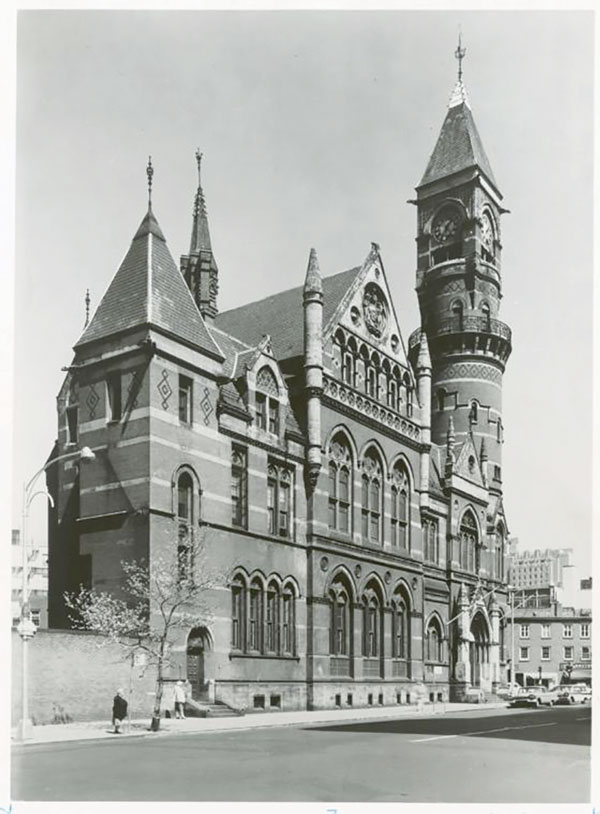

BY REBECCA FIORE | The Jefferson Market Library didn’t start off as a library. The High Victorian Gothic structure was originally built in 1874 as a courthouse. In 1945, it ceased being a courthouse and was slated to be demolished. Locals, led by community preservationist Margot Gayle, rallied together to save the building in 1959 and have it converted to a New York Public Library branch. Then in 1974, due to budget cutbacks, the N.Y.P.L. board of trustees voted to close the branch. One month later, after public outcry, the decision was rescinded.

“This library, in particular, was saved by the public twice,” said Mark John Smith, artist in residence and creator of JML50, a 50th anniversary celebration of the library. “We would not be standing here today had it not been for those people who grouped together to make sure the community had access to literature and learning.”

For a long while, branch library manager Frank Collerius knew he wanted an art piece in the Jefferson Market Library’s second-floor reading room, but couldn’t commit to an idea. Then he met Smith, and showed him a cabinet file drawer filled with old documents and letters from the public to the library. Smith lit up.

“Frank, how many more of those do you have?” Smith recalled telling him.

It turns out, tons.

“I felt like, ultimately, the only thing that would be appropriate and wonderful on the wall would be the public’s names and letters,” Collerius said. “The library wouldn’t exist without the public. I wanted to have the public’s words be as large as the windows and architecture in that room.

The first step was to dig through the archives. Collerius and Smith opened the documents to the public and let them decide what belonged on the walls. The library held two events during the summer, one for the public and one through the Young Lions, a special N.Y.P.L. membership group for people in their 20s and 30s who have a passion for literature and the library.

“We wanted to ensure the public were responsible for curating and selecting the content,” Smith said.

Smith, 30, said he’s obsessed with the idea of “materiality.” He said he feels it is valuable to be able to touch the archives and have a physical connection to them.

“I think it’s really important when creating a public work of art, especially, to have it be deep-rooted in the community it’s representing,” he said.

Donning white gloves, library staff and community members dug through the archives. Since some of these documents had not been on public view before, it was a new experience for both the public and library staff.

“The tremendously exciting thing was that we were seeing things as they were,” Smith said. “We were on that journey with them. The joy for us was discovering.”

What came together in the following months was a large-format, black-and-white, three-story 360-degree print on the walls of the reading room. Each vertical board-like strip has either a child’s signature — from the Children’s Registration Book — or quotes from letters and documents, or handwritten notes found in books by librarians.

“The amazing thing,” Smith said, “is when we started researching and looking through the archives, we noticed a lot of the patrons have gone on to be actors, artists, musicians or screenwriters because the Village is such a hub of creativity.”

For example, among them was actress Scarlett Johansson, who grew up in Greenwich Village and signed the Children’s Registration Book in 1992 when she was just 8 years old.

The vertical slats in the artwork are reminiscent to Smith of vintage flooring, with interlocking panels, and he sees them as literally being a structural element of the library.

“The voices of the community are holding this building up,” he said.

Smith also made a conscious decision to only include sentences that begin with “I,” so the viewers can, in a sense, put themselves in the original author’s shoes. Among the sentences in the artwork are “I’m out of work and I cannot afford to buy a book” and “I depend on the library for all my reading.” One letter written by a child simply said, “I lost another book.”

“I’d like to think that reading this is like reading a novel,” Smith said. “You just get lost in it.”

The slats are organized chronologically starting in 1967, with the library’s opening. Smith noticed small differences over the years in how people wrote and what they communicated with the library. Basically, the quality of penmanship has plummeted, only increasing with the advent of computers and smartphones.

“Handwriting has changed a lot in 50 years,” he noted. “You start off in the ’50s where everything is very cursive and within the lines, and as you move around toward the ’80s and ’90s, it all gets a bit more out there. It speaks as sort of a historical overview of how times have really changed. We wanted to celebrate the mark-making and smudges and bits of torn paper that really drive home the significance of analog communication.”

In fact, some of the signatures are just that, scribbles and smudges. Smith even included a water stain found in a registration book.

“I believe that a scribble is as important as any kind of language that you can write,” he said. “It’s communication at the end of the day and it has a certain type of urgency and joy to it that should be celebrated.”

Smith wanted to make sure that the art piece was never about him. A British artist who previously worked for the BBC, he has been a New Yorker for sometime now. He has been artist in residence for a year at the library where he has observed all that a library provides to a community.

“I honestly feel the library is the most reflective and adaptive public service there is,” he reflected. “Whatever kind of challenge or whatever request, it will respond in a way that is kind, generous and just giving. That happens on a daily basis and is largely unseen. They do not discriminate. You can stand here and watch people working. There’s people running their own company from the reading room desk.”

In addition to the handwriting on the wall, Smith incorporated a light element, which wraps around the room, illuminating parts of the archive. He said the lights change as the day grows into night. The lights remain out of people’s sight lines and avoid reflective surfaces. Smith said he wanted to make sure that, above all else, the reading room was able to keep its original purpose, without distractions.

He even commissioned a scent, which was casually filling the room at the artwork’s Nov. 16 opening night. The warm smell was a mix of leather, ink, wood and, of course, books. He said he wanted to make the reading room a bit more theatrical by adding different elements.

Also, on the library’s ground floor is another project Smith led — a display of posters made by library staff and locals in the style of the original protest protesters from the efforts to save the library.

To further the importance of the archival work, Matt Whitman has been filming each part of the process.

“This is such an important thing not only to document, but also something important to document on a medium that speaks to the time that the library was founded,” Whitman said. “Film, namely Super 8 film, would have been the only format to capture the process of this. It was one of the first really portable home movie formats.”

Whitman said he wanted to “capture the things that people don’t necessarily see when they see a work of art. They see it as a finished thing,” he said, “but they don’t see all the effort and the labor and the way it becomes part of the artist’s life.”

Smith said that, in another 50 years, at the library’s 100th anniversary celebration, people could look back at this current interpretation. He also said he wants to make sure that all that he has explored and created is available for anyone to see, just as the library is free to use. The art is also posted online via social media.

“I don’t want there ever at all to be a barrier of entry to anything I do,” he said. “I think all art should be in the public realm, free for everyone, all of the time.”

Smith added that they also have been issuing postcards and fliers to inform the public about the work.

“The demographic here is so diverse that not all of them have smartphones,” he noted. “I think it’s naive to assume that this can exist online and nowhere else. We really made a fundamental point of having access to everything regardless of age, social status, access to equipment,” he said.

The reading room exhibit is set to be on display for the next six months, with a possible extension. In addition, during 2018, the library will hold events for the public to further the 50th anniversary celebration. For more info on JML50 visit: https://www.jefferson.market .