BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Supported by four columns, a square, granite canopy surmounts a fountain on the southwestern flank of Tompkins Square Park. “Faith,” “Hope,” “Charity” and “Temperance” are inscribed on the sides.

Temperance! The word sounds quaint now but when the fountain was erected in 1891, temperance, by then meaning total abstinence from alcohol, evoked as much passion as the abortion debate has in more recent times.

Temperance crusaders blamed drunkenness for poverty, crime, wife-beating and other social ills and wanted to make liquor illegal. Saloonkeepers and drinkers said that drinking was a private matter and should not be legally curtailed.

The Tompkins Square Park fountain is one of two temperance fountains in New York City. The other one is in Union Square Park and dates from 1881. They are relics of a movement that swept the country beginning in 1826 when the American Temperance Society was founded, followed by other organizations with similar goals.

The premise behind the fountains was that the availability of cool drinking water would make alcohol less tempting. In the 19th century, temperance fountains could be found in cities and towns from coast to coast. Now few of them remain.

As readers of the King James Bible may remember, the association of faith, hope and charity comes from 1 Corinthians 13: “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three: but the greatest of these is charity.” It’s not surprising that the Tompkins Square Park fountain references scripture. Protestant Christianity laced with anti-Catholicism was predominant in the temperance movement. And charity, of course, was considered a great virtue.

Both of the city’s temperance fountains were charitable gifts from wealthy men.

Daniel Willis James, who paid for the Union Square fountain, inherited his money. His grandfather was Anson Greene Phelps of Phelps, Dodge and Company. With the assistance of his cousin, William E. Dodge, Jr., James headed his grandfather’s company, turning it into one of the world’s largest mining companies.

Dodge, like his father before him, was the president of The National Temperance Society and persuaded his cousin to embrace the cause.

Henry D. Cogswell donated the Tompkins Square Park temperance fountain. He came from a poor Connecticut family, became a dentist and headed for California during the Gold Rush of 1848. There, he offered his dental services to miners, investing his earnings in real estate and mining stocks. He became one of San Francisco’s first millionaires.

Cogswell planned to erect 50 temperance fountains in various parts of the country. He started on this project in 1878 and managed to put up fountains in Boston, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, as well as Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and Rockville, Connecticut, among other locations. Some of the fountains were capped with statues of himself holding a cup in one hand and a temperance leaflet in the other. The Washington, D.C., fountain, which still exists, has intertwined fish spewing water with a crane on top of the canopy. Some of Cogswell’s other fountains were crowned with mythological maidens dispensing water from a jug.

The Tompkins Square Park fountain has a maiden — Hebe, the Greek goddess of youth and cupbearer to the gods and goddesses of Mount Olympus. She was modeled on an 1816 marble statue by the Danish sculptor Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen.

Cogswell’s temperance fountains were not popular. They were ridiculed, reviled and, in some cases, demolished by angry crowds. The Washington, D.C., fountain was considered so ugly that it led to the formation of fine arts commissions in other parts of the country to keep municipalities from having to deal with such gifts.

Cogswell had a hard time getting his Tompkins Square Park fountain accepted. He was rebuffed for six years. Finally, he allied himself with the Moderation Society, which had been founded in 1877 to address drunkenness on the Lower East Side. The Moderation Society managed to push Cogswell’s temperance fountain through the necessary city channels. On Aug. 27, 1891, the water was turned on.

Though Tompkins Square Park was bordered by a community of German-speaking immigrants who not only brewed a lot of beer but drank a lot of it, no one took a crowbar to Cogswell’s fountain, as befell his moralizing gifts elsewhere. But time took its toll. By the 1980s, the fountain was covered with graffiti. Someone had sawed off Hebe’s hands. Tompkins Square Park, far from being salubrious, was a haven for drug addicts.

In 1992, the statue of Hebe was replaced with a bronze replica and the fountain was cleaned. Now, it appears as a picturesque embellishment amid the park’s densely planted gardens and towering elms.

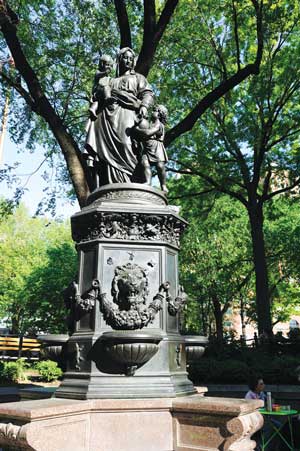

Daniel Willis James’s temperance fountain on the west side of Union Square Park is far more elaborate than the Cogswell creation. James used some of his ample fortune to hire a German sculptor named Karl Adolph Donndorf to design and build a tall, bronze fountain supported by a base of rosy granite imported from Sweden.

Above decorative swags, lion’s heads on the fountain’s four sides now once again emit water, after their recent repair. Bronze dragonflies and butterflies frolic above the lions. Then comes a richly sculpted band of acanthus leaves and birds. The ensemble is topped by a figure of a mother dressed like the Virgin Mary in a Renaissance painting. She holds a child in her right arm, while dispensing water from a jug to another child who looks at her adoringly.

Though the female figures atop New York City’s two surviving temperance fountains are idealized they are not misplaced. Saloons were for men only. Women and children suffered when the family breadwinner drank up his week’s wages and then came home angry and violent.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1874, drew its base of support from women who banded together to try to fight these abuses. Concurrently, some women were fighting for the right to vote. To some extent, the two movements merged. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who led the fight for women’s suffrage, also founded the New York State Women’s Temperance Society in 1852.

The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution establishing Prohibition in the United States became effective on Jan. 17, 1920. It was an outgrowth of the temperance movement. Also in 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution finally gave women the right to vote in federal elections. Prohibition was repealed in 1933 because the naysayers were right. It didn’t work. Women can vote, of course, but many don’t.

Manhattan’s two surviving temperance fountains are a testament to the heroic struggles and myopia of previous generations, always relevant but especially in this election year.