BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | After a pressure-packed process that saw Community Board 2 and the Hudson River Park Trust clash over the fate of Pier 40 — and a leading C.B. 2 member resign from the board in protest — the state Legislature recently finally voted to allow commercial office use on the gigantic W. Houston St. pier.

Some speculate this could allow Google to sail in as the anchor tenant for yet another Hudson River Park pier. The tech behemoth — which eventually plans to occupy a vertically expanded St. John’s Building across the West Side Highway from Pier 40 — already is slated to be the main tenant at Pier 57.

As the state lawmakers did six years ago, when they quietly approved air-rights transfers from the park, they again voted on these latest legislative amendments for Pier 40 in the final hours of their session two weeks ago.

The amended legislation was sponsored by Assemblymember Deborah Glick and state Senator Brian Kavanagh, whose districts contain the pier. Governor Andrew Cuomo still needs to sign the bill.

A draft version of the amendments was first publicly unveiled in late May.

In a major change since then, the approved modifications now say that any Pier 40 development plan must go through the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, or ULURP.

However, the Hudson River Park Trust, the state/city authority that is building and operates the park, still wants the governor to make further modifications — to lessen restrictions on building size on Pier 40 — which could happen when the Legislature reconvenes in January.

State Senator Brad Hoylman, whose district abuts Pier 40, said it was a challenge to navigate between the demands of C.B. 2 (the Village) and C.B. 4 (Chelsea/Hell’s Kitchen), which have been feuding over how much revenue Pier 40 should be contributing to the park’s overall operating budget.

“To be candid, there are a lot of people below 14th St. who think this is too much,” Hoylman said of allowing an office building to be developed on Pier 40. “And there are a lot of people above 14th St. who say this is not enough. It’s a very difficult balance — to have a steady stream of revenue for the park, plus not having an office park on the Hudson. C.B. 4 feels C.B. 2 hasn’t been pulling its fair share — which I disagree with.”

In a first-of-its-kind process, working over the last six months, local politicians took it upon themselves to hash out the legislative amendments to the Hudson River Park Act of 1998 — the park’s founding legislation — saying they based their ideas on the previous recommendations of the C.B. 2 Pier 40 Working Group.

The politicians’ first publicly released their draft legislative proposal right before the Memorial Day weekend, then held a public forum the following Tuesday. In addition to concern over the eyebrow-raising timing of the release and forum, there was no shortage of criticism, particularly from C.B. 2 members. Foremost, they protested, was that the modifications didn’t mandate that Pier 40 development plans go through ULURP. But the recently passed legislative changes address that very clearly.

“Development or redevelopment [of Pier 40] shall be subject to and shall comply with the provisions of New York City’s uniform land use procedure,” the amended Park Act now reads.

For its part, the Trust says the Park Act already had language requiring this and that it was always assumed any project would go through ULURP.

In another addition to what the local lawmakers put forth before Memorial Day, the amended legislation requires the Trust to form a Pier 40 Task Force composed of local community members and local city, state and federal politicians “whose districts abut the park.” The task force is to include six to eight members of C.B. 2, plus one member each from C.B. 4 and C.B. 1. The task force will weigh in on any future request for proposals, or R.F.P., that the Trust would issue for developers pitching projects for the pier. However, the task force will not be involved in selecting the winner of the R.F.P. process.

Following the legislative changes, the Park Act now allows up to 700,000 square feet of “business, professional or governmental office space” on Pier 40. In addition, the Trust, the state/city authority that is building and operating the 4.5-mile-long park, is now allowed to have up to 50,000 square feet of office space and 50,000 square feet of operations space on the pier. (In fact, though, the Trust already has office and operations space on the pier.)

Maximum height for buildings and structures on Pier 40 also has now been capped, under the amended legislation, at 88 feet – although 20 additional feet is allowed for mechanical systems, such as housing for the top of elevator shafts. It was C.B. 2 that, in its advisory capacity, previously recommended a height limit of 88 feet — the top of the pier’s tallest gantries.

The park’s founding legislation established Pier 40 as the largest “commercial node” for generating revenue for the park. Yet, unlike car parking, which is an allowable use at Pier 40, for example, commercial office use was not. Commercial office use was originally not allowed in the park at all, but an amendment in 2013 allowed it at Pier 57 in Chelsea, where Google will be the anchor tenant.

During the most recent process, local youth sports leagues — like Greenwich Village Little League and Downtown United Soccer Club — had called for specific language mandating playing fields on Pier 40, and also wanted to keep the fields at ground level.

“Any development or redevelopment,” the modified legislation says of Pier 40, “shall provide for playing fields [of] not less than three hundred and twenty thousand square feet, provided that every effort is made to place as much playing field space at ground level as is feasible.”

The original Park Act required that a minimum of 50 percent of the pier’s footprint be preserved for passive and active public open space. Under the newly modified legislation, however, that number would increase by 15 percent if the pier were to be significantly redeveloped — for example, such as with a taller building.

As the updated Park Act now states, “[I]n such event that the Pier 40 building is developed or redeveloped with new or substantially rehabilitated structures for business, professional or governmental office use, then the equivalent of sixty-five percent of the footprint of Pier 40 shall be passive and active public open space.”

The youth leagues, however, had hoped for even more field space — up to an additional 140,000 square feet, between outdoor and indoor space. There also has been shifting opinion on whether it would be best to keep the existing pier-shed “donut” on the pier as a wind buffer for the playing fields. Park activists say the Trust has indicated it wants to raze the old pier shed and construct a new office building on the pier’s northern side, but the Trust now denies this.

As for who gets to use the fields — another concern of the leagues and C.B. 2 — the new language added to the Park Act states, “[A]ny passive and active open space that may be developed or redeveloped…shall be available to the general public without professional or commercial activity.”

The amendment further states, “Any proposal for development or redevelopment shall give equal preference to adaptive reuse of the existing structure.” This was another advisory stipulation by the Village/Lower West Side’s Board 2: namely, that any future redevelopment of the pier try to preserve as much as possible of the existing pier-shed structure.

Furthermore, the amended law now allows the Trust to offer a longer, 49-year lease for Pier 40, with the option of a 25-year renewal, followed by another renewal of up to 24 years — which basically could total two years short of a 100-year lease.

Any development now must also provide space for a boathouse for small-scale boating on the pier’s south side, no smaller than currently exists. Boating activists had advocated fiercely to keep their space on the pier.

Hoylman praised the group effort of the local politicians, including himself, who honed the legislative amendments.

“This is like an unprecedented alliance,” he said of the pols’ unified front.

That said, Hoylman criticized the park’s basic economic structure, saying it’s what causes these constant dilemmas over issues like development in the park.

“If people are unhappy with it,” he said of the latest Pier 40 changes, “it’s because it’s based on a flawed model. It’s a private development model, and it’s bad. I would like the park to become a city or state park.”

He then promptly blasted Republicans former Governor George Pataki and former Mayor Rudy Giuliani for creating the situation, charging, “That’s what the previous generation of Republican leadership bestowed us.”

In a statement, the Trust said, “The importance of Pier 40 for the park’s overall financial health and as a recreational resource cannot be overstated.

“The legislation that just passed does not solve the collective problem because it will require public funds to create all of the public space.

“Over the coming months, we will see if we can develop a workable plan for Pier 40’s redevelopment using the tools that are available to us. We appreciate all the hard work our elected officials and their staffs have put into this process.”

In saying the legislation “does not solve the collective problem,” the Trust’s statement appears to imply that the size restrictions on commercial office development at Pier 40 would prevent the pier from generating enough revenue.

Similarly, Connie Fishman, executive director of Hudson River Park Friends, the park’s main advocacy group and private fundraiser, in a statement, referred to “burdensome restrictions.”

“Legislation was passed to amend the Hudson River Park Act to allow Pier 40’s rehabilitation,” she said. “While the legislation passed is not perfect, and has some burdensome restrictions, we are hopeful the governor will amend the legislation to ensure the park can earn sufficient income from the pier. We thank Assemblymember Deborah Glick, and state Senators Brian Kavanagh and Brad Hoylman for moving forward on saving Pier 40.”

Glick and Kavanagh did not immediately respond to requests for comment for this article. And, indeed, there was “radio silence” from local politicians until after the legislative changes were approved.

Similar to Hoylman, Susanna Aaron, a C.B. 2 member who is on the Friends’ board of directors, said she would like to see the park get more government funding and “a solution that will render a financially sustainable park.”

“I don’t like the opposition, the idea that it’s somehow the Trust getting everything the Trust wants, as if the Trust were something other than the park,” she said. “All of us who love the park just want to see it be safe and beautiful and finished and healthy for a very long time.”

Tobi Bergman, a former C.B. 2 chairperson and longtime waterfront park advocate, resigned from the community board just days after the local politicians unveiled their draft legislative changes in May. Bergman said the elected officials had ignored the board’s asks for Pier 40 — notably the ULURP requirement, which is now part of the legislation.

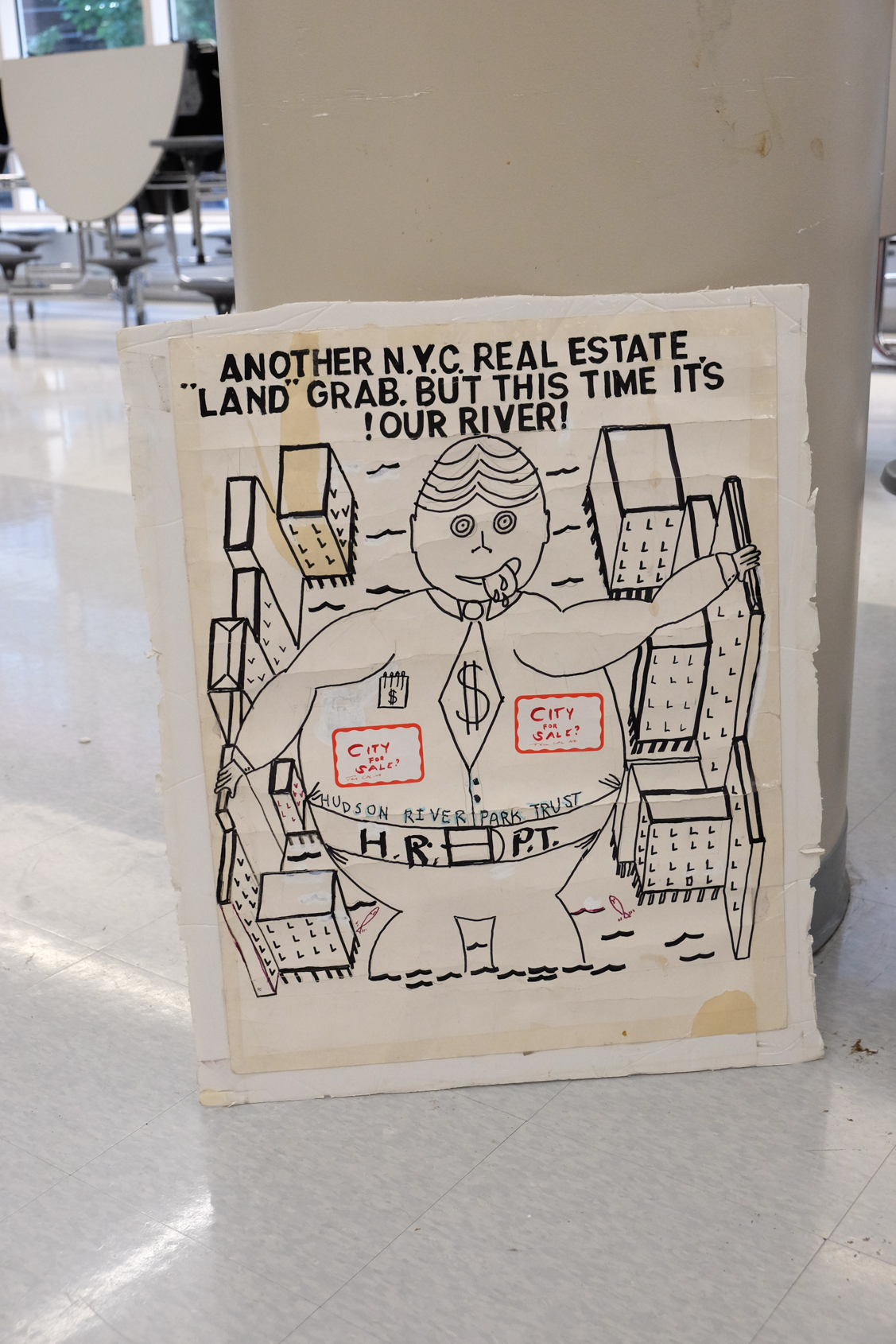

Asked his take on the Pier 40 legislative changes, Bergman said, “Three big office buildings [at Piers 40, 57 and 76] will greatly diminish the public value of the waterfront park. Selling off parts of a successful park that enabled the redevelopment of the West Side of Manhattan will diminish the stature and pride of our city.”

(Pier 76 doesn’t currently allow commercial office use — but, the way things are going, Bergman predicts the Park Act will be changed to allow it.)

“And when the children return to the pier after years of demolition and construction,” Bergman said, “the wondrous protected courtyard of the brilliantly repurposed old maritime pier will be replaced by ordinary fields exposed to the glare and harsh winds of the waterfront. That’s why the elected officials who pushed hard to get this done are not lining up to take credit.”