BY STEPHANIE BUHMANN

Museums offer ‘a full spectrum of excellent exhibitions.’

With the holidays upon us, New York galleries are taking a brief break. While most commercial art venues will be closed for a two-week period surrounding New Year’s Eve, the city’s museums remain open — offering a full spectrum of excellent exhibitions.

Through January 2, The Morgan Library & Museum (www.themorgan.org. 225 Madison Ave., St.) will present Roy Lichtenstein’s black and white drawings from the 1960s. While Lichtenstein’s paintings (inspired by commercial illustrations and comic strips rendered in highly saturated hues) are most prominent, his preparatory drawings, sketches and collages remain little-known. Curated by Isabel Dervaux, this exhibition makes the latter group its sole focus and succeeds in tracing Lichtenstein’s exploration of drawing as an expressive medium. Most of the 55 works on view were created during the early and mid-1960s.

By then, Lichtenstein was in his late thirties and had already exhibited regularly for a decade. He was a mid-career artist working within the context of Abstract Expressionism and Cubism, still searching for a unique voice to describe his own time. After encountering the works of Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg (who incorporated everyday objects and cited popular culture in their works), Lichtenstein began to look in a similar direction — and soon developed an interest in advertisement campaigns and comic books. The compositions on display reveal the concentrated editorial process as well as his focus on line. Contextualized with clippings from newspapers, magazines and telephone books, the black and white works reveal the extent of Lichtenstein’s self-imposed challenge to create what critic Lawrence Alloway once described as “an original artwork pretending to be a copy.”

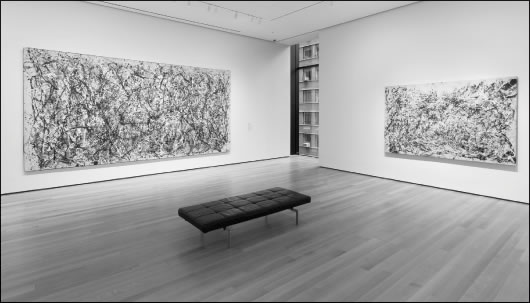

The one art movement that carries this city’s name is Abstract Expressionism — also known as The New York School. The institution that supported it early, and subsequently helped to make many of its members famous, is the Museum of Modern Art (11 W. 53rd St. btw. Fifth & Sixth Aves.). It seems appropriate that at the end of the first decade of the new millennium, MoMA (www.moma.org) pays homage to its heritage, hosting “Abstract Expressionist New York.” On view through April 25, the exhibit draws exclusively from its own collection. Spanning various floors and involving the drawing, print and film departments, the exhibition’s most significant display can be found on the fourth floor. Subtitled “The Big Picture,” the installation is comprised of 100 paintings and about 60 sculptures, drawings and prints. Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman are represented here with multiple works. In addition, artists who have almost vanished into obscurity (such as Hedda Sterne) or who have only recently been rediscovered (such as Norman Lewis) are represented with one work each.

As it does not include outside loans from other institutions, this survey provides valuable insight into MoMA’s collecting politics — revealing whose work the curators judged to be of greatest importance at the time and aimed to acquire in depth. Of course there are omissions (one of the more obvious being the talented Giorgio Cavallon).

The best aspect of this exhibition is that it provides a chance to study MoMA-owned works usually buried deep in storage, including several works by Richard Pousette-Dart, early work by Pollock, canvases by Lee Krasner, immense sculptures by David Smith, monumental compositions by Franz Kline, or an odd little drip painting by Hans Hofmann.

Organized by the independent curator Amy Wolf, “On Becoming an Artist: Isamu Noguchi and his Contemporaries, 1922-1960” provides valuable insight into the complexity of the acclaimed sculptor’s oeuvre (The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum; www.noguchi.org; 9-01 33rd Road at Vernon Boulevard, Long Island City).

On view through April 24, the exhibition (which happens to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the museum) investigates Noguchi’s most potent artistic relationships. These are as multi-faceted as Noguchi’s oeuvre — which besides sculptures also entails garden, furniture, set and lighting designs, ceramics and architectural projects. In 1937, he designed a Bakelite intercom for the Zenith Radio Corporation, for example — and his glass-topped table, produced by Herman Miller in 1947, is still being produced today. Among the illustrious group of artists, performers, choreographers, composers, designers and architects who shaped Noguchi’s world, the most famous names include Arshile Gorky, Alexander Calder, Berenice Abbott, Frida Kahlo and Merce Cunningham. Noguchi’s creative dialogue with others occasionally resulted in collaborations, including an unrealized project with the architect Louis Kahn.

The exhibition sheds light on Noguchi’s formative years in 1920s Paris. That’s when, and where, Noguchi worked for the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi — who had a profound impact on him. Inspired by Brancusi’s reductive forms that exuded both a sense of purity and sensuality, Noguchi began to embrace a form of abstract modernism that allowed for emotional expressiveness and mystery. Informed by extensive travels throughout Europe, Asia and Latin America, Noguchi in later years applied this vocabulary to a wide range of materials. This show makes a point of featuring works made of stainless steel, marble, balsawood, bronze and ceramic.

For those interested in Native art from North, Central and South America, “Infinity of Nations” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian offers the perfect opportunity (www.nmai.si.edu. At the George Gustav Heye Center, One Bowling Green). “Infinity” is a permanent exhibition which debuted this past October after much anticipation. It consists of no less than 700 works — all organized by geographic regions.

Five years in the making, the show opens with a rather dramatic display of strength by featuring a rare macaw-and-heron-feather ceremonial headdress. Other objects include an Apsáalooke (Crow) robe illustrated with warriors’ exploits; a detailed Mayan limestone bas-relief depicting a ball player; and an elaborately beaded Inuit tuilli (a woman’s inner parka) made for the mother of a newborn baby. The show manifests as a discourse in the vibrancy of Native American culture — and is further proof of how diverse New York’s cultural resources truly are.