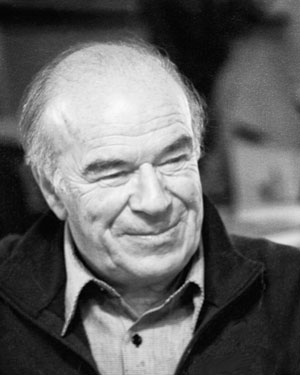

BY JERRY TALLMER | The author of “Disrobed” was indeed disrobed. On this Saturday morning the honorable Frederic Block, senior judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (which covers Brooklyn and Long Island), had set aside his black robes in favor of a light-blue, bicycle-imprinted T-shirt and white shorts.

The traffic on the West Side Drive had thrown him for a loop.

“Cyanide on the rocks with a twist,” he said to a waiting waitress, but then settled for a bagel and coffee.

“So? Did you read the book? How’d you like it?” Judge Block asked this reader. I said I liked it fine but that its index was all screwed up. He said they were working to fix that in the next edition.

“Disrobed” (published by Thomson Reuters Westlaw) is in fact just what its subtitle says it is: “An inside look at the life and work of a federal judge.” Its 454 jam-packed pages carry Greenwich Villager Frederic Block from cradle in Brooklyn (June 6, 1934) through an upward-rising 30-year law career on Long Island to appointment (July 22, 1994) by President Bill Clinton to the federal bench, and everything before and since.

On the back cover of “Disrobed” there is even a nice blurb by President Bill Clinton — “No,” says the bagel-eater, “we’ve never actually met” — regarding Judge Block’s “engaging, often humorous…introduction to the world of a federal judge whose decisions are subject to plenty of public scrutiny but whose decision-making process remains a mystery for most Americans.”

Plenty of public scrutiny? How about the Crown Heights race riots of August 1991, which set the entire city boiling and ended up a dozen years later in Judge Block’s courtroom with the third trial of Lemrick Nelson for the murder of rabbinical student Yankel Rosenbaum.

After four days of fruitless deliberations by the jurors, with Judge Block thinking, “My God, don’t tell me there’s going to be yet another trial,” he sent them home one last time. The next day — August 20, 2003 — they came in with a verdict: Lemrick Nelson guilty, not of murder but of violating Yankel Rosenbaum’s civil rights.

From the “Disrobed” chapter on Race Riots: “I sentenced Nelson to 10 years. It was the maximum under the law…[and] an easy call.”

Not so easy was Judge Block’s reaction when he opened the newspapers the next day and saw that “I was vilified by a columnist for the New York Post… [I]n his article…Steve Dunleavy wrote that he was ‘still reeling from the message given by wacky jurors and a judge who sent them up a blind alley…spitting in the face of a more sensible jurist.’

“I have no idea what he was talking about,” says Frederic Block in his book — and now, over his Saturday-morning bagel and coffee, was interested to hear from this former New York Post slave that Steve Dunleavy was, or had been in my time, one of publisher Rupert Murdoch’s jovial, unscrupulous Australian pets. In short, that any opinions uttered by Dunleavy could be considered Murdoch’s opinions.

“Stupid comments,” the judge now muttered, half under his breath. “Stupid and irresponsible.”

But maybe not as, shall we say, irresponsible as the front-page “wood” — the huge, front-page, 72-point headline — in the New York Daily News the morning after Judge Block’s declaration during the 2007 murder trial of a Queens-based thug named Kenneth (“Supreme”) McGriff that for the government “to seek McGriff’s execution” would be “absurd” and “a total misappropriation” of taxpayer funds.

That Daily News wood, the next day: “JUDGE BLOCKHEAD.”

“It’s stupid and dangerous,” says that judge again, “but what are you supposed to do? You have to live with it.”

Does any of this work — your decisions — ever get to you? I ask the judge.

“No… Well, sometimes. If you have a doubt, your mind keeps working. It bothers you. But as a general proposition, no.”

Pauses. Then: “I gave that Carreto boy [convicted of overlording the white slavery of young Mexican-born prostitutes] 50 years. I was going to give him 35 years, but he showed no remorse for his victims, so I tacked on 15 years. Just could not tolerate the way he behaved. It was a proper sentence, but…a little on the heavy side… .”

A little on the light side are sentences that bring out the quality of mercy, strained or unstrained. For instance in the matter of Aaron Myvett, a wrongo who’d never known a father or had any other break in life. Myvett had made the government happy by turning state’s evidence in a drug case, but could still have received up to 20 years in prison. On sentencing day he showed up in court with astonishing drawings of Mother Teresa and some of Myvett’s fellow inmates.

“Everyone did a double take… . I was intrigued. I adjourned the sentence to explore with the Probation Department whether there might be some way to give Myvett an opportunity to exploit his talent during [a five-year] term of supervised release.”

The way was found: a Catholic school where Aaron Myvett would decorate the kindergarten with Disney cartoons. He also gave Judge Block a likeness of Judge Block. It hangs by the Judge’s desk to this day.

What are the risks — of violent assault, up to and including murder, in or out of the courtroom — faced by federal and other judges every day, every night?

Not many, but enough. After he’d been visited one day by an F.B.I. agent “who looked like he came right out of central casting” and conveyed to the judge the news that a mobster named Anthony (Gaspipe) Casso “had sworn to kill me,” Frederic Block thought he’d better do a little research into “whether I would be the first federal judge who would be assassinated.”

And found out that “if Gaspipe had his way, I would be the fourth during the last two decades.”

So what do you do, mentally, in the face of such risks? Like Samuel Beckett’s two eternal tramps in “Waiting for Godot,” you just go on.

“I feel badly about only one thing. My innocent grandchildren, Jordan, Kyra, Kelsey, Brandon and Ryan, have to go through school being called Little Blockheads.”

The great-grandfather of those five children — the judge’s father — was Norman Louis Block, “always just called Lou,” and their great-grandmother was Florence Ferman Block.

Lou Block started out “in the clothing business, inexpensive men’s clothing,” and then went into the more fruitful telephone-answering business, which took the family out to Long Island.

One of the judge’s two brothers, Leonard, is still alive and kicking at 87. Their brother Sheldon died far too young at 39.

Frederic Block got his B.A. from Indiana University in 1956, his L.L.B. from Cornell University in 1959. From 1961 to 1994 — 33 years — he practiced law on an ascending scale at Patchogue, Port Jefferson, Centereach and Smithtown. Indeed the first 120 pages of “Disrobed” may teach you more about 33 years of Long Island law offices, law cases and (mostly Republican) politics than you ever wanted to know, climaxing in Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.) recommending Frederic Block’s appointment to the federal bench, on the advice of highly respected New York legal eagle Judah Gribetz.

But that section of “Disrobed” will also surprise you — or did me — with the information that from May 22 to June 15, 1984, an amiable, suburbia-slanted, little Off Broadway show called “Professionally Speaking,” music by Frederic Block, lyrics by Frederic Block, produced by Frederic Block, ran for 37 performances at St. Peter’s Church, Lexington Avenue at 55th Street, where the York Players are presently ensconced. The press agent had been my old acquaintance Shirley Herz.

“We tried it out first in Port Jefferson,” says the Frederic Block who looks rather like a onetime professional wrestler some years on. “We got good reviews. Then one day I received a call from Tony Tanner” — the British-born actor-director. “I put on a suit and went to see him. He met me in an orange bathrobe” — and became the director of 1984’s “Professionally Speaking.”

It was when Frederick Block was appointed to the bench that he moved to Manhattan — first to West 77th Street, across from the side entrance of the Museum of Natural History, then to King Street in Greenwich Village, then (and ever since) to the far West Village near where I first lived many years ago.

Frederic Block’s children — variously the parents of those grandchildren — are Neil, age 50, a labor lawyer on Long Island, and Nancy, 49, a social worker in Oregon. He is divorced from their mother after 47 years of marriage — and, according to the book, after sessions over many of those years with no fewer than seven marriage counselors and several shrinks.

Yes, he has a girlfriend — Betsy, “the wonderful Greek-American girl” to whom the book is dedicated. Indeed, even as we talked, Judge Block was preparing to visit Greece “and meet the U.S. ambassador there and give him a copy of the book.”

There is a United States courthouse smack at each end of the Brooklyn Bridge, Judge Block works on the Brooklyn side — in addition, of course, to the home in Greenwich Village where he will often start writing at 2 or 3 o’clock in a sleepless morning.

He gave forth with this book, he says, all by computer and all by himself. The vast source material was “newspapers, my opinions, transcripts of trials, decisions that I wrote.” Not to mention sheer memory. He draws breath, then says, à la Proust: “I was able to recapture my past.”

No, he says, you didn’t have to be a registered Democrat to get Pat Moynihan’s nod, or Justice Judah Gribetz’s boost, or Bill Clinton’s stamp on one’s appointment to the federal bench, but “Yes, I’m an Obama supporter, and yes, I think some of the attacks on him are racist in some parts of the country, yes.”

This is a book that, for my money, picks up steam as it goes along, with sections on “Getting There” and “Being There” all leading up to the eminently readable last 200 pages of “Being There,” broken into eight subsections. These are:

Death — i.e., death-penalty headaches, verdicts and entanglements, notably the case of — see above — Kenneth (“Supreme”) McGriff.

Racketeering — with focus on the paparazzi-blanketed trial of Peter Gotti, older brother of the late John Gotti — “the most difficult and lengthy trial which I…ever had.”

Those paparazzi woke up the day that Judge Block’s girlfriend Betsy, turning up as a courtroom spectator in Cartier aviator sunglasses, high heels and short skirt, unknowingly sat herself down among the similarly garbed Gotti female support fringe. But comedy gives way to tragedy when, after Gotti’s conviction, one of that support fringe — Peter Gotti’s own most loyal lover, Marjorie Alexander — checks into a Nassau County motel, ties a bag over her head, and kills herself.

Marjorie Alexander? One couldn’t help thinking of Susan Alexander — the second Mrs. Charles Foster Kane — as so brilliantly portrayed by Dorothy Comingore in you know what greatest of movies.

Guns — a long and far-ranging expository chapter that perhaps may be summed up by its citing from Bob Herbert in The New York Times “that there are 283 million privately owned firearms in America, that someone is killed by a gun in this country every 17 minutes, that eight American children are shot to death every day, and that since September 11, 2001, ‘nearly 120,000 Americans have been killed in non-terror homicides, most of them committed with guns,’ which is ‘nearly 25 times the number of Americans killed in Iraq and Afghanistan.’ ”

Drugs — a chapter built around the prosecution — or persecution? — and ultimate acquittal of Peter Gatien, movie producer and impresario of the strobe-lit, Ecstasy-wreathed, Limelight nightclub in the beautiful, old, onetime Church off the Holy Communion, Sixth Avenue at 20th Street.

It was, as it happens, piratically eye-patched Canadian-born Peter Gatien who’d won my admiration for first producing the then unknown Chazz Palminteri’s one-man 1989 autobiographical play, “A Bronx Tale,” and subsequently backing the 1993 movie made from it, starring Palminteri and (as actor/director) Robert De Niro. The judge nodded, said yes, but that he’d never seen play or movie.

Discrimination — of all sorts, race, creed, color, age, gender, sexual orientation, birthplace (ah there, Donald Trump!), what have you, with special emphasis on the unequal-pay case of Molly Perdue, Brooklyn College women’s sports administrator and women’s basketball coach, 1991-92. Ms. Perdue thought she was worth at least as much as the men’s basketball coach and men’s sports administrator, and the jury — and then Judge Block — agreed with her. She got a healthy settlement.

Race Riots — notably Crown Heights, see above.

Terrorism — among other cases, that of Afghanistan-born, Queens-based Imam Ahmed Wais Afzali, 39, “a large man in a beige suit and white skullcap,” who on March 4, 2010, wept as he “pled guilty before me for lying to the feds about his relationship with [15 years younger] Najibullah Zazi, who had recently pled guilty to participating in an al Qaeda plot to bomb the New York City subways.”

It is worth noting that the politically circumspect Frederic Block takes occasion in this chapter to remark that Guantanamo Bay “[has dealt] a black eye to the American system of justice.”

Foreign Affairs — notably overseeing the distribution to victims of the Holocaust and their heirs, of billions of dollars of looted money and property salted away in Swiss banks by the Nazis.

So, Mr. Judge Block, what advice, if any, can you tender to would-be wearers of the black robe?

“Aaahhh,” he says, and then stops and thinks a long, long thought. Finally:

“You can’t live your life with expectations of being a judge. That’s foolhardy. You just want to be an interesting person in a broad way. Not Broadway,” he instantly edits himself — can’t resist it — “but a broad way. Don’t let money be the center of your life. All paths lead to Rome, but some paths lead more directly. In other words, do it exactly as I did.”

Court’s adjourned.