BY ZACH WILLIAMS | New money invested by city government into the New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) will result in better service, more transparency and increased cooperation with other city agencies, according to DOB Commissioner Rick Chandler.

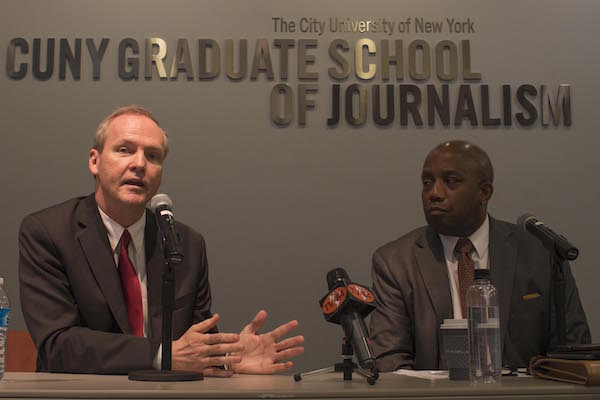

About $121 million in new investment over the next four years will fund 320 new inspectors and other staff to a department increasingly reliant upon technology in order to accomplish its mission of overseeing building safety throughout the city. Data analysis can help identify buildings (and landlords) not in compliance, while more online resources can streamline the construction of affordable housing and make more department data publicly accessible, Chandler said at a Sept. 18 forum held at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism (219 W. 40th St. btw. Seventh & Eighth Aves.).

“We’re going to use data like we’ve never used it before,” Chandler said.

An online system capable of handling 100 percent of permit applications as well as payments can boost transparency and provide the hard information necessary to power the digital effort. The department also intends to make more of these records publicly accessible, he said. Scrutiny comes with the job, added Chandler, who was appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio in July 2014. He did not offer a specific date or program for increasing public accessibility to DOB records.

“[The DOB is] a place where people take pride in what they do, and we all know that we’re under the watchful eye of others as the government should be. So we all kind of take that as a point to stand up and say: ‘Be proud of the fact that people are watching what you do, and make a decision that you think is right,’” Chandler said of the culture among the 1,300-person DOB staff.

A crane accident last spring left several people with minor injuries when a heating and air-conditioning unit weighing several tons fell from a building crane on Madison Ave. While unfortunate, the incident reflected the efficacy of a proactive approach on the part of the DOB towards building cranes, Chandler said. Building inspectors were on-scene for the heavy lifting, he added. DOB inspectors evaluated the work plans and the crane was operating early in the morning with the roadway temporarily closed — minimizing the danger, he said.

Data analysis can bring attention to contractors with poor safety records, or reveal fake details submitted by architects, engineers and developers, he said. Recent gas explosions have led to thousands of inspections as well as regular meeting among employees from the DOB, Con Ed and National Grid, said Chandler.

Addressing corruption within the agency also requires effort. Seven months ago, 11 DOB employees were indicted (along with 39 other city employees and private individuals) for faking inspections, dismissing building violations and other alleged graft, according to the Associated Press.

Chandler said that the investigation into the alleged graft came from his own agency. The department cannot compete on equal terms with the monetary temptations of the private sector, he noted.

“It’s frustrating to see that some people make the wrong decision but at the same time it’s also reassuring to know that the referrals about these concerns emanate from our own staff — so that’s a part of the culture,” he said.

The department now tracks inspectors via GPS to create “a bread crumb trail” of inspectors’ whereabouts, Chandler said. Yet technology can only go so far in addressing many of the safety and quality of life issues facing the department.

Buildings owners often deploy “sidewalk sheds” in order to shield pedestrians from falling debris breaking off of aging façades. The department requires that owners submit reports concerning the health of all sides of a building (not just those facing the street) every five years for buildings more than six stories or 75 feet, Chandler said. But many building owners simply erect the sidewalk sheds for reasons beyond safety per se, necessitating an evaluation of DOB regulations that is ongoing, he added.

“Clearly some owners feel that it pays to just pay the cost of the sidewalk shed rather than pay for façade repairs,” he said.

Chandler added that abuse of After Hours Variances — which allow construction late at night, early in the morning and during the weekend — rely upon public complaints. Local residents have said in the past that calls to 311 have done little good because inspectors did not mobilize in time to catch violations, Chelsea Now reported in the July 17, 2014 article “Making Some Noise About After-Hours Construction.”

He expressed confidence that the DOB adequately enforces limits on construction noise made outside of regular working hours. The department issued 44,000 After Hours Variances in 2014, Chelsea Now reported in the April 23, 2015 article “CB4 in Top After-Hours Construction Tier.”

Chandler said the necessity of the variances was on full display as he made his way to the school through the hectic traffic of the West Side.

“If you make a justification, then generally we are going to provide that permit…just driving up here today I can see how a lot of the work should probably have been much better executed if it would have been done overnight or over the weekends. We find that so much of the work which is done after hours is done for a very good reason,” he said.