BY JONATHAN SLAFF | On Sept. 7 there was an afternoon memorial for Edward R. Enderlin, the garrulous man known as “The Mayor of Perry Street.”

A compact and warm collection of his friends, supporters and social service workers gathered at The Lee, supportive housing at 133 Pitt St., to share stories and savor the mysteries surrounding this gaunt, red-bearded, ponytailed raconteur.

He had lived roughly since the 1990s at and around the corner of Perry and W. Fourth Sts., guarding the neighborhood, panhandling and delighting everybody with his storytelling, which was mostly autobiographical. In recent years, he suffered with heart and pulmonary conditions.

He died June 17, five days shy of his 63rd birthday, in his room at The Lee, where he had resided for five years.

“Eddie” was a familiar sight if you lived in the neighborhood of Perry and W. Fourth, or if you frequented past or present businesses there, including Sam’s Deli, Sant Ambroeus, A.P.C. or Avalon Hair Salon (which formerly occupied the storefront that’s now Hotoveli, a fashionable clothier).

It’s likely that he knew you, too, since he seemed to know everybody by name. If you had time for him to chat you up, as he did in recent years while perched on a motorized wheelchair, you would hear about his friendships with local celebrities and business moguls (all true), his modeling career (mostly true) and his Vietnam War stories (hard to verify). Then he would relieve you of a few bucks for medicine, food or single-room-occupancy housing (before he lived in The Lee).

If you were like me, you had a feeling you were his donor of last resort. Probably at least 75 of us felt the same way. Eddie had a way of making you feel special.

That Eddie survived on the streets so long was a miracle, as was the support he received for so long from the ever-changing community of the West Village, which now seems to be losing its heart as it gentrifies. Eddie was a crank, but he was our crank. And I am sure that our charity toward him was partly a product of our self-definition as an accepting community.

He appeared in the community about 26 years ago and supported himself first by odd jobs — short-lived ones — then by reselling salvaged electronics, home furnishings and books that were discarded by the neighborhood’s wealthier residents. I remember buying three cordless phones from him at different times. And a bike lock.

Ali Eshtelle, who works evenings at Sam’s Deli — and therefore saw Ed every day — remembers buying three inkjet printers from him. As the neighborhood gentrified and the secondhand appliance trade waned, Eddie took to panhandling.

In fair and not-so-fair weather, he slept outside on the doorsteps. In blizzards and miserably cold nights, he often resorted to an S.R.O. room at the White House Inn on Bowery. But his favored resting place was the entryway of the storefront at 271 W. Fourth St.

A succession of nearby business owners tolerated him and offered various kinds of support. He maintained a self-appointed “neighborhood watch.” He also kept the block clean and tattled to neighborhood parents on the late-night adventures of their kids. (“Matt and his friends were skateboarding too close to Seventh Ave. last night.”) And he defended his turf against incursions by other homeless people.

The principal speaker at Ed’s memorial was his biographer-in-progress, Paul Critchlow, a former resident of Perry St. — now relocated to W. 12th St. — who was a Vietnam vet and found affinity with Ed, veteran-to-veteran. Critchlow was drafted in 1968 and served in Vietnam in the artillery and infantry as a forward observer during the bloody battle of Hiep Duc Valley. He was wounded by an RPG round and ultimately sent home with scars all over to show for it.

Eddie, for his part, falsified his age in order to enlist in the Marines. This part of his life story is true. He told everybody who would listen that he had been imprisoned and crucified by the Viet Cong, and he showed you scars on the front and back of both hands to convince you. That part of his service record is difficult to corroborate.

Critchlow initially met Eddie outside Sam’s Deli and was won over by the homeless man’s intelligence, honesty and engaging stories. Formerly a politics writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer, a spokesperson for a Pennsylvania governor (Richard Thornburgh) and a communications executive for Merrill Lynch & Co., Critchlow knew a good story when he saw one. So he offered to write a book with Eddie on their respective lives. They formed a pact. The book, unfinished at this time, has attracted interest from a prospective literary agent and a prestigious media columnist.

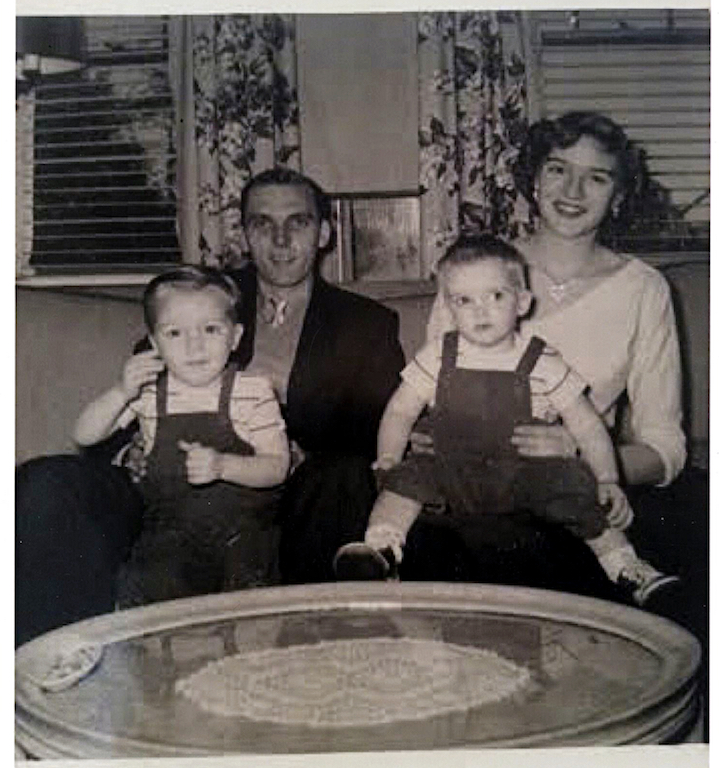

With his journalistic background, Critchlow knew how to fact-check and he sleuthed out Eddie’s estranged family and most of his personal history. He even located Eddie’s birth certificate and advocated for him to the Department of Veteran’s Affairs. At the Memorial, Critchlow related, “I found the mother of his children, his two children and siblings and spoke to some of them. Sadly, he was estranged from them. The main theme — which he freely admitted — was that Ed didn’t like to be fenced in by anything. He disliked responsibility, hated authority and couldn’t tolerate being told where to be, and when.”

Since Eddie had no permanent residence, his benefits checks and government correspondence had to be mailed to him care of Paul Critchlow’s Perry St. address. As Eddie fell into declining health and street life became less viable, Critchlow helped him connect with social-service organizations that provided casework and housing for the homeless, including Breaking Ground (formerly Common Ground) and Center for Urban Community Services (CUCS).

Ed was deemed eligible for housing assistance and initially moved into an S.R.O. complex in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, which he hated because it was far from the West Village. Subsequently, he lived at The Lee, near E. Houston St. and Avenue C, which was more conveniently commutable by bus.

Critchlow reflected, “Most of the time, he was extremely likable. No one could tell a story with the detail and animation that he could. Each chapter of his life, as he told it, was filled with amazing experiences — from growing up in an abusive household, to dropping out of school, to roaming around the South, getting involved with low-level mafia figures, spending time in juvenile prison for a failed robbery attempt with a toy gun, lying about his age to sign up for the Marines, fighting abroad, marrying, divorcing, having children, getting rich during the oil boom in Texas, going bankrupt, becoming a male model, and so on.”

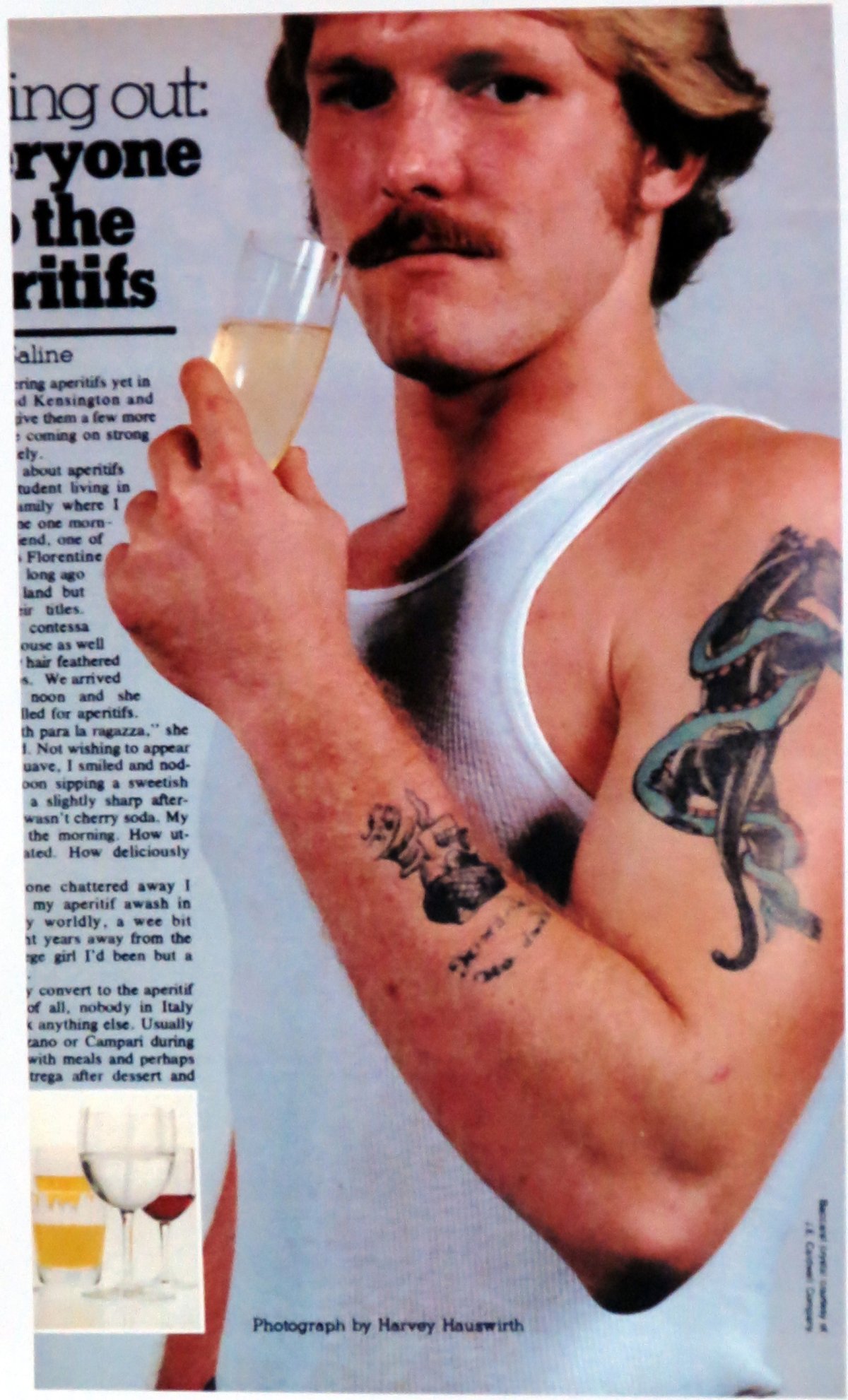

One of the most memorable images on display at Eddie’s memorial was a snazzy photo of him — handsome, young, muscular and tattooed — illustrating an article about aperitifs that ran in Philadelphia magazine in the late ’70’s. His older, gnome-like visage appears in Humans of New York, the photoblog and book that features street portraits and interviews collected on the streets of New York City.

N.Y.U. filmmakers often interviewed him or cast him in their projects, and a well-known photographer included Eddie’s portrait in “Old Masters,” a series for the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Critchlow and his wife, the novelist Patricia McCormick — whose books include socially conscious young-adult novels and a 2013 biography of Pakistani female-education activist Malala Yousafzai — frequently gave modest amounts of money to Ed. This was fine until the day Ed panhandled one of their young sons. Patricia came to the corner, crooked her finger at him and icily admonished him never to ask her kids for money.

After that, Ed did a terrific imitation of her warning and said he feared Patricia more than anyone else on the block. One frigid November night, “Patty” sent Paul out to find Ed and make sure he had money for a hotel. Ed later said no one had ever done anything like that for him before and he was truly touched to learn it was Patty’s idea.

Unlike other panhandlers, whose times in the neighborhood became short, Ed had the good sense to never solicit patrons of the Sant Ambroeus sidewalk cafe. He knew how to stay in everybody’s good graces. His approach was more personal. He had standing appointments once a month with major donors, including heiresses and hedge-fund employees, who gave him hundreds of dollars. Low-wage workers, like neighborhood hairdressers, were known to hand him $25 per week.

Ed was a difficult person, irascible at times, with outbursts that reflected the anger of the unfortunate. Staff members of who attended the memorial related how Ed would vent his temper on them, then later call them to apologize. Ed was quirky, willful and unique, but he was not nuts. It was clear to everyone who knew him in the West Village that he was not a victim of alcohol or drugs, but that he had formidable demons in his own personality. He lived honestly — by a strict code of conduct, even if it was his own. He viewed himself as a contributing member of the neighborhood, and in many ways he was.

Officers of the Sixth Precinct accommodated him, partly because he was harmless, partly because respected residents of the neighborhood vouched for him, and partly because he served as the cops’ “eyes and ears” when shady people entered the neighborhood.

Nevertheless, living rough took its toll: frostbitten toes in winters, a broken hip in a bike-truck collision, fights and various illnesses. On freezing nights, neighborhood members would often spring for a cab to get Ed home. Frequently, Ali Eshtelle drove him home at midnight after Sam’s Deli closed. Ed promised to reciprocate when the movie rights to his book came in: He’d drive Ali around in his limo.

He was picked up by an ambulance from Sam’s Deli twice in the past year. Last February, suffering heart fibrillations, Ed checked himself into Lenox Hill Hospital, where he made sure Paul Critchlow knew what to do with his share of the book proceeds.

“I want half of it to go equally to each of my kids,” he said. “And I want the rest to go to veterans in need.”

Edward R. Enderlin was born in Cuero, Texas, the eldest of five children, but raised on the Jersey Shore. His father died when Ed was 14, and this is when he began spinning off the rails. His mother, now deceased, was psychologically and physically abusive, as he told many people.

Ed didn’t finish high school. Estranged from his family, he lived a few years with his paternal grandparents. He couldn’t stay focused in school and always had issues with authority.

He lived in Long Island and New Jersey, married, divorced and fathered two children. He landed in our neighborhood by chance from Miami, where he said bad people were after him after a failed drug deal. He helped some guys move furniture to New York and they left him off in Tompkins Square. From there he wandered into the West Village.

He took a room on Perry St., which he was able to finance for about six months by doing odd jobs, like painting and hauling. Although he eventually lost the room, he had taken to the quiet streets and tolerant people of the neighborhood and made it his permanent home.

Most residents sensed his love for the area, although some were dismissive. He seemed good-natured and there was consistency in his stories. He was well-read, quoting Shakespeare and various philosophers, and knowledgeable about many movies and pop culture, which he attributed to lots of TV watching. And he was a great mimic.

Many of Ed’s friends and supporters remain in the neighborhood, but some predeceased him and others have moved Uptown. At the memorial, a sprinkling of them shared personal remembrances with varying degrees of openness. Present were an equal number of social-service workers who had known and worked with him.

Reverend Callie Janoff, who presided at the memorial — and who had not met Ed — closed the gathering with a blessing drawn from an old Irish toast that was especially apropos:

May you have food and raiment,

A soft pillow for your head,

May you be forty years in heaven

Before the devil knows you’re dead.

Jonathan Slaff has lived at Perry and W. Fourth Sts. since 1974. He is an actor, theater publicist and public member of the Community Board 2 Arts and Institution Committee.