BY HEATHER DUBIN | Wearing orange low-top Converse sneakers with red socks, jeans and a cream-colored shirt, Daniel Lerner leaned back in his chair, and reflected on his neighborhood. An East Village resident since 1985, the sales representative for Michael Skurnik Wines has witnessed many changes over the years in what feels like a little town to him.

When Lerner first moved to New York in 1983, he lived below Houston St. at Rivington and Essex Sts. During that time, the drug-riddled streets of the Lower East Side were a hot spot for crime, and fear was rampant.

“I used to run home from the subway,” he recalled.

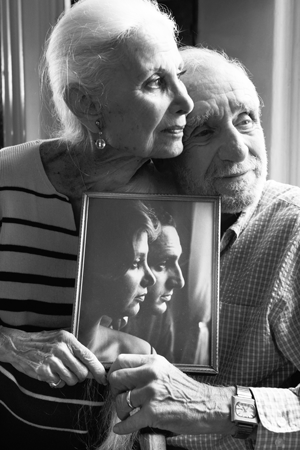

Two years later, Lerner found a two-bedroom apartment in a less rat-populated location on Second Ave. and Second St., where he currently lives with his wife, Kristin Bebelaar.

Initially attracted to the East Village for its thriving art scene and affordable rents, Lerner, a Chicago native, quickly took to the area’s lively and communal vibe.

“All of a sudden my horizons were radically expanded socioculturally,” he said. “I was getting exposed to all sorts of great stuff that I hadn’t seen before.”

Lerner spent time wandering around the neighborhood with friends, and going to restaurants and clubs. A favorite was 103 Second Ave., which he described as a 24-hour “snazzy diner,” now Mighty Quinn’s Barbeque.

“We would go and have these incredibly long meals, start at breakfast, stay through lunch and yack endlessly,” he said. Lerner also loved to go to The World, a nightclub on Second St., and local flea markets.

After they had saved up some cash, Lerner and his friends would hit Hawaii Five-O, a restaurant that used to be on First Ave. Elizabeth Murray, a painter, was a part owner, along with some other artists.

“It was a bizarre conceptual thing,” he said. “The chairs had wheels, there was a diving board in a corner and the walls were painted blue. It was like being inside a pool.”

Lerner, 56, has a half-dozen friends who have been in the East Village as long as him, and they still get together. Some may remember Bernard’s, on Avenue C and Ninth St., whose French chef rode his bike to the farmer’s market to buy produce.

“That was at least 20 years ago before anyone was doing that,” Lerner said.

In Lerner’s view, the edge and diversity that once defined the East Village is gone, and he laments its loss. The neighborhood has become cost-prohibitive to struggling artists and political activists, who are the type of people who founded it, he noted.

“When I moved here, it was an expansive demographic group,” he recalled. “It was very warm and welcoming, and also scary and very grubby, which didn’t particularly bother me. But there was a sense of — we all decided to come here and invent ourselves, and we’re fellow travelers. And now, it’s so profoundly unsympathetic.”

A real turning point for Lerner was when Alistair and Catherine Economakis, upon the threat of eviction, bought out their 15 rent-stabilized tenants at 47 E. Third St., between First and Second Aves., in order to convert the entire 11,500-square-foot tenement into their single-family residence. In 2007, the Economakises won a protracted court battle, allowing them to occupy the entire five-story building with their three children.

“They built a mansion for themselves,” Lerner said. “That event was the straw that broke the camel’s back for me in the neighborhood.”

Lerner would have liked to have seen more affordable housing and protections for working people and middle-class families to remain in the neighborhood.

“The homogeneity of the enormous influx of wealth into the neighborhood makes me feel like I live in a luxury housing development,” he said. “Every move is programmed for maximum profit and profitability. The neighborhood used to be for creative people and outcasts, but now apartments on Bond St. sell for $23 million.”

If he could think of anywhere else to go, Lerner would leave the neighborhood. In the meantime, he supports the local economy, and has frequented the same laundromat and shoe repair shop for about a quarter century.

There is a familiarity and energy to the East Village that Lerner loves.

“There are people I smile to on the sidewalk, and I have seen them for 30 years,” he said. “I don’t know who they are, but I’ve been walking by them for 30 years, and now I recognize their kids, too.”

Lerner described the pulse of the neighborhood as a “collective unconscious” that is close to the surface.

While his wife is ready to bolt, for now, the two of them have a deal.

“When the umpteenth bank comes through or the umpteenth storefront, we’ll leave, because the neighborhood won’t exist anymore,” he said. “But as long as some vestige is left in the neighborhood, we’re staying.

“I’ve been walking out the same apartment door for 30 years,” Lerner said, “I never know who I’m going to see, or who I’m going to run into. There’s always that possibility, and it’s a nice feeling.”