By Sascha Brodsky

Owners of some historic buildings could be eligible to rake in a cash windfall. They can apply for a façade conservation easement, a program that trades a promise to preserve historic facades for tax benefits.

It sounds great but applying for the easement can be a bureaucratic nightmare. That’s where programs like the National Architectural Trust steps in. The Trust handles all the paperwork and sends its staff historians to evaluate the building.

The gain for the building owner? A tax break worth up 10-15 percent of the building’s value, claims the Trust.

Not so fast, says a local group, which wants a piece of the easement action itself. The group, called the Historic Neighborhood Trust, says that the National Architectural Trust is taking too large a slice of the pie, usually 10%. The neighborhood group is offering to do the work on a sliding scale of 8% for the first million, and 5% on benefits above $1 million. The group also says that it will use the money earned from the easement to benefit the local community.

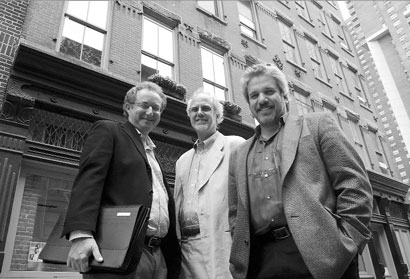

The Historic Neighborhood Trust was formed after 9/11 by three men who wanted to help revitalize Lower Manhattan.

“We thought that there is a lot of damage here but a lot of spirit so we should put together an organization that takes on various projects like putting in park benches and improving garbage pickup,” said Mark Winkelman, an architect and Tribeca resident and one of the founding directors of the group. Winkelman says that the group plans to plow back 10-25% of their fee into community projects.

Winkelman said that he first heard about the easements the trust was offering when he was approached about his own condo at 64 N. Moore St.

“When I got through the whole process I discovered that they were requesting a donation that would have been an awful lot of money,” he said. “That’s when I thought that we should investigate what this organization is doing with the money and started wondering whether we shouldn’t be trying to keep the money in the community.”

“We are seeking to take resources that come from this program and plow them back into the community,” said Jon Chodosh, another founder of the Historic Neighborhood Trust. “We have many ideas and we are going to have some fun figuring out what to do here. We don’t see other groups using the easement program to do anything community based.”

The Historic Neighborhood Trust only recently received its non-profit status and has not yet done any easements although the group said that it has several “in the pipeline.”

Winkelman said that the National Architectural Trust is running an “aggressive” marketing campaign, using fliers and ads to publicize their services. One difference between the two groups is the price. The National Architectural Trust based in Washington, D.C., asks for a “donation” of about ten percent of the easement or about $10,000 on a million dollar property.

But the National Architectural Trust says it also takes on local projects. It recently worked to bring back cobblestones to some Lower Manhattan streets. The Trust also sets up conservation programs in schools.

“The federal government makes you jump through hoops,” said Steven McClain, a member of the board of directors of the National Architectural Trust. “We take that responsibility off the property owner at no loss to you. The National Park Service has to approve the process but we have an architectural historian who will help shepherd it through.”

Paul Sisson, an owner of 345 Greenwich St., said that the 10 percent he paid the National Architectural Trust to handle his easement was well worth it.

“It’s an organizational nightmare dealing with this yourself,” he said. “They were very solid and very professional.”

Many building owners like Sisson find that dealing with the bureaucracy of the easement can be intimidating. The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentive Program lets owners of historic properties donate a facade conservation easement to a non-profit group and therefore claim a tax deduction for the charitable contribution. The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentive Program has been in place since 1976. It was established to ensure that the integrity of the historic property’s exterior is maintained.

Only a tiny percentage of buildings are eligible, however. To be eligible, the property must be located either in a historic district listed in the National Register of Historic Places or identified as a landmark property on the Register.

The easement is a legal agreement between the property owner and the non-profit group to protect a historic building’s facade. The owner promises not to change the outside appearance of the property without the non-profit’s permission.

According to the National Architectural Trust, the organization which holds the easement inspects the property annually and is obligated to assure that the property is in compliance with the terms of the easement. Any easement should be written by a lawyer and clearly stated.

The income tax deduction for the easement runs 10-15 percent of the fair market value of the property, according to the National Architectural Trust. As a benchmark, according to Dean Johnson of the National Architectural Trust, for every $1 million in fair market value of a building or condo unit, owners will receive on average a $110,000 personal income tax deduction and donate $11,000 to the Trust, which is also tax deductible, making the total tax deduction $121,000. The I.R.S. treats the donation of a facade conservation easement as any other non-cash charitable contribution. When deducting the appreciated value of the property, an individual may claim in one year an amount up to 30 percent of his or her adjusted gross income. They can carry forward up to six years.

One possible downside to the easement is that the legal agreement can make it more difficult and expensive for owners to maintain the property or sell it, experts said.

Meredith Kane, a real estate lawyer at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison L.L.P. and a member of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, said once the easement is donated, any work done to the facade of the building will have to be approved not just by the Landmarks Commission but also by the not-for-profit holding the easement, applying the standards of the federal Secretary of the Interior, which differ in some respects from the L.P.C. standards.

“Thus, the regulatory maze does not end with the donation of the easement, but will subject property owners to increased scrutiny on any future facade work [such as changing windows,]” Kane said.

Roger Schmidt, who obtained an easement for his Tribeca building last year through the National Architectural Trust, said that the possible drawbacks did not dissuade him. The easement he obtained was worth about $150,000, he said.

“For that kind of money I don’t worry about tiny problems down the road,” he added. “More people should be taking advantage of this program. For historic property owners it’s a no-brainer.”

McClain said that while his group does not have a set fee it asks the property owner for a contribution that is usually about ten percent of the easement.

“We don’t have any government funding and it’s a big process,” he said.

The National Architectural Trust has an $8 million endowment and manages easements on about 350 properties in New York City.

When Winkelman of the Historic Neighborhood Trust was asked if he can guarantee that his new organization will fund local projects with a portion of the fee, he said: “We are living in the community and will be answerable to the community. The mobs will be at our front doors if we do the wrong thing.”

Dean Johnson, local area manager of the National Architectural Trust said of the Historic Neighborhood Trust, “They are a new trust, are inexperienced, and have not recorded one easement to date. They do not have an established endowment. This work requires expertise and financial stability and they have a long way to go.”

WWW Downtown Express

Read More: https://www.amny.com/news/dance-31/