BY ZACH WILLIAMS | The week of Labor Day yielded political developments in addressing income inequality that could lead to new laws boosting the minimum wage and narrowing the wage gap between men and women.

Local elected officials announced a bill on Sept. 8 requiring that state contractors disclose their respective rates of pay for both genders. Two days later, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced his support to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour statewide by the end of 2018. The two bills will go before the state legislature once it reconvenes in Jan. 2016.

Though their respective prospects for passage remain uncertain, they do reflect a broader legislative emphasis at the state level this year on income inequality and just how much an hour of anyone’s time ought to be worth.

“Raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour will add fairness to our economy and bring dignity and respect to 2.2 million people, many of whom have been forced to live in poverty for too long,” Cuomo said in a Sept. 10 statement at the Javits Center, where over 1,200 workers, community members and advocates gathered in support of fair pay. The rally took place on the same day that an order by Acting State Labor Commissioner Mario J. Musolino designated a $15 per hour statewide minimum wage for fast food workers (taking full effect by Dec. 31, 2018 in New York City and July 1, 2021 for the rest of New York State).

While this does not guarantee that supporters of the minimum wage will prevail in the state legislature, it does represent an increased legitimacy for the idea of a $15 minimum wage — a notion once relegated to the fringes of political discourse. Vice President Joe Biden joined Cuomo at the Javits Center, two days before 15 members of the state legislature added their political weight behind the proposed increase, by marching with activists as the Labor Day Parade made its way up Fifth Ave., from W. 44th to W. 67th Sts.

Fast food workers have been at the forefront of demonstrations in the past year, advocating “the fight for 15.” Some supporters emphasize that wage fairness extends to gender politics as well, especially considering that women continue to be paid less than men for the same work.

Closing the wage gap between men and women requires legislative action in more than one way, according to State Senator Brad Hoylman, who represents Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen. Increased transparency would encourage more equitable treatment of employees while also better informing the public at-large as to how local economies reflect the national disparity in pay between men and women, he said in a Sept. 11 telephone interview.

The bill he announced on Sept. 8, in conjunction with Assemblymember Deborah Glick, would require companies with more than 100 employees to issue public reports of mean hourly wages for men and women.

Hoylman advocated “smoking out companies that don’t pay fair wages to their female employees” as one method to establish balance.

The federal government already requires similar disclosures from its private sector contractors. Tens of thousands of projects and billions of dollars in state business would promote pay equity, especially if the public knows whether government business is going to companies who pay women fairly, according to Hoylman.

“That’s a lot of bargaining power that New York can use to address this issue,” he said.

Another bill, proposed by Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal, would reward companies that narrow the gap between pay for men and women to within a 10 percent difference. The companies would a certificate of compliance (the legislative equivalent of a gold star), according to the bill.

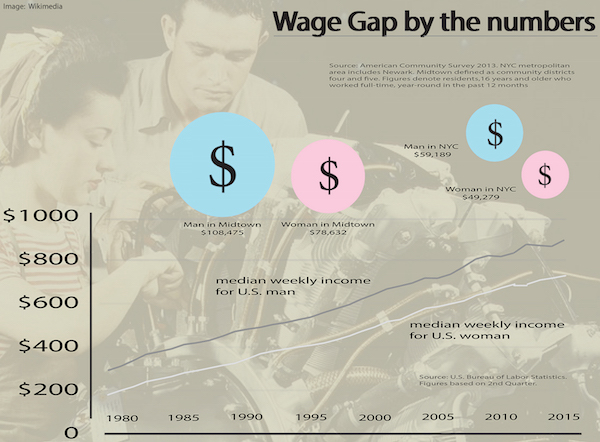

Businesses that pay women more than 90 percent of the wage of a man in a similar position are rare. Public statistics outline a wide wage disparity at the local, city, state and national levels.

Women who have full-time employment make 78 cents for every dollar made by an American man, according to a Spring 2015 report from the American Association of University Women called “The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” (aauw.org/research/the-simple-truth-about-the-gender-pay-gap). Employers in New York actually performed the best (86 cents for every dollar) compared to those in the 49 other states, according to the report, which based its findings on 2013 data.

The data tells a story defying explanations beyond inequality, according to the report.

“In part, these pay gaps do reflect men’s and women’s choices, especially the choice of college major and the type of job pursued after graduation… Yet not all of the gap can be ‘explained away,’” states the report.

A 12 percent difference in earnings remains unexplained for women and men 10 years after their college graduations — even after criteria such as major, occupation, and hours worked are taken into consideration, according to the report. Latinas only make 54 cents for every dollar made by a White man, and 90 cents compared to Latino men, the report notes. Black women make 91 cents compared to their Black male counterparts and 64 cents compared to White men.

Perhaps the starkest statistic comes from a 2014 report (iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-gender-wage-gap-2014-earnings-differences-by-race-and-ethnicity) from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. At the current rate of change, parity in pay for men and women would not arrive until at least 2058, according to the report.

The consequences of such a lingering social phenomenon can be felt 52 years after the passage of the federal Fair Pay Act that ostensibly requires equal pay for equal work.

“My four-year-old daughter started kindergarten two days ago,” Hoylman said in the Sept. 11 telephone interview. “It’s appalling to me that she is already behind her male counterparts on day one, simply because she is a girl. Statistically, she is going to make less than the little boys in her classroom if things remain the same.”