BY SEAN EGAN | This week, the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) approved plans for construction on 334 W. 20th St. (btw. Eighth & Ninth Aves.), which would build the rear of the house out, and, according to critics, detrimentally affect the character of the block and encroach on green space. These opponents came out in full force at the Tues., Sept. 13 LPC hearing where the decision was made — a dozen strong, and clad in green shirts that served to silently air their grievances.

The building, an 1836 Greek Revival style row house, sits within the Chelsea Historic District, making any changes subject to LPC approval. At the project’s initial Aug. 2 LPC hearing, the applicant, Sterling Equities, presented plans that would include a large rooftop addition and bulkhead, as well as a significant rear yard extension. The hearing found a few block residents come out in opposition — many of whom populated the Sept. 13 hearing — including Carol Ott, the president of the 300 West 20th Street Block Association, and Rev. Stephen Harding from the neighboring St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. Their ire stemmed from the short notice they were given about the project, its size, the rooftop addition’s visibility from the street, and the way it would affect neighbors’ connected corridor of lawn space.

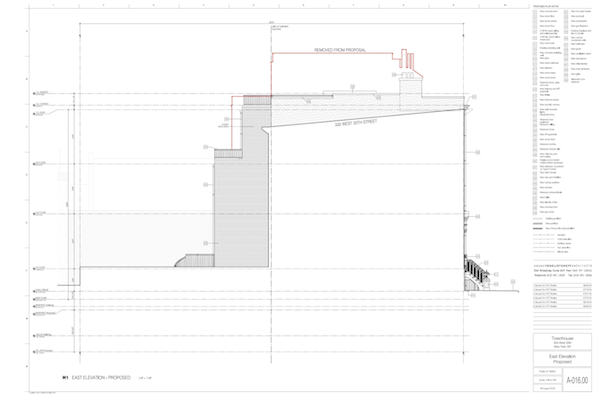

LPC Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan agreed, and requested that the roof addition be scrapped altogether and that the third floor be set back to the historic line/openings to ensure the building’s legibility. The LPC decided not to take action at that time, asking the Sterling team to come back at a later date with plans incorporating their feedback.

The issue was raised again at the Sept. 7 Community Board 4 (CB4) full board meeting, where the board was scheduled to vote on a letter to the LPC concerning revised plans for the house. An increased number of advocates participated in the public comments session, to express that even the altered plans — which ditched the rooftop addition and scaled back the rear — were inappropriate. Upset residents (again, donning lime-green T-shirts) testified to how the project would alter the block’s backyard “donut” area of green space and their views of landmarks like St. Peter’s, and how it would set a bad precedent, allowing other houses in the area to whittle away the character of the block.

Once more, Ott stood in opposition, claiming “the plans transformed a sweet…property into a behemoth.” Many others took to the podium to advocate for the preservation of the “magical space” and “little gem” that is the backyard area, which represents some all-too-rare green space in Chelsea. Others called the project “overpowering” on the “prettiest block in New York City.” All such comments drew rapturous applause from the crowd.

Sterling’s architect, Andre Tchelistcheff, spoke, stating that the construction reflected in the new plans was nowhere near as radical as those assembled (who referred to the building as a “mini-mansion”) believed it to be. He also highlighted the historic façade restoration work his client planned on doing, predicting that when the project was done, “I know the block would be proud to have us as a neighbor.”

During a post-meeting phone interview, project reps told Chelsea Now that they were only seeking to add 1,176 sq. ft. to a 4,700 sq. ft. property — a far more modest, 25% increase in size compared to the doubling neighbors claimed would take place.

At the end of the meeting, CB4 member Lee Compton noted that while the community was upset, the updated plans — particularly the 14-foot build-out of the first two floors — were “as of right,” meaning that they complied with applicable zoning regulations for the area and were not visible from public thoroughfare, and thus were not an LPC concern. Because of this (and CB4’s purely advisory role in these matters), Compton expressed doubts that the community would get its way, despite the board voting to send a “deny unless” letter, asking the LPC to look again into the visibility of the rear extension, and take into consideration the block’s concerns.

Compton’s pessimistic prediction was proven right at the project’s second hearing, as the revised plans were quickly approved.

“This is a very important little piece of the historic district,” Srinivasan said, noting that the new plans took great steps forward in nixing the rooftop entirely, and were “almost there, but not quite there.” The lone issue she and the rest of the commissioners took issue with was the extension on the third floor — which, unlike the lower two floors would push seven feet out (about 171 sq. ft.), and would still be visible from the street. While the size was reduced from initial plans, they did not abide by the LPC’s earlier request to fully restore the floor to its existing, historic line. While Tchelistcheff argued that an extension of that size was not unprecedented in the area, Srinivasan maintained that the building’s location on the end of the row of houses made the legibility of the historic line of the building crucial to its integrity.

Ultimately, the LPC voted to approve the project’s certificate of appropriateness, with modifications indicating the third floor would not include an extension. It represents the latest in a line of community struggles with the LPC in trying to preserve Chelsea’s character — including, most recently, the approval of plans to effectively demolish all but the façade of 404 W. 20th St., widely acknowledged as the oldest dwelling within the Chelsea Historic District.

“What happens if it’s not just two houses, but eight houses?” lifelong Chelsea resident Sarah Edwards pressed at the CB4 meeting, articulating the crowd’s concerns to applause. “Then there would be nothing left of these historic houses.”