BY JUDITH MAHONEY PASTERNAK | The legendary Judith Malina, co-founder of the Living Theatre, died April 10 at the Lillian Booth Actors Home in Englewood, New Jersey. She was 88.

Diminutive in stature, immense in her influence, a passionately committed pacifist and anarchist who respected no rules, but cherished everything and everyone human, Malina spent a lifetime smashing convention and breaking new ground on the world’s stage and in her personal — but never private — life. The theater company she founded with her first husband, Julian Beck, was a major force in the growth of the artistically innovative and often politically challenging anti-commercial movement that became Off and Off Off Broadway.

Her political activism, on and off stage, landed her in more than one jail. The first of those occasions put her in a cell for 30 days with Catholic Worker co-founder Dorothy Day. She observed Jewish rituals while cheerfully breaking many of the commandments. Her marriage to Beck was non-monogamous, and her pleasures famously included smoking pot.

Malina and Beck founded the Living Theatre in 1947. They started with relatively conventional productions of works by Bertolt Brecht and Jean Cocteau. But in 1959, their production of “The Connection,” playwright Jack Gelber’s searing drama of addiction, won “the Living” its first Obie award and its leading place in New York’s avant-garde and experimental theater.

By 1963, when it produced Kenneth H. Brown’s anti-militarist “The Brig,” the Living Theatre had dedicated itself to politically committed theater, from which it never retreated. The same year saw its first round of trouble with the federal government, when the Internal Revenue Service padlocked the troupe’s theater at 14th St. and Sixth Ave.

The company went on to worldwide fame and ever-increasingly improvisational, participatory, intensely political and occasionally nude productions, from “Paradise Now” in 1968 to its 21st-century cri de coeur against capital punishment, “Not in Our Name.”

Beck and Malina were arrested in Brazil — for marijuana possession, which they denied — and the company was expelled from more than one country. Yet before the end of the century, the troupe had become known across the globe as a symbol of resistance and hope.

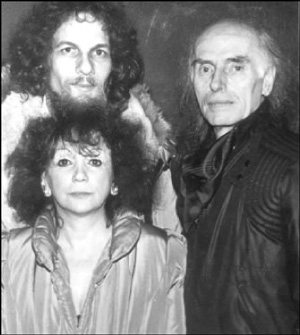

Moving from home to home over the years, buffeted by intermittently acute financial and tax problems, the Living Theatre nevertheless survived. And always, for 68 years, it existed under Malina’s leadership, first shared with Beck, and then, after his untimely death in 1985, Hanon Reznikov, who had been her lover during her marriage to the bisexual Beck and who became her second husband in 1988. Reznikov co-managed the Living Theatre with her until he died in 2008.

Judith Malina was born in Kiel, Germany, in 1926, the daughter of an actor and a rabbi. She grew up in New York City, where her family arrived when they left Germany in 1929. She studied acting at the New School for Social Research with Erwin Piscator, one of the advocates — along with Bertolt Brecht — of the politically charged drama called “epic theater.”

Malina and Beck met in 1943. He was a painter, a year older than she was, but he rapidly came to share her interest in theater, which led them to create the Living Theatre four years after they met.

By then, she was a committed pacifist and anarchist. In 1955, before the young Living Theatre had made headlines, Malina was arrested — for the first time — with members of the pacifist War Resisters League and the Catholic Worker in City Hall Park for refusing to leave the park and go to a bomb shelter during one of the civil-defense drills of the time. She served 30 days for her civil disobedience, sharing a cell with Dorothy Day, now a candidate for canonization by the Catholic Church.

Years later, she told an interviewer that Day’s interactions with the prostitutes and drug addicts who comprised most of the jail’s inmates had taught her that “anarchism is holiness,” because it treats all people as holy, without “dividing [them] into good ones and bad ones.”

By the mid-Sixties, as the Living Theatre became as much an activist project as an artistic one, the two threads of Malina’s life became one. For the rest of her life, her politics were expressed primarily in the company’s works, many of which she wrote. It was an occupation only occasionally interrupted by her forays into film and television. She played Al Pacino’s mother in “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975) and appeared in “Radio Days” (1987), “The Addams Family” (1991) and “Household Saints” (1993). On TV, she appeared in “The Sopranos,” in 2006.

After Reznikov died in 2008, Malina went on to lead the company alone, until their then-current home on Clinton St. closed and she moved into the assisted-living facility in Englewood in 2013.

She is survived by her children, Isha Manna and Garrick Maxwell Beck, and by her other child, the Living Theatre, now under Garrick Beck’s direction and still very much alive, if aging — 68 and counting — and perhaps less robust than its glory days in the Sixties and Seventies. But the ink devoted to Malina’s death is ample evidence that she will remain a formidable presence in the Living Theatre as long as it survives — and in theater around the world, as long as it survives.

The Jewish Daily Forward wrote that one of Malina’s last public appearances was in December at the Bowery Poetry Club. She was in a wheelchair and breathing with the help of an oxygen tank as she read a poem about Eric Garner, the African-American man from Staten Island who died in a police chokehold last summer. Malina’s reading was followed by chants of “I can’t breathe.”