BY ANDREW BERMAN | Sometimes you don’t want to be right. One of those times was at the Feb. 12 Land Use Committee meeting of Community Board 2. It was there that Madelyn Wils, the Hudson River Park Trust’s president, finally provided an answer to a question I and others had long been asking about the Hudson River Park air rights provision passed by the state Legislature in 2013.

Wils acknowledged that, yes, as we had feared, the legislation did arguably create many more transferable air rights, and from a much broader swath of the park, than we were originally told — not only from the nine “commercial piers” within the park (ones like Chelsea Piers, where some commercial development is allowed and there is little or no park space), but from the more than a dozen other recreational-use park piers, as well.

In effect, this means that, in addition to the roughly 1.6 million square feet of air rights we were originally told the legislation allowed to be transferred inland for new development, the new law actually creates hundreds of thousands, and possibly millions, of additional square feet of air rights and development potential.

Wils tried to assure us all that this would never happen — that neither she nor the city would ever entertain the use of air rights from these noncommercial piers. That was nice to hear, but as the old saying goes, that and a token gets you on the subway.

Neither Wils nor any of the other current players will be in charge of their respective agencies forever; even if they were, a verbal assurance such as this is hardly a guarantee, especially when hundreds of millions of dollars of potential real estate development and profit are at stake. And certainly in recent years we have seen many city officials go back on their word and approve land-use deals that they not only pledged to oppose, but that we might have never dreamed possible.

This is a vivid reminder that the air-rights legislation passed by our local state legislators creates an enormous potential for vastly increased development along our waterfront. A certain, limited use of air rights to generate needed revenue for the park might be appropriate in some cases. But the legislation currently simply creates a vast pool of possibilities, and leaves it up to city officials to decide how and when they can be used — city officials who have, in the past, given us the N.Y.U. expansion plan, the St. Vincent’s/Rudin rezoning, and the Chelsea Market upzoning.

That is why it is critical that we insist that safeguards and limits be put in place now to prevent future overuse and abuse of this open-ended air-rights provision, and to protect our neighborhood from overdevelopment.

The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, along with a coalition of Village, Downtown and Chelsea community groups, including the Council of Chelsea Block Associations and Greenwich Village Block Associations, representing nearly every block association in those areas, as well as nearly every Democratic club from Chelsea to Tribeca, are calling for three principles to be included in any plan for moving ahead with use of air rights from the park.

First, extinguish all air rights from the noncommercial piers. If, in fact, no one ever intends to use these air rights, this should be a no-brainer. There is no reason why park piers, which are actual park space, should have development rights that can be transferred inland. The same state legislators who approved the original air-rights plan — Assemblymembers Glick and Gottfried, and state Senators Hoylman and Squadron — should draft and pass new legislation that disallows air-rights transfers from these piers and other parts of the park. And the City Council and City Planning Commission should rezone those parts of the park to eliminate any development rights.

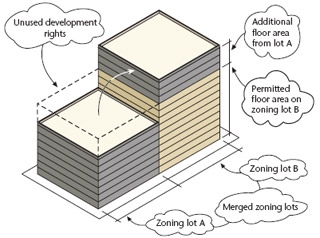

Second, pursue measures to fund the park without upzoning our neighborhood and increasing development along our waterfront. Perhaps the scariest thing about the air-rights transfer plan is it makes funding the park dependent upon increasing the size of allowable development in our neighborhood, above and beyond the already substantial size of development currently allowed. But there are ways to fund the park without upzoning and overdeveloping our neighborhood. These include assessing a fee on all new nearby development to fund the park; pairing any air-rights transfer with a downzoning, so that the allowable amount of new development is not increased as a result; and attaching air-rights transfers to a change in allowable use, rather than an increase in allowable size (i.e. allowing development of a 10-story residence instead of a 10-story hotel as part of an air-rights transfer, rather than increasing the allowable size of a hotel development from 10 to 15 stories, as the current thinking would require).

Third, make any use of air rights dependent upon meeting agreed-upon definitions of financial need for the park. The purported purpose of the air-rights legislation is to fund the construction and maintenance of the park, but the amount of air rights created could generate vastly more revenue than necessary for doing so.

Currently, there is nothing in the legislation saying that air-rights sales must stop when the park’s financial “needs” are met. Therefore, it is critical that a standard be established for defining what the park’s real financial “needs” are that the air-rights sales are supposed to address. No air-rights sale proposal should be allowed to advance through the public review and approval process if it does not first meet this established “needs” test.

Now will likely be our one chance to put in place the limitations needed to ensure that air-rights sales are not misused in the future and do not result in overdevelopment of our waterfront. If we don’t insist upon these measures from the beginning, we are setting ourselves and our neighborhood up for disaster. Powerful real estate forces can and no doubt will find a way to ensure that every one of the millions of square feet of development that this legislation allows in our neighborhood is used. And once approved, it will be impossible to reverse.

Berman is executive director, Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation