Downtowners are looking for new ideas to deal with the modern problems affecting New York City’s oldest neighborhood.

BY COLIN MIXSON

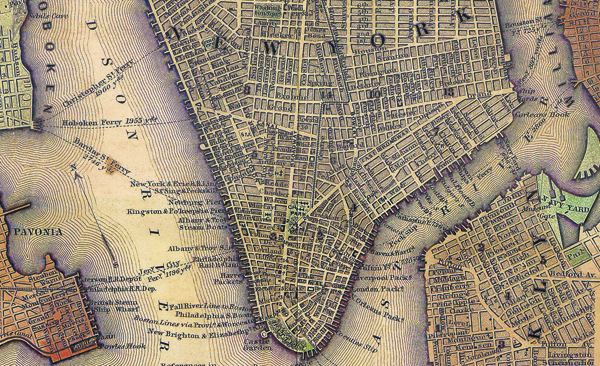

Being the fastest growing neighborhood of the greatest city in the world can be difficult for a part of town that took shape nearly 200 years before anyone even came up with the idea of a Manhattan street grid — and Downtowners are heading to City Hall next week to demand the Council finally acknowledge that fact.

The narrow, chock-a-block, 300-year-old street network of New York’s oldest neighborhood was designed for horses, buggies, and the occasional wheelbarrow, not the thousands of cars, box trucks, double-decker tour busses, and garbage haulers that now ply its slender lanes, and for more than a decade, Community Board 1 has asked the city to fund a comprehensive study of the many interconnected logistical challenges unique to Downtown.

But though the city has addressed specific problems caused by the essentially medieval Downtown streetscape, it has failed to attack the systemic problems in a holistic manner that takes into account how they overlap and complicate each other. Now, both Community Board 1 and the newly formed Financial District Neighborhood Association are gearing up to petition City Hall to include money in next year’s budget to fund studies aimed at addressing the myriad obstacles that the 21st century holds for a 17th century neighborhood.

“No agency or entity has proposed anything to address the changing needs for CB1, to address the continuing intensifying vehicular and pedestrian flow on our narrow streets and cluttered sidewalks,” said CB1 chairwoman Catherine McVay Hughes. “A comprehensive study and implemented plan could address major quality of life issues.”

Reps for the community board and neighborhood association will appear before the Council at the executive budget hearings on May 24, where they’ll present their case for funding a Department of Transportation feasibility study.

Ever since the terrorist attacks on 9/11, and the reconstruction and safety measures that followed, CB1 included funding for traffic studies in its yearly budget requests, according to the board’s director of planning and land use, Diana Switaj.

But those requests have gone unheeded, and since then, the area has seen massive residential and hotel construction, with the Financial District in particular becoming the fastest growing neighborhood in the city.

Next Tuesday’s hearing will be the first time in recent memory that representatives of the board have appeared before city council in person with a budget proposal, and they hope to hammer home the fact that Downtown’s traffic problems can no longer be ignored.

“By appearing at the budget hearing, we’re saying we’ve made these requests for years and we’re drawing attention to the fact that our needs haven’t been met,” said Switaj.

Both CB1 and the Financial District Neighborhood Association’s presentations will be informed by Make Way for Lower Manhattan, a detailed examination of the challenges unique to Downtown commissioned by the engineering firm Burohappold.

The study notes particular factors contributing to Downtown’s traffic woes, including its explosive growth, which has doubled since the start of the millennium — both in terms of visitors, from 6.5 to 13 million, and residents, from 34,420 to nearly 70,000.

The assessment highlights the narrow width of streets and sidewalks in Lower Manhattan — such as William St., with 14 feet of roadway flanked by 10-foot wide sidewalks — compared to roadways uptown, where avenues average at least 60 feet wide, with cross streets running about 30 feet, and both with 15-foot sidewalks.

Make Way for Lower Manhattan also looks to cities in Europe and elsewhere with similarly medieval street layouts, such as London, Melbourne, and Barcelona, for ideas on ways to deal with traffic and municipal service challenges.

In Barcelona, for instance, parking problems have been curtailed by limiting parking to residents, taxis, hotel guests, and emergency services at certain times, while traffic in the city’s iconic La Rambla boulevard is eased by limiting access to cars during specific hours. London’s Oxford Street was similarly liberated from traffic by restricting access to red busses and black cabs only.

Patrick Kennell, president of the Financial District Neighborhood Association, plans on pointing to the British capital as evidence that streetscapes like those found Downtown can be developed responsibly with smart policies.

“So what London does that I particularly have noticed is you never see trash anywhere on the sidewalks,” he said. “The sidewalks are filled with people just like they are here, but you never see piles of garbage lying around, you never see the garbage trucks coming around, that all happens while people are asleep. There are delivery zones, places where there’s no parking, because traffic needs to get through and the streets are fairly narrow.”

Kennell contends that Downtown’s various congestion woes create a domino affect contributing to a vicious cycle of diminishing quality of life, where traffic affects garbage pickup, which leaves piles of trash on the narrow sidewalks, which forces pedestrians to walk on the street, which in turn stalls traffic, and so on.

Therefore, to alleviate Lower Manhattan’s interlocking problems, the city needs to tackle Downtown’s congestion issues as a whole, not one at a time.

“They city knows it’s a problem, but they’ve tried to treat it by addressing single problems, pockets of areas,” he said. “They haven’t treated the whole thing.”