by John W. Sutter

New York University is planning to apply for a major rezoning of its two South Village superblocks, which, among other things, would allow it to build a planned tower up to 38 stories tall — which would be half residential and half hotel — on its southern superblock.

The two extra-long, N.Y.U.-owned superblocks are located between W. Third and Houston Sts. and LaGuardia Place and Mercer St.

Without the rezoning, N.Y.U. would only be able to build the tower half as big, since the block’s current zoning doesn’t allow that much residential development; N.Y.U. also would be unable to include a hotel in the tower, since the block’s current zoning forbids transient hotels.

Also part of the plan, N.Y.U. is seeking to demap and acquire narrow strips of property currently owned by the city’s Department of Transportation on the sides of the superblocks along Mercer St. and LaGuardia Place.

The Villager learned about the proposal — which would change the megablocks’ zoning from R72 to C62 — when it was recently leaked to the newspaper by a community member on the Borough President’s Community Task Force on N.Y.U. Development. The task force’s discussions are supposed to be confidential.

Told that The Villager was aware the proposal was for a C62 rezoning, Alicia Hurley, N.Y.U.’s vice president for government affairs and community engagement, agreed to meet with the newspaper to explain the plan’s details accurately.

Joining Hurley at the meeting with The Villager last Thursday were William Haas, N.Y.U.’s planner; and Bob Davis, the university’s outside land-use counsel.

Though their hand was forced by the task force leak, Hurley stressed the university hadn’t intended to make the plan public yet.

“This is a very sensitive time for us,” she said of the rezoning, which is certain to draw fire from community opponents.

Although N.Y.U. has commenced discussions about the rezoning with the task force, it hasn’t shown the plan to the Department of City Planning yet. Right now, Hurley said, the university is “exploring ideas,” and the plan isn’t finalized.

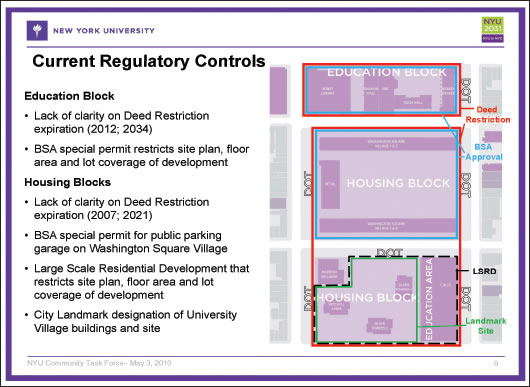

At the meeting with The Villager last week, the three first laid out the complicated history of the superblocks, which also include the smaller N.Y.U.-owned superblock to the north, between Washington Square South and W. Third St., home to N.Y.U.’s Bobst Library.

‘Slum,’ but not really…

The three superblocks comprised the Washington Square Southeast Urban Renewal Area, approved in 1954 as a Title I “slum clearance” project. In this case, however, it wasn’t a residential “slum” being cleared — there were less than 140 residential tenants living on the site — but mainly old commercial and manufacturing loft buildings.

To create the three superblocks, Wooster and Greene Sts. were demapped from Washington Square South/W. Fourth St. to Houston St. Also, Mercer and W. Third Sts. and LaGuardia Place were widened to improve traffic flow as part of the city’s plan for a crosstown Lower Manhattan Expressway, which was ultimately defeated.

In 1955, the northern so-called “education block” was conveyed to N.Y.U. via an educational deed, while the two southern superblocks — dubbed “housing blocks” — were conveyed from the city to a private developer.

In 1961, the Washington Square Village residential complex was completed on the middle superblock, along with the accompanying, low-rise retail strip on LaGuardia Place, plus the supermarket across the street at the corner of LaGuardia Place and Bleecker St.

In 1963, the Washington Square Village superblock was sold to N.Y.U. by a private developer. The same year, the still-undeveloped southern superblock was also sold to the university by a private developer.

The urban renewal plan was amended four times over the years. In 1958, it was changed to allow construction of the supermarket at LaGuardia Place and Bleecker St. The second amendment, in 1962, designated the southern superblock as “residential,” except for the supermarket site, which was designated “retail.” Following this amendment, in 1964, a large-scale residential development plan, or L.S.R.D.P., was approved for the block, allowing N.Y.U. to construct its three-building University Village (Silver Towers) complex, which it completed in 1967.

In 1966, the plan was amended to allow N.Y.U. to take over the block-long strip of LaGuardia Place between Washington Square South and W. Third St. so it could build its Bobst Library that much wider, and also to construct the library with sheer exterior walls, without the required setbacks.

The last amendment came in 1979, when the southern superblock’s eastern end was designated “educational” to allow development of N.Y.U.’s Coles gym. (Originally, the Coles site was to be a residential building.) Construction on Coles finished in 1981.

Deed needs explaining

Where all these plans and amendments leave N.Y.U. today is basically trying to figure out, first of all, when it could even start development on its superblocks — which is a key component of its 2031 growth plan: As part of its long-range expansion scheme, N.Y.U. hopes to add up to 1.5 million to 2 million square feet of space in its “campus core” around Washington Square, mainly on the two superblocks.

One key question for N.Y.U. is when the deed restriction tied to the urban renewal plan expires. Generally speaking, the expiration is 40 years after the project’s completion — until then, what’s on the ground cannot be altered, and new additions cannot be made. Did the clock start on the deed restriction’s expiration in 1967, when Silver Towers was completed, or in 1981, with Coles’s construction? If it’s the former, then the restriction ended in 2007, and N.Y.U. could start developing on the superblocks, assuming it got the needed zoning changes. But if it’s the latter, then the restriction would still be in effect until 2021, and N.Y.U.’s development plans would have to be put on hold.

Land-use counsel Davis predicted the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development would take the “conservative” view and say the deed remains in effect till 2021. If that’s the case, N.Y.U. would then try to have the restriction modified, he said. H.P.D. can administratively change the restriction, they noted.

“The deed restriction will probably be the simplest thing to be done,” Hurley said. She added the plan will undergo a public review under the city’s uniform land-use review procedure, or ULURP.

The N.Y.U. officials and Davis next proceeded to flesh out the new plan’s details.

Strips takeover bid

First, they stressed that N.Y.U., in taking over the D.O.T.-owned strips, wouldn’t use the air rights from these parcels to add bulk to its development projects. However, the university does want to extend out onto the Mercer St. strip the new academic building it would construct on the current Coles site. In return, as a public amenity, N.Y.U. would widen the alley-like remnant of Greene St. on the Coles site’s west side.

Residential requirement

Currently, the area to the east of the superblocks — between Mercer St. and Broadway — is zoned C62, and N.Y.U. would like to extend that same zoning onto the superblocks, replacing the current R72. This zoning change would increase the residential floor area ratio (F.A.R.) from 3.44 to 6.02. (Floor area ratio is a relation of the property’s footprint to the floor space that can be constructed within the building.) In short, a 6.02 residential F.A.R. would allow construction of the 38-story tower, while a 3.44 residential F.A.R. would be insufficient for a building of that size.

N.Y.U. wants this new fourth tower it would add in its University Village complex to be half for faculty housing and half for a hotel for visiting N.Y.U. faculty from abroad and others, such as visiting parents and students. The block’s current zoning has a 6.5 F.A.R. for community facilities (such as dormitories), which would allow a 38-story tower — but neither faculty housing nor a transient hotel are allowed under this use group.

Under the rezoning, the block’s community-facilities F.A.R. would remain at 6.5, but the allowable commercial F.A.R. would jump from 2.0 to 6.0, which would allow a taller, mixed-use building on the current Coles gym site.

Adding new buildings

Current zoning doesn’t allow new buildings to be added to the southern superblock, neither a fourth tower nor new construction on top of the existing Coles gym.

However, Hurley said, that under N.Y.U.’s proposed C62 zoning, “more of the lot can be covered,” which she acknowledged is “another potential flash point” with opponents. This aspect would be seen at the Coles site, whose 23-foot-tall rooftop is currently considered “open space.” If a bigger building — with a new underground gym — replaced Coles under the plan, this rooftop open space would be lost. The design for the new building’s rooftop is a severe zigzag shape, which would seem to make it unsuitable for recreational use.

However, the Morton Williams supermarket would be moved from the block’s northwest corner to the ground floor of this new building at the block’s southeast corner (on the Coles site), freeing up the former Morton Williams site to be turned into a public open space.

“The nuance here is that we think we can return this to actual open space,” Haas said of transforming the supermarket corner into a public open space.

Hurley and Haas acknowledged that, as part of the superblock’s open-space agreement from decades prior, N.Y.U. was required to create a community playground on the southern one-third of Coles’s rooftop. However, they admitted, due to various access problems — which they didn’t fully explain — this playground “never really worked.”

Hurley noted N.Y.U. is “investigating” exactly what happened with that playground.

The lost playground

According to a brief history of the superblocks that was provided to The Villager, the Coles rooftop playground included “a play fountain, clatter bridge, slides, cargo net, vertical rope swing, play deck, play cubes, kickball area, shade trellises and basketball court.” The basketball hoops, however, were removed the first week the playground was open after a basketball went flying off the rooftop and through the windshield of a car traveling on Houston St.

On the Washington Square Village superblock, the buildings are currently constructed to an F.A.R. of 4.1. The taller of two infill buildings that the university would like to add in the complex’s courtyard, on the Mercer St. side, would have an F.A.R. of 5.4.

Asked why the university is only asking for 5.4 F.A.R. and not 6.5, Haas said, “It’s an attempt to be respectful.”

Current zoning doesn’t allow new buildings to be added in the block’s interior. The two infill buildings — preliminary designs of which Andrew Berman, director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, likened to “Space Mountain” — would extend out onto the Mercer and LaGuardia strips. Hurley confirmed that the smaller of the two infill buildings would poke out right onto the Mercer St. strip where the iconic statue of Fiorello LaGuardia is located, so the “Little Flower” would have to be moved a bit.

The D.O.T. strips are currently 35 to 40 feet wide on LaGuardia and 30 feet wide on Mercer; a 15-foot-wide walkway would be kept, even with the infill buildings projecting out, Haas assured.

Large-scale plan

The commercial area of the low-rise retail strip along LaGuardia Place essentially would be relocated a block south into the new mixed-use building on the Coles site.

To shift these commercial uses around would require city approval of what’s known as a general large-scale development plan, or G.L.S.D.P. — similar to what The Cooper Union did eight years ago when it embarked on its rebuilding plans in the East Village. The G.L.S.D.P. would replace the existing L.S.R.D.P. (large-scale residential redevelopment plan).

In addition, N.Y.U. wants to rezone the blocks to the north of the superblocks and east of Washington Square Park to allow it to add retail uses on the ground floors of its buildings there.

These uses would mainly be “convenience retail — to serve the university community,” Davis explained.

“Not big-box retail,” Hurley assured, adding the shops will be similar to what can now be seen here along Waverly Place.

N.Y.U. also wants to extend the sidewalk 15 to 20 feet into W. Third St. between Mercer St. and LaGuardia Place to align it with W. Third St. to the east and west.

Hotel N.Y.U.

As for the hotel in half of the planned fourth tower that would be added to the Silver Towers complex, Davis said visiting faculty — such as from the campuses of N.Y.U.’s far-flung “Global Networked University” — would stay there for a fee. The tower’s other half would offer rental housing for faculty, possibly with condo purchase opportunities. Davis explained that, for example, N.Y.U.’s Stern School of Business might want to buy a block of apartments in the building. Per city regulations, the hotel portion would have to offer basic hotel services, with a central switchboard and so forth.

To add the fourth tower to the Silver Towers complex, N.Y.U. also would need approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which landmarked the three buildings and their grounds in 2008.

If all goes according to plan, the university will make its application to L.P.C. this fall, and then, in 2011, would apply to City Planning for the rezoning as part of a general large-scale development plan.

On the other hand, if all of its plans are rejected, N.Y.U. would then focus on trying to develop on the current Morton Williams supermarket site at Bleecker St. and LaGuardia Place in 2021.

With reporting