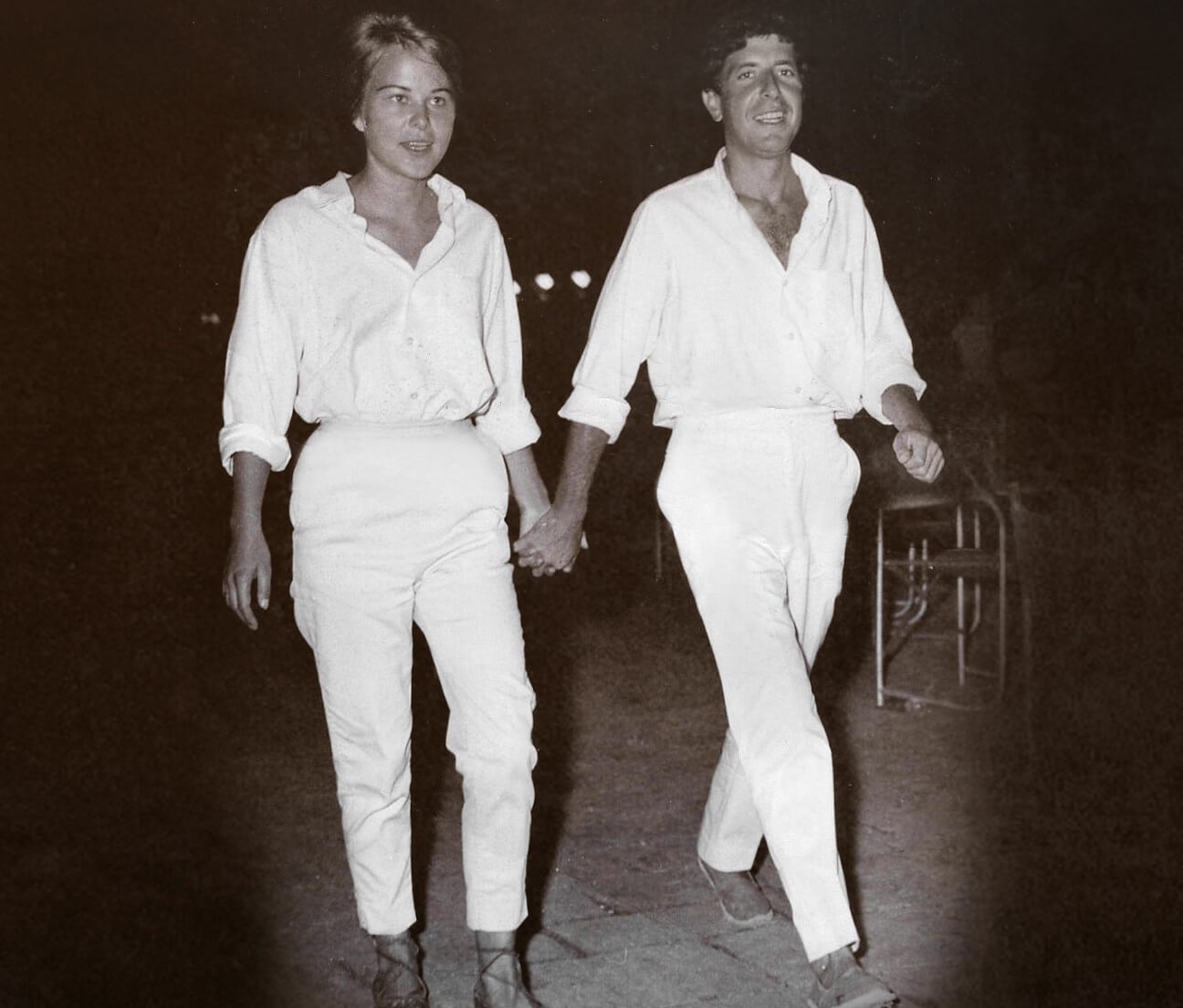

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | The new documentary “Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love” reportedly may not break much new ground for hardcore Leonard Cohen fans. But it nonetheless paints a riveting and thought-provoking portrait of the artist and Marianne Ihlen, his Norwegian “muse,” from their idyllic time together on the Greek island of Hydra in their 20s all the way to the end of their lives.

After achieving notoriety as a poet in his native Canada, Cohen bought a house on Hydra — which sported a bohemian artist enclave — and tried to make a go of it as a novelist. He met Ihlen in a cafe and soon they were living together.

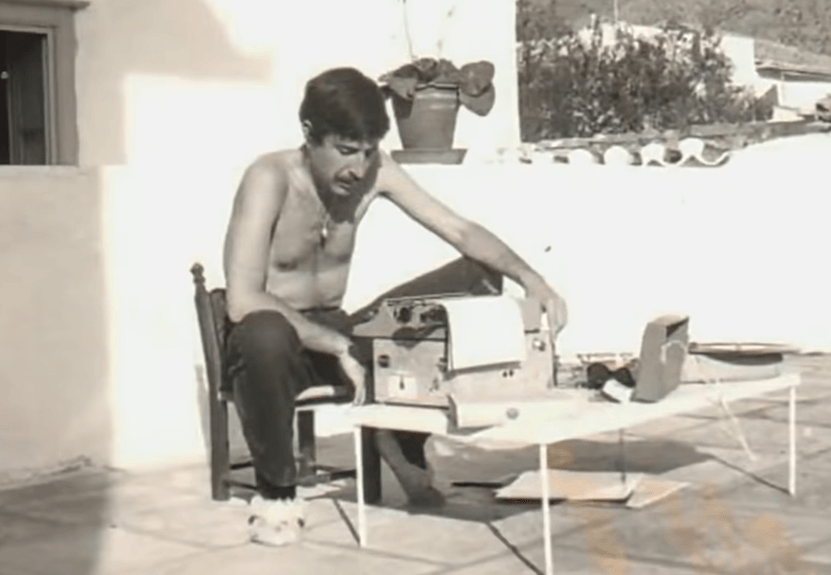

Baking on his porch in the hot sun while hammering away at his typewriter on speed, Cohen cranked out “Beautiful Losers.” Meanwhile, Ihlen did the shopping and adored him.

But the book received mixed reviews.

Instead, Cohen switched to songwriting. With an assist from Judy Collins, who promoted him, his brooding, romantic compositions and inscrutable mystique soon made him a star.

Cohen asked Ihlen to come join him living in New York City, but the doors to fame had been flung open for him, and he jumped through lustily. We learn about how, while Cohen was trysting with Janis Joplin “on an unmade bed” at the Chelsea Hotel, Ihlen was in the dark about it all.

Providing a knowing, humorous commentary on Cohen is Aviva Layton, the wife of his great friend the Canadian poet Irving Layton. Basically, she explains, Cohen is the type of man that all women want — but that none can have. Indeed, Cohen bounced from relationship to relationship throughout his life.

We also learn about how the legacy of Hydra was like a curse for its bohemian artists and their families, who were racked by substance abuse and other problems. A thread of madness runs through the film, starting with Cohen’s mother.

We see entertaining footage of Cohen on tour, showing his lighter, playful side with bandmates, a stark contrast to his stoic stage presence. Ron Cornelius, his guitarist — and a doppelganger for Bill Clinton — recalls they were taking so much Mandrax (Quaaludes) on tour, that one night he literally faceplanted onstage. And then there were the 23 straight nights of dropping acid.

We see a brief clip of Cohen during his Upstate Buddhist-retreat phase, where he is the servant of a seemingly crotchety monk.

The movie’s director, Nick Broomfield, is an experienced filmmaker, known for his documentaries, whose credits include “Monster in a Box,” “Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam,” “Kurt and Courtney,” “Biggie & Tupac” and “Sarah Palin: You Betcha!” among many others.

Broomfield himself also had a short-lived affair with Ihlen, whom he recalls as having a knack for helping people identify their true skill. She encouraged him to get into documentary filmmaking.

The director also artfully uses archival footage of Ihlen sailing off of Hydra by D.A. Pennebaker. These gauzy shots evoke the feel of an earlier, faraway paradise.

It’s hard not to feel a bit sad about Ihlen’s fate. She does go on to return to Norway and marry a Norwegian man and get an office job. Through the years, Cohen continued to invite her to his shows. And we see her in the audience at one show in their later years, smiling and singing right along to his jaunty breakup song to her, “So Long, Marianne.”

The two died just months apart from each other in 2016. Cohen was 82 and Ihlen, 81.

A little online reading reveals that Ihlen gave Cohen the central image for one of his most famous songs, “Bird on a Wire.” She had seen a bird sitting on a telephone line, and said it looked like a musical note, and suggested he do a song about it.

In a side note, after the movie’s release, Bono and his family, while “island hopping,” visited Cohen’s former home on Hydra and posted a photo and slightly doctored lyrics to “Bird on a Wire” on the U2 Instagram page.

This movie gives one a lot to think about, in terms of creativity and relationships, Cohen’s music, career and psyche, endings — and endings that are not really endings — life itself and aging.

We are left with the haunting, somewhat faded and blurry image of Marianne on the gently bobbing sailboat, with the yellow sun burning over the silver-sparkling Aegean sea — a moment in time in two complex lives.

As one filmgoer at the Angelika Film Center recently said, as the credits started to roll, “That was a beautiful film.”