British performer and “c— rocker” who used to hold court at the now-defunct Pink Pony on Ludlow St. Some have called her the inspiration for Lady Gaga.

But Zapak couldn’t come collect her award in person because she has been barred from entering the U.S. since 2010, when customs officials cited her for overstaying a Canadian visa by 16 days.

Zapak was supposed to be banned from the U.S. for five years, but it’s two years beyond that and she still can’t get in, caught up in America’s border-police state.

So Haden-Guest accepted her award — a pizza box full of CDs, poems, art and other ephemera donated by the 49 other Acker recipients — in her absence.

At least Istvan Kantor was able to make it to the show. Last December, Kantor, who now lives in Toronto, was turned back at the Canadian border by U.S. customs officials, after they discovered a graffitied megaphone and hypodermic needles in his luggage. These were props for the “Neoist conspiracy” performance he planned to stage at the East Village release party for the long-awaited compendium he edited called “Rivington School: ’80s New York Underground.”

But the U.S. border agents weren’t into his irony; Kantor said they detained him for three hours and grilled him on whether he’d visited any Muslim countries lately.

Admittedly, Kantor, a.k.a. Monty Cantsin, has something of a track record, having been arrested numerous times for splattering his blood on the walls of museums — the last was 2014 at the Whitney, when he got busted for defacing a Jeff Koons retrospective. This time Kantor left his needles behind and said he had no border issues.

“It was amazing,” he told the audience. “Even the airline captain greeted me and said, ‘Thank you for your art.’”

Nevertheless, the fact that two white, non-Muslim artists could face such obstacles — even before Trump’s border clampdown — is troubling.

“How can we stop this constantly growing, infectious, control-freaking authority?” Kantor demanded. Aside from that, there was little politics on display, and scant mention of Trump — save for the comments of Lincoln Anderson, The Villager editor in chief, who when receiving his award for “Community Media” recalled the time he interviewed Trump in 2010 at the real estate mogul’s ribbon-cutting for his new Trump Soho condo-hotel.

“He was the weirdest guy I ever met. He gave me the weirdest interview,” Anderson said, drawing laughter from the crowd. He noted that his item in the Ackers box was a column he wrote about that encounter.

Speaking right before Anderson, was another Acker honoree, Eden Brower of Eden and John’s East River String Band. Brower ended her acceptance speech with, “I can’t help saying this whenever I have a mic in front of me — F— Trump!”

The other “Community Media” award went to Lucky Lawler of the rock and punk zine NY Waste.

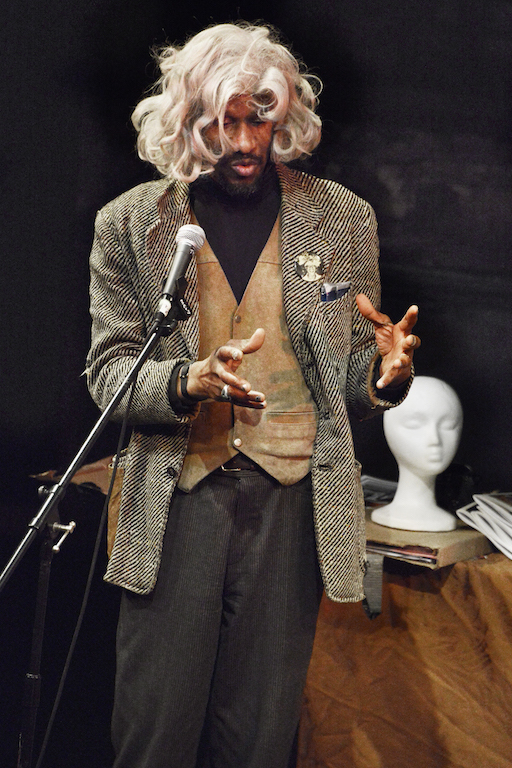

It being the Ackers, some of the award categories were quite eclectic. Sur Rodney Sur, who helped launch the East Village art scene with fellow gallerist Gracie Mansion — and who also helped

found the Green Oasis community garden — was awarded the Candy Darling Activism Award, for his role in archiving the works of artists who died of AIDS and assisting with their estates.

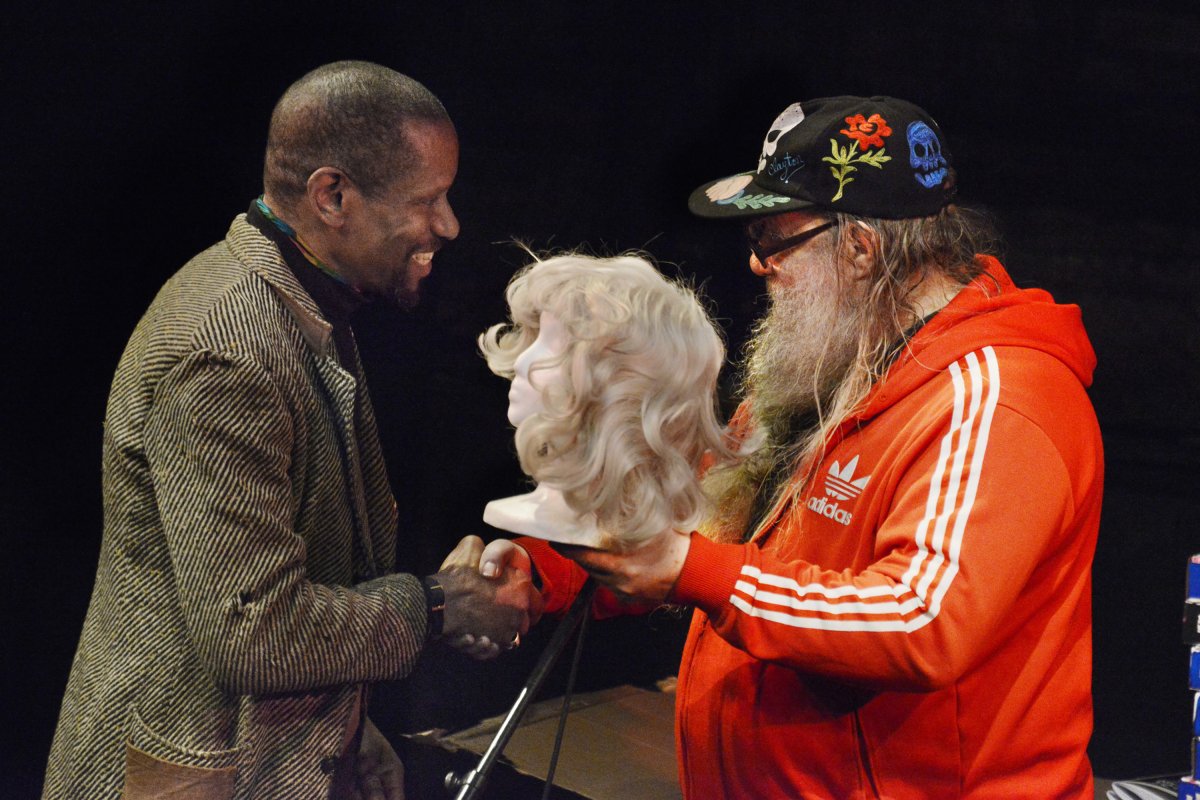

Appropriately, Sur accepted his box while donning a platinum wig that Darling — one of Warhol’s superstars — once sported.

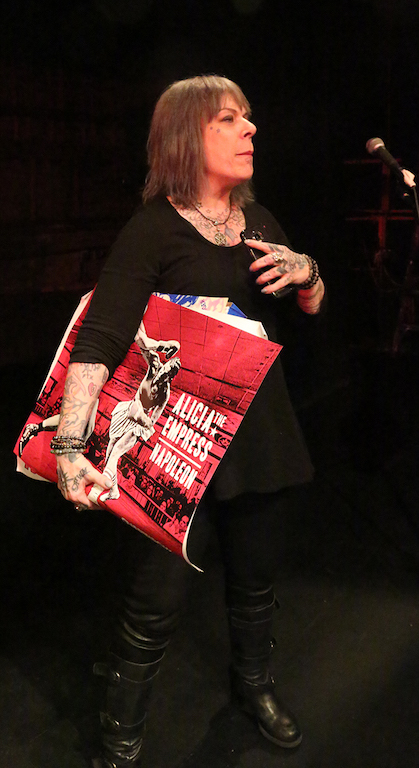

Former sex journalist and performance artist Veronica Vera got the award for “Sexual Evolutionary” — for establishing the world’s first cross-dressing academy, Miss Vera’s Finishing School for Boys Who Want to Be Girls.

And boxing coach Carlito Castillo — whose grit and knowledge apparently inspired the creation of Overthrow Boxing — got the “Art and Science of Boxing” award.

Many of those honored have roots in the counterculture of the 1960s. Actor Marilyn Roberts was one of the original La MaMa troupe members. Magie Dominic helped preside over Caffe Cino, considered the birthplace of Off Off Broadway.

Photographer and WOW Cafe co-founder Jackie Rudin recalled being drawn to the Lower East Side in 1967, after hearing Bob Fass on WBAI.

“I feel very proud. This was my world,” she told the audience.

Others were relative newcomers, like Anne Hanavan, a former sex worker turned lead singer of the band Transgendered Jesus.

“It’s just so incredible that the years on the streets selling my ass have turned into something good,” Hanavan told the audience. “So it’s proof of art as healing.”

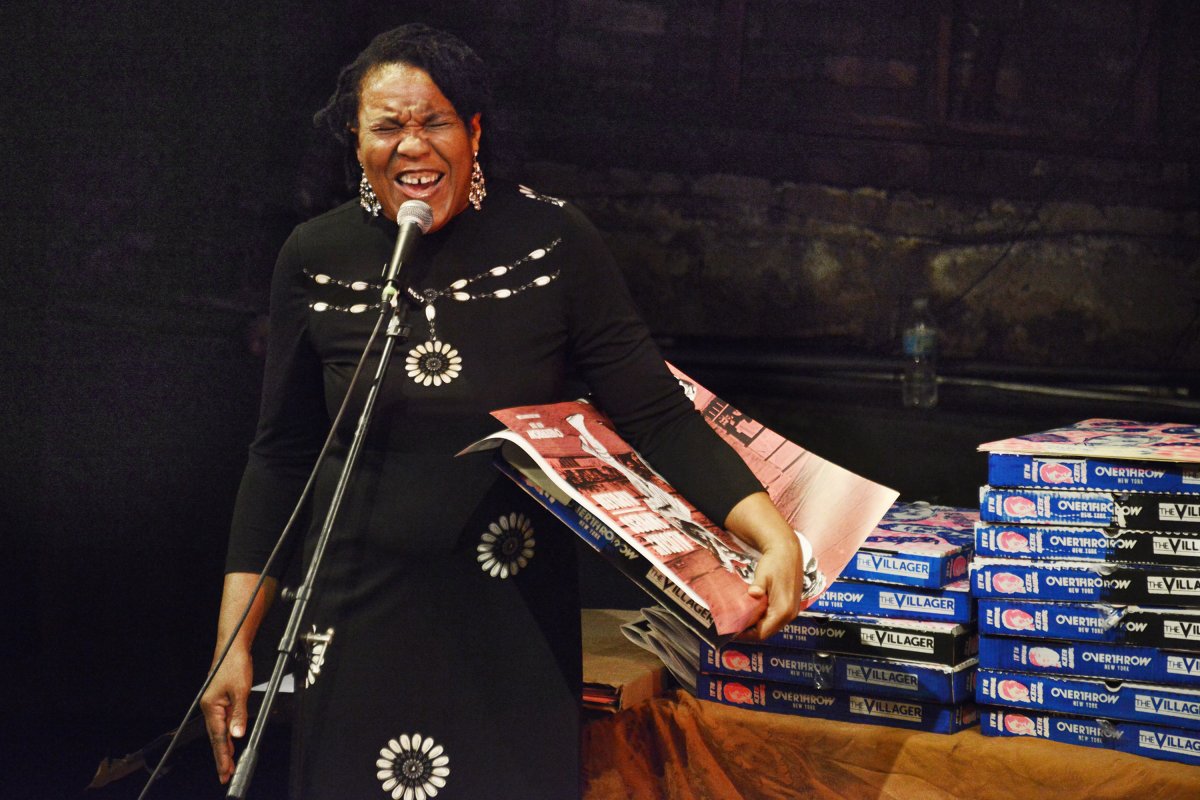

Given the range of talent in the house, it’s surprising that the Ackers don’t feature much actual performance. We only got a brief tastes, like when soul rocker Felice Rosser of the band Faith took the stage and belted out a lick worthy of Nina Simone.

But it’s the community that comes through, the way everyone’s art and existence seemed to bounce off and inform one another. Rosser recalled working the night shift in the early ’80s at a dive on Second Ave. with fellow Acker recipients Charles Schick and Regina Bartkoff. She remembered how graffiti artist Michael Stewart used to come through after the Pyramid Club let out.

These subtle and not-so-subtle intersections are what the Ackers are about.

“The one ambition I’ve had is to try to save as much of the community as possible,” Patterson told the crowd. He sees the Ackers as one way to do that. Recipients don’t get a plaque, but instead a box of artifacts contributed by other recipients.

Although the artists themselves often complain about having to supply 40 or more copies of their work to supply the D.I.Y. boxes, Patterson defended the concept.

“Over time, you get these collections of stuff and these booklets,” he said, holding up the program. “It’s like building up an encyclopedia of bios — tracing out a family tree.

“You start making all these links between all the people, and so it describes the old community. It’s like building this community abstractly, which we were all part of,” Patterson said.

The “booklet” Paterson referred to is the annual Ackers “chapbook,” which contains photos and bios of all the honorees, and — as usual — was designed by Michael Shirey, The Villager’s art director. Each box given to the honorees contains a booklet.

“I’ve been in the East Village since 1980,” remarked jazz flautist Cheryl Pyle, another Ackers ’17 winner. “I moved here with $100 to play jazz, and this means so much to me. The community is really all the arts, and when we combine we’re much stronger.”