BY TRAV S.D travsd.wordpress.com | Though all but forgotten by contemporary audiences, there was no bigger star than Eddie Cantor in his heyday. He conquered more media than even Bob Hope, Will Rogers or Jack Benny: vaudeville, Broadway revues and book musicals, films, radio, TV and — because he was much a singer as he was a comedian — record albums. He was the first openly Jewish male entertainer to mainstream (his characters were always Jewish or “Russian” — a euphemism). The first entertainer of either gender to do it was Fanny Brice.

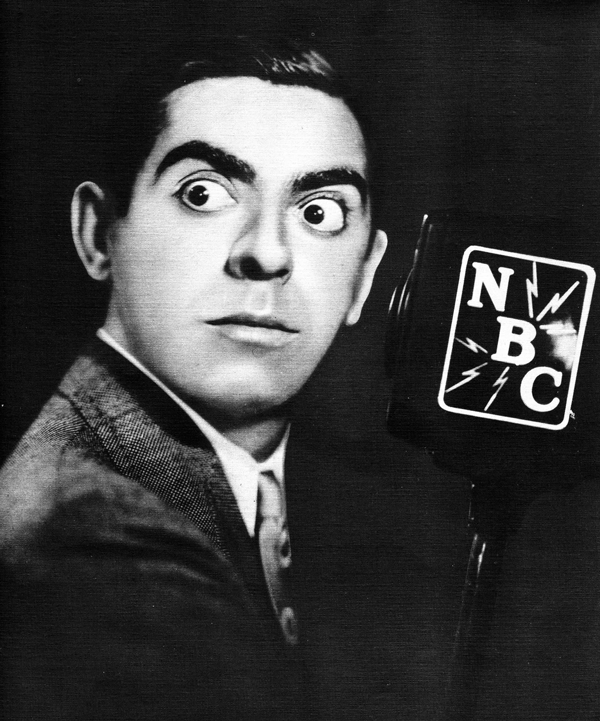

Cantor was definitely a creature of his times — very strange by today’s standards. Known as “Banjo Eyes” on account of his huge, rolling orbs, he was equally a singer and a comedian. He sang and recorded several crazy, nonsensical songs that were the very soul of the 1920s, such as “If You Knew Susie,” “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” “Ma! He’s Making Eyes at Me” and the title song from his Broadway show and film “Whoopee!” (which Sinatra later covered). On the word whoopee, Cantor would roll his eyes and grin Groucho-style…although who’s to say Groucho didn’t roll his eyes Cantor-style?

Doctor: On what side are you

Jewish?

Cantor: On the East Side.

(From the sketch “Insurance”)

He was born Israel Iskowitz, the son of Jewish Belarussian immigrants, on Jan. 31, 1892. Orphaned at age two and raised by his grandmother in New York’s Lower East Side, Cantor endured poor circumstances. He wore rags, had little to eat and lived in a shabby basement. When his grandmother enrolled him at school as Israel Kantrowitz (her last name), the school thoughtfully took the liberty of shortening it to Kanter. At age 13, he changed his first name to Eddie to impress a girl.

Like nearly all children in the Lower East Side at that time, Cantor stole and hung out with street gangs. He was funny from early childhood, making people around him laugh on the streets (as Richard Pryor would later do) to keep tougher guys from terrorizing him. He was bitten early by the show business bug, although he could seldom afford to see an actual show. Cantor once stole a girl’s life savings of $12 so he could see a production of “Billy the Kid.”

Teaming up with his friend Dan Lipsky, he did comedy and sang, performing weddings and bar mitzvahs at Henry Hall, which was next door to his house. He left home briefly at 15 in order to shack up with a 19-year-old consort, but he was forced to go home with his tail between his legs after stealing the woman’s tickets to “45 Minutes to Broadway,” starring Fay Templeton.

In 1908, Cantor took the plunge into professionalism by performing at Miner’s Bowery Theatre amateur night. He was so poor he had to borrow a friend’s pants in order to go on. Despite a rough crowd, Cantor won the amateur contest and took home $12 ($10 prize money, $2 in thrown coins). Later that year, he got a job in a touring burlesque show with producer Frank B. Carr called “Indian Maidens” but was stranded with the show in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania (an old story in vaudeville).

In 1909, he became a singer at Carrie Walsh’s Saloon, Coney Island. The pianist was 16-year-old Jimmy Durante. They made a sort of loose team, learning every popular song from the past 20 years in order to fulfill audience requests. When they didn’t know a song, they would make one up around the title, and if the requester seemed displeased, say “What, there are two songs by that name?”

Cantor diligently saved his money from this work and invested in a new suit and business cards, so he could make the rounds with agents. Worn down by Cantor’s persistence, small time agent Joe Wood finally sent him out to Gain’s Manhattan Theatre just to be rid of him. The theatre was famous for sending acts packing. Shockingly, Cantor did so well he ended up being retained by the theatre. The impressed Wood started sending him to upstate theatres.

Cantor was working for the third-rate People’s Vaudeville Company when its owner Joe Schenck (later to become a movie mogul) told him if he came with some new material, he would be held over. Cantor solved the problem by doing the same act for several weeks in different ethnic personae: Hebrew, German, Blackface. The Blackface was a real revelation, as Cantor’s large round eyes read really well through the makeup.

Cantor made the big time in 1911 when he was hired by the juggling team of Bedini and Arthur to join them at Hammerstein’s Victoria. At first, Cantor was little more than a glorified assistant, never on stage, just fetching things for Bedini. After he passed this test for a few weeks, he was given a walk-on part in the show. His job was simply to walk across the stage and hand a plate to Bedini. Yet somehow Cantor managed to get a laugh even at this, walking on with an “attitude.” Bedini, the boss of the act, gradually expanded his part with spoken lines, bits of business and even juggling. Essentially Cantor and Arthur were Bedini’s stooges, black-face servants who supported the master juggler who was the star of the act.

As usual, Cantor gave 110 percent and gradually upstaged Bedini. During this period, Cantor developed a character that would have revolutionized blackface, had blackface survived. His character deviated from all stereotypes. He was a sort of sissified, bookish character who wore glasses (Groucho Marx called the character “a nance”) and would say mincing things like “He means to do me bodily harm!” By defying stereotype, this was a step in the direction of realism — but of course, total realism came thereafter when black parts became exclusively played by real blacks.

Largely through Cantor’s efforts, Bedini and Arthur (Cantor remained unbilled) gradually moved up the bill to better and better spots. After seven months with the team, Cantor got a chance to sing with the act in Louisville when the manager needed them to pad for time. He sang Irving Berlin’s “Ragtime Violin” and scored a huge hit — not just for his singing ability, but for his hyperactive onstage movements, which included handclaps and a sort of crazy-legged dance. Cantor would move this way on stage throughout his singing career.

In 1912, he got an offer to perform with the Kid Cabaret. He purposely got himself fired from Bedini’s act so he could take it. Also in the cast of the Kid Cabaret was a young George Jessel, with whom Cantor became lifetime friends. In the act, Cantor played Jefferson, a blackface butler. They worked the Orpheum Circuit in 1913, where Cantor first met Will Rogers, another lifelong friend. Rogers took to Cantor and mentored him, even recommending him to his agent, the powerful Max Hart, who began to represent him.

Upon turning 21, he left Edwards. He performed as a single for a few months, visiting London in 1914 to play “Charlot’s Revue” while on his honeymoon. The trip was cut short by the outbreak of World War I, however. Back in New York, he teamed up with Al Lee, Ed Wynn’s former straight-man, in an act called “Master and Man.” Lee sang ballads, which Cantor interrupted with nutty remarks.

The act stayed together until 1916, when Cantor was hired by Earl Carrol to play the part of the chauffeur in a show called “Canary Cottage.” In rehearsals, Cantor upstaged the star Trixie Friganza, who threatened to walk if he was allowed to keep it up. Silent comedy star Raymond Griffith, who happened to be in attendance, advised Cantor to lay off until performance and then pull all his stunts. Which he did, to great appreciation from the audience. With such laughs, the producers were forced to back Cantor.

The next step was Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolics, his rooftop after-hours follow up to the Follies. Cantor was given a one-night trial, and his appearance was a triumph. He constantly did crazy, spontaneous things (like asking the likes of William Randolph Hearst to hold their hands high over their heads for a magic trick and then ignoring them for twenty minutes while they suffered). He gave an entirely different performance each night, a necessity at the Frolics, for the audience was the same each night, mostly composed of New York’s “400 ” (high society’s old money millionaires).

Cantor was a very New York sort of character, impudent and familiar. His style in delivering a song was kinetic and eye-catching. He even had a signature exit — a little hankie he waved at the audience. In 1917, he was moved up to the Follies where he got to perform with Bert Williams, Fanny Brice, W.C. Fields and Will Rogers. In these early days, Cantor, in his eagerness to please, overdid everything, overplaying, mugging, etc. His newfound friends in the cast counseled to cool it down a little, and he went over even better.

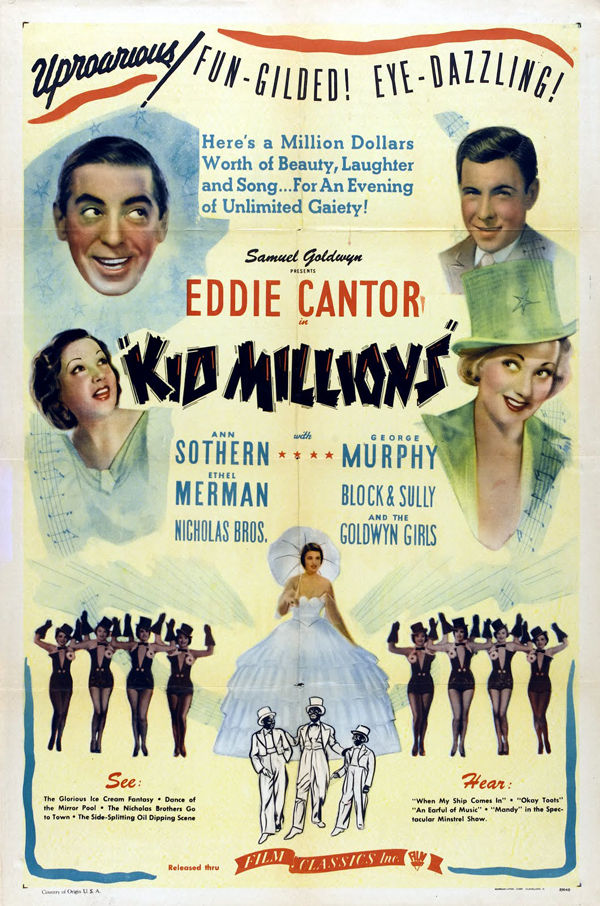

Cantor went on to star in numerous musicals, such as “Make it Snappy” (1922), “Kid Boots” (1923) and “Whoopee!” (1928). His first film “Kid Boots” (1926) was a silent version of his earlier musical. His second silent, “Special Delivery” (1927), was a flop. With and without blackface, he was one of the biggest stars of early talkies. Films like “Whoopee!,” “Palmy Days,” “The Kid from Spain,” “Kid Millions,” etc. were big hits and remain as peculiar artifacts of a bygone era. The films are very much akin to the early Marx Bros. pictures — extremely unpredictable, almost surreal, semi-musicals.

Cantor became one of radio’s first big stars. Starting with “The Chase and Sanborne Hour,” he dominated the form from 1931-54. He was also big on TV from 1950-55, primarily for his show “The Colgate Comedy Hour,” which was successful for its first two years — but then a heart attack robbed Cantor of all of his strength and vitality and greatly reduced the energy of his performance.

The television Cantor was very different from the one of the films. Heavier, huskier, he was no longer the skinny “nance” of the 20s and 30s, but a grandfather whose appeal lay primarily in nostalgia. His last recording date was in 1957. Much of his final years were given to causes. Cantor founded the March of Dimes, for example. He had been a founding member of Actor’s Equity, AFTRA and the Screen Actors Guild, and was a big supporter of Israel upon its founding.

Eddie Cantor passed away in 1964, far, far away from the Lower East Side basement he’d shared with his grandmother.

Trav S.D. has been producing the American Vaudeville Theatre since 1995, and periodically trots it out in new incarnations. Stay in the loop at travsd.wordpress.com, and also catch up with him at Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, et al. His books include “No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous” and “Chain of Fools: Silent Comedy and its Legacies from Nickelodeons to YouTube.”