Garden activists really dug what some of the candidates had to say at the April 27 forum.

BY SARAH FERGUSON | New York’s community gardeners were once derided as squatters, even “communists,” for staking out flowerbeds and vegetable patches on city-owned lots. But on Sat., April 27, they were greeted by the city’s mayoral contenders as something else: political stakeholders.

Seven candidates — including frontrunner Christine Quinn, Comptroller John Liu and former Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion — came to The Cooper Union’s Great Hall to present their views on greening and open space at a mayoral forum hosted by the New York City Community Garden Coalition.

While not all turned out — Joe Lhota and Bill de Blasio were last-minute no-shows — the presence of so many candidates was testament to just how far this grassroots movement has come in the last 15 years.

“We want the gardens and their preservation to be an issue in this campaign,” said Charles Krezell, an N.Y.C.C.G.C. board member. “It’s an environmental issue, it’s a health issue. We’re saying, making gardens permanent is a very inexpensive way for the city to help itself.”

In general, all the candidates agreed on the need to preserve and even expand the number of community gardens in the city, though they differed in approach.

Council Speaker Quinn recalled protesting alongside gardeners in 1999 as many risked arrest to stop the auction of green spaces under the Giuliani administration.

Those protests, and a lawsuit by former Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, led to an agreement with the Bloomberg administration to save nearly 200 community gardens threatened by development. But Quinn warned that the legal status of these community-tilled spaces remains nebulous.

“The challenge with what we did is, it’s only as good until the end of Bloomberg administration,” Quinn noted, adding, “We need to make sure that gardens don’t become political footballs in future administrations.”

Quinn advocated placing all gardens in a “land trust” to make them permanent, though she did not spell out how that trust would be administered.

By contrast, Liu said he would put all community gardens under the wing of the Parks Department, because that would ensure a “permanent stream of resources.”

“But we should also ensure that the organization in the community that created the garden in the first place should always have some say in how that garden is maintained and grows,” Liu added, drawing cheers from the audience.

Similarly, former Bronx Beep Carrion, who is running as an independent, said he would “designate gardens as part of our parkland.”

Quinn and Liu also differed when asked to comment about the Bloomberg administration’s willingness to privatize public land and resources — such as the transfer of parkland to build the new Yankee Stadium, the city’s ongoing attempt to install a private restaurant in Union Square, and the proposed transfer of at least two open-space strips in the South Village to New York University.

“It seems like this administration, in its last eight months and three days, is trying to sell off as much property as possible,” said Liu. He pointed to the recent proposal to allow “luxury” development in the open spaces within New York City Housing Authority projects. “That is absolutely wrong,” he said, adding, “Once you sell off a public asset, you never get it back.”

By contrast, Quinn said the city should “minimize” sales of public assets to those instances when “we have no choice.”

“When that does have to happen, and the developer makes real promises of other land or other compensation, we have to have real clawbacks built into those deals, so if they don’t follow through, there are real penalties and real repercussions,” she said.

All the candidates advocated expanding funding for Parks to “green” the city.

“We can’t want to be the greatest environmental city in the world” without a “robust and fully funded Parks Department,” Quinn noted.

But Liu was more specific, saying he would add $310 million a year to the Parks Department’s coffers simply by taxing insurance companies, which are currently exempt from general corporation tax in New York City.

In general, Liu received more support from the crowd, while Quinn drew a few jeers from those audience members critical of her financial backing from real estate interests. Carrion was loudly heckled for his role in overseeing the Yankee Stadium deal.

There was plenty of green visioning from the other candidates.

Green Party candidate Tony Gronowicz said there should by a citywide “greenhouse initiative” to stem the obesity and diabetes epidemics.

“We have to restore our connection to nature in every neighborhood,” he said, “and have children learning to grow fruits and vegetables from an early age.”

Likewise, Carrion advocated a network of “urban vertical farms” to supply the city with fresh produce and build a “green collar economy.”

And George McDonald, the Doe Fund president, pledged a “garden on every rooftop” supplying food to schools and communities, and the expansion of other green initiatives to create a “full-employment economy.”

“Why can’t we spend a few pennies more to make apple sauce in the Bronx?” he asked.

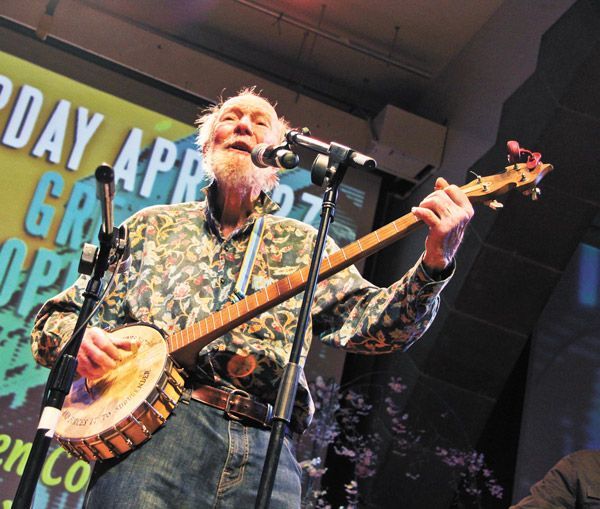

But for many who attended, these would-be mayors were just a warm-up act for headliner Pete Seeger. The folk singer and environmentalist, who turned 94 last week, brought the audience to its feet when he launched into his classic anthem, “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

“To everything, there is a season,” the gardeners sang along, many with tears in their eyes. Seeger even debuted a few verses that he had penned years back for his children.

After receiving an engraved hammer from organizers — and leading a raucous sing-along of “If I Had a Hammer” — Seeger praised New York City gardeners for pioneering new models of sustainable urban living.

“If we do our job right, 200 years from now, they will look back to this day when you showed people how planting gardens will bring people together,” Seeger said.

For many in the house, it seemed like that milestone had already arrived.