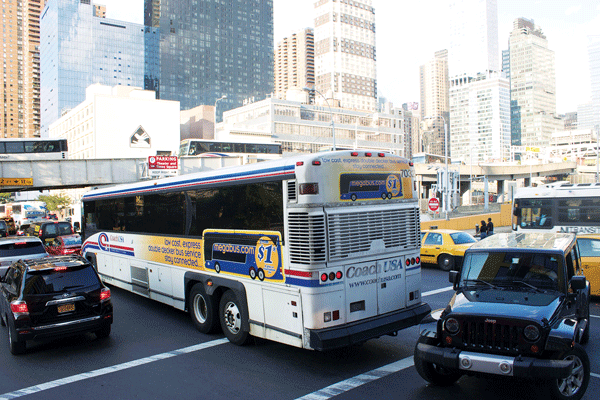

A jeep turns against traffic while a Coach USA bus blocks the intersection of 10th Ave. and W. 39th St.

BY ZACH WILLIAMS | Rush hour on 10th Ave. offers the unmistakable odor of exhaust, the ceaseless rumble of engines and the sheer volume of human movement between the under-sized Port Authority Bus Terminal and the western shore of the Hudson River.

A line of NJ Transit buses stretched from W. 36th to W. 40th Sts. on Aug. 6, along the eastern curb of 10th Ave. — idling far beyond the city’s three-minute limit. In the other lanes, competition grew as more and more buses from carriers such as Megabus, Peter Pan and Coach USA entered the four-lane avenue leading to W. 40th St. Some turn right there towards the bus terminal, while most of the remaining buses move one block further, where two lanes of traffic lead west into the Lincoln Tunnel.

Traffic sometimes gets so thick that vehicles progress mere feet per green light. Getting through an intersection requires deft movement, utter attention and improvisation for drivers and pedestrians alike. Whenever buses block intersections, people go outside the crosswalks and into the intersections — and private automobiles are not above doing the opposite. Nearby construction equipment stored on street in front of the Hudson Yards development does not help.

With 200,000 passengers and thousands of buses traveling through the aging bus terminal every day, the congestion was already a familiar topic for Community Board 4 (CB4), as well as the collection of government agencies and non-profit groups involved with local transportation issues. Lasting solutions will take years to implement, but action in the short-term could lessen the circumstances that have put pedestrians in harm’s way.

A July 14 collision on W. 47th St. and 10th Ave., during which two pedestrians (tourists) were struck and seriously injured by a Trans-Bridge Line, spurred the community board to once again seek action on the gridlock and associated safety issues. It remains to be seen whether the city Department of Transportation (DOT) will install signs on W. 44th and in the W. 40s between Ninth and 10th Aves. warning drivers of turning restrictions, as requested by CB4 in a July 28 letter — but DOT has consistently acted upon community suggestions in recent years, according to a March CB4 letter to Mayor Bill de Blasio.

“There has been a substantial increase in the number of commuter buses using the Lincoln Tunnel in the last several years,” states the July letter to DOT Borough Commissioner Margaret Forgione. “Many empty buses, typically entering from either the Lincoln Tunnel or parking spaces further south or west, enter the Port Authority between 4 p.m. and 6 p.m. each weekday to load passengers and then depart. Traffic regulations require empty buses to use ‘Through’ or ‘Local Truck Routes’ to arrive at the Port Authority.”

Permitted routes run from Eighth to 11th Aves., the entire length of W. 42nd St. and along W. 40th St. between the tunnel entrance and 11th Ave., states the letter, before adding: “Unfortunately, drivers of empty buses are illegally using other residential streets within Community District 4.”

DOT has yet to respond, according to CB4 Transportation Planning Committee Co-Chair Ernest Modarelli.

CALLS FOR A MORE VISIBLE POLICE PRESENCE

The NYPD needs to deploy more traffic and parking enforcement to the area between W. 30th and W. 47th Sts., argued CB4 in another July 28 letter, this one sent to NYC Police Commissioner Bill Bratton.

“We appreciate that there has been a slight increase in the number of traffic agents at intersections during rush hour since our request earlier this year,” reads the letter. “However, these new placements are only during rush hour, not during heavy bus inflow on 10th Ave. in the afternoon and at a couple of intersections. In addition, there remain very few infractions being issued to buses, despite the clear violations of both traffic and parking requirements.”

Modarelli said the police department’s response to the letter was similar to past efforts: they deployed a few more officers to 10th Ave., who are no longer seen after a week or two.

“It’s touch and go, it never lasts,” Modarelli reflected.

“It gets kind of insane,” said Ray Schaub, an occasional passenger of the M11 bus line, which moves uptown on 10th Ave. Interviewed on Aug. 6 near the 34th St. M11 stop, he noted that his quest to return to his Upper West Side residence with his young son in tow necessitated a special strategy that day: a car service.

Pedestrians, meanwhile, followed maze-like paths through the canyon of buses, big trucks and beleaguered private automobiles. As she waited for her opening to cross the street with her young son, Corletta Alleyne reiterated the same observation as policy makers.

“They don’t have anywhere to put [the buses],” she said.

Nearby, a police officer shook his head as he wrote a citation for one idling NJ Transit bus, but there were a dozen more up ahead. Technically, some of them only remained in one space for a green light or two, before advancing a bit further up the avenue. As one emerged from W. 37th St. to slip into 10th Ave., another blocked its way — needing a few feet of the intersection to accommodate its advancement along 10th Ave. The other driver would have to wait — at least 15 minutes.

“It’s rough,” said the NJ Transit driver of the rear vehicle who declined to give his name. “Everybody wants to go home.”

PLEAS AND PLANS

The afternoon of Aug. 6 featured the same rush hour madness described by the CB4 letters, but previous attempts to be heard amidst all the bureaucratic noise surrounding the issue have hardly been successful. The community dynamics of the problem have drastically changed in the years following the 2005 rezoning of the surrounding area, which brought in thousands of new residents to an area known previously for its industry.

A decade ago, the congestion did not impact residential life so much, but now something must be done, CB4 wrote to NJ Transit in January. The letter requested a meeting with the transit agency to discuss pedestrian safety, bus idling, a routinely blocked M11 stop at W. 37th St. and the idea of diverting some of the buses to 12th Ave. — which an MTA spokesperson said (in an email to Chelsea Now) would conflict with the upcoming M12 bus line, as well as block a current bus depot at W. 40th St.

This was not the first time that CB4 reached out to NJ Transit, according to a Jan. 9, 2014 letter, which followed a similar one sent on Oct. 6, 2010.

“The conditions have not changed and our community continues to struggle with safety and quality of life concerns caused by the improper operation of your buses. We feel the inaction is unusual and not appropriate for a major bus company,” reads the January 2014 letter which adds: “CB4 actively supports the Port Authority’s efforts to build a new bus garage on the far west side or in Secaucus, NJ, which would mitigate these problems. However, building the garage is likely several years away and these matters of safety cannot wait.”

A representative of NJ Transit said in an email to Chelsea Now that the agency did not have the letter on file, but would forward a copy provided by Chelsea Now to the relevant officials. The NYPD is responsible for enforcing traffic laws, the agency said.

“NJ Transit is working collaboratively with the city of New York, the NYPD and the Port Authority, which operates the terminal, to address the issues of congestion around the terminal,” the agency said in response to a question regarding current action on the problem. An MTA official stated a similar commitment to negotiation among CB4, DOT and other relevant parties.

A DOT study released in April (the Clinton/Hell’s Kitchen Neighborhood Traffic Study) issued several recommendations — including improved signage, turn prohibitions on troublesome side streets, altering 11th and Dyer Aves. to better absorb rush hour traffic and expanding Port Authority Bus Terminal in order to address the traffic congestion resulting from tunnel traffic. No mention of 10th Ave. was made in the summary of its findings. While the report concluded by stating that increased enforcement would be needed in order to properly implement its recommendations, the word “enforcement” appears only eleven more times in the 82-page document.

“The main traffic problem to be addressed is the chronic congestion caused by vehicular access to and from the Lincoln Tunnel,” the report notes.

PORT AUTHORITY UPGRADE IN THE WORKS

The Port Authority, for its part, is in the midst of preparing an 18-month master plan to determine the future of its bus terminal.

“The functionally obsolete facility no longer meets the transportation needs of the hundreds of thousands of riders that pass through the terminal every day, and the Port Authority is committed to identifying comprehensive improvements within the context of its existing Capital Plan. This initiative will make interim improvements to the terminal as the agency explores a program to deliver a redeveloped facility,” read a July 23 statement announcing $90 million in funding to update facilities within the terminal including dilapidated ceilings and bathrooms.

It is a good start, according to State Senator Brad Hoylman, who said in a July 24 statement that he looked “forward to working with the Port Authority as it continues to press forward with the Bus Terminal Master Plan, which would modernize and expand capacity of the depot and help keep idling buses off our city’s streets.”

Plans for a bus storage and staging facility (The Galvin Plaza Bus Annex, at W. 39th St., btw. 10th & 11th Aves.) are underway, with the Port Authority having submitted a request for $230 million from the Federal Transit Administration. An additional $170 million would be needed to realize the project according to projections. The Port Authority did not respond for a request for comment by press time.

CB4’s Modarelli said that without “major investment,” stricter enforcement is the only viable short-term option. In the coming years if political will and available funding coalesce, a canceled tunnel project could resume, allowing more traffic to simultaneously travel the Lincoln Tunnel. But what activists really wish for is a 7 train that would eventually traverse state boundaries, drastically reducing commuters’ reliance on automobile travel.

“That is the dream of all,” said Will Rogers, a member of local traffic safety advocacy group Chekpeds (the Clinton Hell’s Kitchen Coalition for Pedestrian Safety), of which Modarelli is a member.

In a recent email thread among the group, one activist christened the traffic situation in Hell’s Kitchen by a new portmanteau.

“Yes, it is ‘Busageddon,’ ” he wrote.