BY HARRY PINCUS | I wish my father was here, to see the Mets play in the World Series.

He was a Brooklyn Dodger fan who took me to Ebbets Field, and gave me the gift of a team to follow. Baseball is about generations, players who hold our attention for a season, and fathers who hand the game over to us forever. Teams that are a birthright, and a religion.

The Mets are the direct descendants of the Brooklyn Dodgers…“Dem Bums”…and their loyal fans. Dodger fans were the schlumps who worked in the factories, the post office and the sewers. We rightfully claimed more spirit than the pinstriped rich kids who rooted for the Yankees, though far less success. On the rare occasions when we won, the world seemed to stop and take notice.

The Yankees march to the field beneath a quote from General Douglas MacArthur, “There’s No Substitute For Victory.” The Mets have a whole circus of substitutes for victory. If the Yankees are somehow militaristic and organized, the only religion attached to the Mets must be the irregular lurch of anarchy, and a required belief in miracles. Ya gotta believe! In this special year, we’ve won something significant.

It still moves me to think of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Jackie Robinson, who broke the racist system, a few blocks from where I grew up.

I met Robinson once, when he was a soul caged within the Corporate Beast, working for Nelson Rockefeller. He was a Republican by then, and so sad. Had he lived as a free man, he could have joined his Rachel when his number 42 was placed in the Jackie Robinson rotunda of the new Mets ballpark. He could have had a hot dog at Nathan’s in Coney Island, and strolled over to the bronze sculpture commemorating the moment Pee Wee Reese put his arm on the second baseman’s shoulder, and welcomed him to the team.

Like everyone, my father, Irving, was devastated by the loss of the Dodgers in 1957. What could he, a poor subway conductor, a Coney Island handball player, do but bring his 5-year-old son to one of the last games?

So it is that I remember standing outside of Ebbets Field, beneath the big awning, as my father bought two tickets “for a buck” from a kid on a bicycle who said he was ready to give them away. Sure enough, the seats were two rows behind the Dodger dugout, and the best seats Irving had ever had. The legendary ballpark didn’t look like the old grainy newsreels; it was full of color and sound. Guys in white walked around the stands with enormous coffee urns on their backs… “Your mother should have one of those,” my father joked. And then, there they were, emerging from dugout, right before my eyes…

THE BROOKLYN DODGERS!

When they built Shea Stadium, Irving took me there in the winter to watch the steel going up. There was a World’s Fair opening just across the street, and we believed in the future, then.

My father and I always sat behind home plate, high up in general admission. The $1.65 seats. Perhaps heaven is general admission, or perhaps Irving has an even better seat. We saw Jim Bunning pitch a perfect game on Father’s Day, and Lou Brock hit an insane home run into the center field bleachers at the Polo Grounds.

But nothing could surpass the miracle of game six in the ’86 World Series. The Mets were down to their last strike over and over again, until a little squibbler went through the wickets of Boston’s sorry first baseman. The evening had already been distinguished by a nut who parachuted onto the field in the middle of the game, but the miraculous ending, with the entire stadium shaking, was a thousand times better than Woodstock.

Of course, Irving, then in his 70s, had never been to a World Series game. There are so few of them for Mets fans; they’re like the most significant rings on an old tree. Markers of youth and middle age, drought and abundant rainfall. Anyway, World Series tickets are just for rich guys.

Well, in 1986, Irving’s “goilfriend” worked for a magnate in the toy industry, who gave her two tickets to game six. This was going to be a night for the ages. We decided to prime for the game with a fine dinner at Luna, in Little Italy.

As befit the evening, a large fellow in a tweed jacket with a horseshoe of platinum hair sat down next to me, and I realized that it was Divine, in his street clothes. I tried to alert my father to the celebrity dining amongst us, but he barely noticed. As we left the restaurant, he asked me what I was gesturing about.

“We were eating next to Divine,” I said. “Do you know who Divine is?”

Of course he didn’t: “Who’s Divine?”

“He’s an underground film star,” I explained.

“Underground where? What’s he famous for?”

I didn’t have time to explain. We were outside the restaurant now, and on our way to what turned out to be the greatest World Series game in the history of New York.

“He’s famous for eating dog s— in a movie, O.K.?” I answered, nervously.

At that moment, the large, glowing figure of Divine himself appeared in the doorway, just behind my father.

“WELL IF HE EATS DOG S—, WHAT’S HE GOTTA EAT HERE FOR?” shouted my father, over the din of traffic. “THIS IS TWENTY BUCKS!”

My father’s final season was more than 20 years ago, a rotten summer when the Mets stunk, and the players went out on strike. He’d just reached his 80th birthday, and I tried to boost his spirits by talking about the upcoming Ken Burns “Baseball” series.

By then, he was hospitalized, and in pain. I promised him that there was going to be an entire episode about baseball in New York, featuring the Dodgers. I held his hand, watching the glorious story of “The Capital of Baseball,” but I knew he was slipping away. The next day, Irving was gone. It was the last day of summer.

Years later, I brought my 7-year-old son to his first baseball game at Shea Stadium. P.S. 41 had latched on to some $2 tickets, and I thought it would be fitting, in the tradition of Irving, to bring his grandson to the general admission.

The seats were near the farthest corner of the very last row of the upper deck. I decided we should scooch over a few seats and sit in the absolute most-distant corner of the vast ballpark. Somehow, I had begun with the best seats at Ebbets Field, and here was my son beginning with the worst seats at Shea Stadium.

Isaac looked adorable in his Mets cap and long blond hair. We gamely climbed to the top of the nosebleed section, and arrived, huffing and puffing, to look out over the entire enormous stadium.

My little boy rose and threw out his arms.

“Dad,” he proclaimed, “THESE ARE GREAT SEATS!”

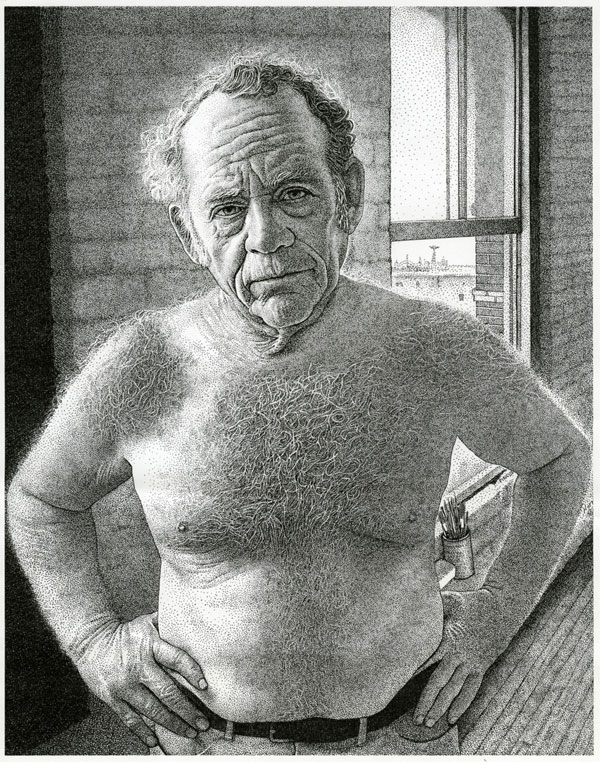

Pincus is an award-winning illustrator and fine artist. He lives in Soho.